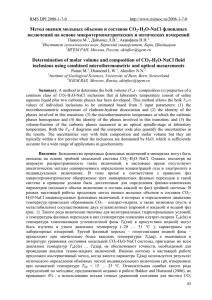

Master Thesis completed in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Master of Laws (LLM) in Environmental Law at Stockholm University, June 2013 Student Yenebilh Bantayehu Zena Student number 860625-T570 Title Enforcement under the Global Climate Regime: Reflections on the Design and Experience of the Kyoto-Marrakesh Compliance System Supervisor Jonas Ebbesson (Professor of Environmental Law) Length 19644 words of content (footnotes included) Acknowledgments My study at Stockholm University was simply impossible without the support of the Swedish Institute to which I am highly indebted for awarding me the Swedish Institute Study Scholarship. This thesis marks the zenith of a successful academic year I spent at the Faculty of Law in the Environmental Law Master Program. Having attended several seminars during the study, I remain thankful to the teachers and classmates for the inspiring discussions which have made me better as a student. I have specially enjoyed the thought provoking meetings with Professor Jonas Ebbesson who has made constructive comments on the draft works of this paper in his capacity of supervision. Finally I would like to extend my appreciation to my family and friends who have been my source of strength and perseverance despite being miles away. Table of Contents 1. Background on climate change and its regime................................................................................1 2. Purpose and Scope.............................................................................................................................2 3. Methodology.......................................................................................................................................4 4. Essence of Compliance in International Context............................................................................5 4.1. The Notion of Compliance and its distinction from related subjects...................................5 4.2. Compliance with International Law: A Brief on Theories..................................................7 5. Compliance in International Environmental Law..........................................................................9 5.1. Making MEAs Successful: Cooperation for Compliance or Invocation of State Responsibility?............................................................................................................................9 5.2. Place of Sanctions in MEA Compliance............................................................................11 5.3. From developing new MEAs to enforcing the existing ones.............................................12 5.4. UNEP and MEA Compliance............................................................................................13 6. The Kyoto-Marrakesh Compliance System..................................................................................14 6.1. Overview............................................................................................................................14 6.2. Negotiating the compliance procedures: From Buenos Aires to Marrakesh to COP/CMP.1..............................................................................................................................15 6.3. Adoption of the Compliance System: Available options and Challenges.........................16 6.4. The Compliance Committee..............................................................................................18 6.4.1. General Features................................................................................................18 6.4.2. The Facilitative Branch......................................................................................21 6.4.3. The Enforcement Branch...................................................................................24 6.5. Triggering Compliance Procedures...................................................................................27 6.5.1. Introduction........................................................................................................27 6.5.2. Self Triggering...................................................................................................28 6.5.3. Triggering by a party against another party's compliance.................................29 6.5.4. Triggering by regime bodies..............................................................................30 6.6. Fairness and due process in the Kyoto Compliance Procedures........................................32 6.7. Experiences with the Compliance Committee...................................................................34 6.7.1. Submission by South Africa: Putting the Facilitative Brach to a Test..............34 6.7.2. Cases before the Enforcement Branch...............................................................36 6.7.3. Concluding remarks on experiences of the enforcement branch......................41 7. Taking Stock: The Kyoto-Marrakesh Compliance System.........................................................42 7.1. Are the enforcement branch decisions enforceable?.........................................................42 7.2. Reflection on the legal value of consequences..................................................................43 9. Concluding Perspectives..................................................................................................................45 Index of Documents....................................................................................................................................48 Bibliography...............................................................................................................................................52 Acronyms CDM Clean Development Mechanism CITES Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora COP Conference of Parties COP/CMP Conference of Parties serving as Meeting of Parties ERT Expert Review Team GHG Green House Gas IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change ITL International Transaction Log KP-CP Kyoto Protocol Compliance Procedures MEA Multilateral Environmental Agreement MRV Measuring, Reporting and Verification UNEP United Nations Environmental Program UNFCCC United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Enforcement under the Global Climate Regime: Reflections on the Design and Experiences of the Kyoto-Marrakesh Compliance System 1. Background on climate change and its regime Excess GHG in the atmosphere as a result of fossil fuel powered civilization has wrecked the natural atmospheric balance causing the most notorious environmental problem of the contemporary worldclimate change. Science has established that human activities involving release of GHGs (particularly Carbon dioxide) take the blame for many of the maladies of unexpected climate change.1 The introduction of unwanted GHGs in to the atmosphere, having the effect of increasing the global temperature, impedes climate predictability threatening the ability of ecosystem to absorb (and adapt to) changes. It was, hence, evidently necessary to put in place a mechanism to slow down the pace of climate change and if possible restore the atmospheric balance. State sovereignty which is the underlying consideration in international law does not easily fit in to the governance of the atmosphere as the latter deals with volatile gases moving in disregard of state territory. Owing to its global scale and seemingly inseparable connection with economic independence, climate change poses unique challenge to development of a regime appealing to all states. Therefore, an international regime underscoring the indivisibility of global atmosphere and the common interest of states in its protection seems the only tenable approach to mitigate impacts of climate change. 2 The devastating effects of climate change garnered the attention of the international community which negotiated and adopted the UNFCCC in 1992.3 In an effort to achieve its overarching objective of stabilizing atmospheric GHG concentration4, the Kyoto Protocol was developed incorporating more robust and detailed commitments.5 Marking the pinnacle of international effort to mitigate effects of climate change, the Kyoto protocol imposes emission commitment for the convention's Annex I 1 Core Writing Team, Pachauri, R.K. & Reisinger, A.(eds.). Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report (IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland), at 37. 2 For legal status of the atmosphere see Birnie, P., Boyle, A., and Redgwell, C., International law & the Environment, Third edition (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2009) at 337. 3 http://unfccc.int/key_documents/the_convention/items/2853.php 4 UNFCCC, Article 2. 5 Protocol to the UNFCCC, Kyoto Protocol, adopted in COP 3 in Kyoto in 1997 and came in to force in 2005. 1 (developed) countries.6 These countries are accordingly subjected to obligations of limiting their emissions within their respective assigned amounts AND collectively reducing their emission by at least 5 per cent below the 1990 levels in the commitment period 2008 to 2012. 7 Article 10 of the protocol which precludes introduction of any new commitment for non Annex I countries has added fuel to the traditional north-south environmental dichotomy. Despite ongoing critics regarding its failure to induce meaningful participation of major emitters like the USA8 and China,9 the protocol not only survived for the first commitment period, but a second commitment period was agreed in COP 18 in 2012.10 2. Purpose and Scope As the Kyoto Protocol surges in to the second commitment period, growing attention is placed on adherence to the terms of the agreement. Bringing us to the subject of compliance, this study aims at examining the compliance system adopted by the protocol. With a contextual background in to the concept of compliance in international relations discourse, it looks up the development and features of compliance procedures in MEAs. With this foundation, the research continues to discussions on the more thematic and specific subject of examining the climate regime compliance procedure. It reviews the negotiation process of the compliance procedure, analyzes the organizational structure of the compliance committee, identifies the functions of its two branches, and examines the remedies applicable and their implication on propensity of states to comply. It is often submitted that the compliance system of the Kyoto Protocol is different from its counterparts in other MEAs. Checking the validity of such claims, the study aims at the following salient questions. What new contribution has the Kyoto Protocol compliance system brought to development of compliance in MEAs? 6 Note that the Annex I list is developed based on membership of political groups mainly the OECD. see: Depledge, J. "Continuing Kyoto: Extending Absolute Emission Caps to Developing Countries," in Baumert, K.A., Blanchard, O., Llosa, S., and Perkaus, J.F. Building on the Kyoto Protocol: Options to Protect the Climate (World Resources Institute, 2002l), pp 31-60, at 34. 7 Kyoto Protocol, Article 3 (1), supra note 5. 8 The US, although an Annex I country, is not subjected to binding emission commitment. "The Bryd-Hagel Resolution (1997)", unanimously passed by the US Senate and prevented the ratification of the Kyoto Protocol unless it included emission reduction commitments for developing countries. 9 Despite surpassing the US in Carbon dioxide emissions, China remains to be a non-Annex I country http://cdiac.ornl.gov/trends/emis/tre_tp20.html, http://unfccc.int/parties_and_observers/parties/annex_i/items/2774.php 10 Decision 1/CMP.8, "Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol Pursuant to its Article 3, paragraph 9, the Doha Amendment, (FCCC/KP/CMP/2012/13/Add.1, 28 February 2013), para 4. 2 Incorporating enforcement as its function, does the climate compliance mechanism offer strong procedural safeguards capable of enhancing credibility of the system? Are the practical experiences gained by the enforcement branch consistent with the mandate entrusted to it by the compliance procedures? Are there any loopholes within the Kyoto-Marrakesh compliance procedures? If yes, are they of such a magnitude to endanger the integrity and governance of the global climate regime? Although facilitation receives fair coverage, the discussion focuses on the quasi-judicial enforcement functions of the committee as this is acclaimed to be the flagship of climate compliance. A reflection on consideration of due process and fairness in the operations of compliance systems is tested against its impact on legitimacy of compliance decisions. A discussion on the road travelled so far reviews the practical experiences gained in both branches since 2006. Evaluations of the only case before the facilitative branch coupled with selected four cases handled by the enforcement branch illuminate the loopholes in the compliance system. Against these accounts; the study asks whether the mechanics employed by the compliance system have lived up to their promise of averting non-compliance. The study reflects up on the legal character of the compliance decisions. In concluding, it reaffirms that the compliance procedures of the Kyoto Protocol represents a new chapter in MEA compliance notion as it effectively introduced enforcement as an important function although suffering from absence of mechanism to enforce its important decisions. The present study remains short of analyzing trade measures as a component of enforcing compliance. The discussions in this study add to the existing knowledge on compliance in international environmental law. By explaining the mechanics of the dual approach adopted by the climate compliance mechanism, the study provokes further researches in to the prospect of such approach in the design of future MEAs. The reflection on the shift from facilitation to enforcement can be a starting point for compliance theorists to analyze its implications in the broader compliance and enforcement discourse. Particularly the relevance of the study goes to the climate governance in terms of conducting an up-to-date analysis of the experiences and the amplifying details that matter. In light of the new climate policy afoot, the study can be used as a summary from which detail analysis of the interaction between the compliance system and other mechanisms under the global climate policy can be launched. 3 3. Methodology Starting with the broader subject of compliance, the study delves in to specific and focused discussion on compliance of the climate regime. The first chapter outlines the notion of compliance in the international law raising critical concerns of dissecting compliance from related subjects and understanding the reasons behind state obedience to international law. In order to understand the motive behind adherence to international law, a trans-disciplinary approach relates international law to the philosophical theories advanced by international relations scholars. A review of the burgeoning literature in international relations discipline compares the major theories forwarded to explain the factors of compliance with international law. Having put the notion of compliance in context, a highlight of two broad approaches each arguing differently for an effective mechanism of promoting compliance will follow. With a juxtaposition of carrots and sticks, the entire study examines the extent of their application in MEAs and more particularly in the climate regime compliance system. Against the backdrop of compliance in MEAs, the study further narrows down to discuss the KyotoMarrakesh compliance system. Explanation of the negotiation process reviews the interaction among the successive COP/CMP decisions and outlines how the functionality of the compliance system transcends in to affecting the integrity of other regime setups; namely the flexibility mechanisms and the MRV responsibilities. For its core part of the discussion, the study relies on primary sources mainly in the form of decisions adopted under the Kyoto Protocol relating to establishment and functioning of the compliance system. While assessing the much hyped enforcement function of the climate compliance, four cases involving Greece, Canada, Croatia and Slovakia are discussed in fairly detailed manner as each of them have had profound importance in the functioning of the procedures. The analysis of these cases avoids thorough evaluation of the question of implementation as doing so invites examining the MRV rules of the protocol. Instead the intention is to check the competence of the compliance rules and identify its drawbacks revealed by the experiences. The remaining four cases (involving Bulgaria, Ukraine, Lithuania and Romania) are not covered in the study as their proceedings and outcomes did not pose a new challenge to the compliance system. With regard to the facilitative branch, the only significant experience gained until present time is covered in light of its contribution to the development of further compliance rules. The discussion on the consequences of non-compliance follows a law and economics approach as it demonstrates how law can interfere in to the economic benefits of a non-complying state. Where relevant the research adopts a comparison of specific components of the climate compliance system with the arrangements in other MEAs. 4 4. Essence of Compliance in International Context 4.1. The Notion of Compliance and its distinction from related subjects With the advent of a more interdependent world in the wake of the Cold War, international treaties covering socio-economic, political and environmental issues became significant components of the global governance. Whatever their objective, all international treaties share certain basic features. Aside from creating commitments to be fulfilled by their subjects i.e. usually states, international treaties are the foundations of cooperation among states to achieve a common goal. Realizing a common goal in international law provokes studying the interaction between the concepts of compliance, implementation, effectiveness and dispute settlement. Admittedly these concepts share common assumptions and at times seem to overlap. While this section does not seek to scrutinize every aspect of the relationship among them, it only delineates the underlying difference of compliance from the others. The following paragraphs define compliance and illustrate its distinction and relation to effectiveness, implementation and dispute settlement in international law. Defined as "the act or process of compelling compliance with a law, mandate, command, decree, or agreement "11, enforcement brings up the discussion of compliance to the surface. Despite perpetual lexical contest, compliance in this study is captured as "conformity of actor's (state in our case) behavior to treaty's explicit rules."12 It is imperative to note that the notion of compliance in this study shall be construed as compliance to explicit rules of the relevant regime. This is done intentionally to limit its scope excluding discussions on compliance to international customary rules. Effectiveness and Compliance Although very much related, compliance and effectiveness of a regime are distinct subjects. The notion of effectiveness seeks to discover the degree to which a treaty achieved its objective and thereby affected states behavior.13 Whether a regime is successful (as a whole) in terms of solving the problem it was created to address is at the heart of concept of effectiveness.14 For instance; a climate regime is created to mitigate the effects of climate change and restore the climate equilibrium. If the regime cannot bring about this desired result, it is ineffective despite the fact that states may have lived up to their emission reductions commitments prescribed by the regime. This would be the case if 11 Garner, B., Black's Law Dictionary, 9th edition (2009) at 608. Mitchell, R.B., International Oil Pollution at Sea: Environmental Policy and Treaty Compliance (Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 1994), at 30. 13 For insights in to concept of effectiveness see: Young, O.R., International Governance: Protecting the Environment in Stateless Society, (Cornell University, 1994) at 142-152. 14 Ibid. 12 5 the emission commitments embodied by the regime are easily achievable by states in the normal course of operations. Conversely, it is possible for a regime to be effective despite notoriously poor compliance record. In the earlier example, a climate regime with an ambitious target may be effective in restoring the climatic balance even when all the states have achieved only a minor portion of their emissions commitments. Therefore, effectiveness being the ultimate goal of any regime first of all requires creating obligations with capacity to compel states to change their behavior. These obligations should be incorporated in a legal structure to constitute a treaty. Only then can one validly discuss the notion of compliance which relates to enforcing the existing rules leaving out of its realm the question of whether or not such rules are apt to achieve the objectives of the regime. In the earlier example, compliance would relate to achieving the emission reduction commitment. Whether the fulfillment of these commitments will bring the restoration of climatic balance is not the scope of compliance. Thus far, it would be valid to conclude that high level of compliance, in as much as it may reflect an effective regime; it could also be an indication of poor legislation characterized by weak and shallow provisions falling short of inducing the desired behavioral change. Shallow and generic treaty provisions are easier to comply with while stringent and complex provisions tend to hamper compliance. Consequently compliance to treaty obligations partly depends on the textual architecture of the treaty. Implementation and Compliance Implementation of an international regime mainly relates to the process of putting the commitments in to practice.15 Essentially implementation has to do with all aspects of bringing commitments in to reality. Particularly it deals with designing and promulgating legislations (including enforcement clauses), constituting domestic and international institutions, determining their mandate and administering regime bodies. In the course of these processes, it is apparent to see that ensuring compliance is also considered as one objective of implementation. Nevertheless compliance can occur regardless of implementation in the sense that it is conceivable to be in compliance due to factors not related to implementation of an agreement. For instance; under the global climate regime, a party can be in compliance with emission reduction commitments due to a major economic collapse which brought its fossil fuel industries to their knees. Coincidental match state practice and requirements of a regime amounts to compliance but the state cannot be said to have implemented the regime. Thus 15 Raustiala, K. and Slaughter, A. "International Law, International Relations and Compliance" in Carlnaes, W., Risse, T., and Simmons, B. (eds), The Handbook of International Relations (Sage Publications Ltd, 2002), pp539-553, at 539. 6 implementation is conceptually neither necessary nor sufficient for compliance, although in practice it is often critical.16 Dispute Settlement and Compliance To a casual observer the notion of compliance may seem identical to dispute settlement. In general dispute settlement in international law confers states the right to protect their individual interest and thus builds upon adversarial structure where one state blames the other for interfering in the enjoyment of its rights. In contrast compliance procedures are particularly aimed at fostering the objectives of a treaty which represent common interest of parties. Hence a belief that the common interest of a treaty is endangered suffices to raise questions against a party with regard to its obligations. Compliance procedures draws upon a non-adversarial approach as the party who triggered the procedures usually remains in the background when the oversight body administers the question raised. However this does not mean the two concepts are exclusive of each other in MEAs.17 While all MEAs which have provided for compliance procedures also contain a dispute settlement clauses, they have also ascertained the independence of each other usually by providing a "without prejudice" clause in their compliance mechanisms.18 Be that as it may, the fact remains that the dispute settlement provisions of MEAs are not usually invoked and when invoked they are inefficient.19 4.2. Compliance with International Law: A Brief on Theories "Almost all nations observe almost all principles of international law and almost all of their obligations almost all of the time."20 Despite the lack of centralized enforcement mechanism, it appears perplexing to see that most international agreements are obeyed. Studies on the subject of compliance with international law have seen longstanding debate between theorists from international relations and international law discourses. A subject in the forefront of controversy relates to explaining why states, despite being the apex of public authority, would want to obey international law. A review of international relations literature suggests a spectrum of reasons in this respect. 16 Ibid. Treves, T., "The Settlement of Disputes and Non-Compliance Procedures", in Treves, T., Pineschi, L., Tanzi, A., Pitea, C., Ragni, C. and Jacur, F.R. (eds), Non-Compliance Procedures and Mechanisms and Effectiveness of International Environmental Agreements (T.M.C. Asser Press, The Hague, 2009), pp 499-518, at 517. 18 Ibid at 505. 19 Ibid at 517. 20 Henkin, L., How Nations Behave (Columbia University Press, 1979) at 47. 17 7 A realist point of view believes that states obey international law only in so far as it coincides with their national interest.21 Starting with a premise that the international system is anarchic with no governing body, realism asserts that pursuit of national interest is the only incentive that convinces states to accept (and comply with) an international commitment.22 As opposed to benevolent institutions; states are self-centered entities which invariably maneuver to hijack the international system to meet their national demands. The realists argue that international law will continue to be obeyed not because states fear consequences of violating the terms but because of a continued pursuit of national benefits in treaties.23 Therefore international law, according to realists, is a mere epiphenomenal coincidence of interests of states.24 The rational functionalism approach argues that states come in to international agreements to solve common problems they cannot solve unilaterally.25 Like the realists, they believe in the incentive of national interest to obey international laws. However functionalists do not stress the cynical character of states in international relations but contend that the international legal system is a collective good from which all states can reap benefit.26 For them international agreements are obeyed because they are built to be solutions for a common problem.27 They add that reputational concerns of states to prove their reliability and appear capable of living up to international mores are the main reasons why states want to obey international law.28 Others take international coercion as a compelling reason for states to discharge their international obligations. International coercion can take two forms; one in the form of punishments (sticks) for being in default of an international duty and another in the form of promises of reward for fulfillment of an international obligation (carrots). For others coercion from internal sources plays a significant role in inducing compliance to international agreements. 21 Simmons, B.A., "Compliance with International Agreements" (1998) 1 Annual Review of Political Science, 75 at 79. 22 Reus-Smit, C.(eds), The Politics of International Law (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004) at 1518. 23 Ibid. 24 Ibid. 25 Supra note 21, Simmons, at 80. 26 Ibid. 27 Ibid. 28 For an overview of reputation and compliance with international law, see: Guzman, A.T., How International Law Works: A Rational Choice Theory (Oxford University Press, New York, 2008) at 72-115. 8 Treaties create obligations that are expected to be obeyed by its parties. When all other components are robust, higher rate of compliance enhances the effectiveness of a regime which is why choosing the right approach to attain maximum compliance is taken seriously in the development of treaties. The scholarship of developing a strategy capable of inducing and maintaining higher compliance witnessed an ideological debate between the managerial approach and the sanction based (the enforcement) approach. Advanced by Abrham Chayes and Antonia H. Chayes in their book "the new Sovereignty", the earlier presupposes that states violate international law inadvertently due to factors such as ambiguity of the provisions or lack of capacity for performance29 and therefore cooperation to solve such causes is the right path towards enhancing compliance.30 In contrast; the sanction based thought asserts the necessity and importance of punishments for treaties that demand considerable departure of state behavior from what they would have done without the treaty.31 Arguing that measures creating costs for disobedience are better tools for effective compliance, they add the managerial approach fails to recognize contextual factors which may necessitate the use of sanctions or loss of benefits. Arguably both approaches have strong points and shortcomings. As we will see in the latter sections, applying one of them does not necessary require the exclusion of the other. 5. Compliance in International Environmental Law 5.1. Making MEAs Successful: Cooperation for Compliance or Invocation of State Responsibility? States conclude an international treaty with the hope of achieving some benefit. Ratification of a treaty is the most obvious mechanism of states declaring their consent to be bound by the terms of the agreement.32 Deviating from the terms of an international agreement constitutes breach of an international obligation and entails consequences under the laws of state responsibility.33 States alleging to have sustained injury due to an internationally wrongful act of another state can invoke state responsibility by virtue of which the offending state shall ensure cessation of the wrongful 29 Chayes, A. and Chayes, A.H., The New Sovereignty (Harvard University Press, 1995) at 9-17 ibid at 3. 31 Downs, G.W., Rocke, D.M., and Barsoom, P.N. "Is the Good News about Compliance Good News about Cooperation?" (1996) 50 International Organization, 379, at 383. 32 Hovi, J. and Halvorseen, A. "The nature, origin and impact of legally binding consequences: the case of the climate regime" (2006) 6 International Environmental Agreements, 157 at 163. 33 International Law commission (ILC) Draft articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts, 2001, Article 1. 30 9 conduct, provide assurances of non-repetition and make reparation for injury.34 Failure of the offending state to accord to these requirements entitles the injured party to take reprisal measure of ceasing performance of an international obligation owed to that state.35 Moreover, the law of treaties under the Vienna convention kicks in to allow termination or suspension of the treaty when the breach in question amounts to a 'material breach'.36 Essentially involving unilateral measures, this notion of state responsibility is the conventional enforcement mechanism under general international law. In respect of MEAs, the notion of state responsibility has been rarely used.37 Firstly invocation of state responsibility involves confrontation and adversarial practice making it far less interesting and sometimes futile for environmental treaties. The object of MEAs - protection of the environment does not square with confrontational enforcement mechanism. Confrontation degrades the spirit of cooperation and is practically a prelude to termination of diplomacy. In light of the precautionary approach which asserts for prompt preventive measures to avoid environmental degradation, cooperation rather than confrontation affords better protection to the environment. The precautionary approach heavily relies on collaboration of states in identifying and remedying an environmental problem. Secondly; in light of the fact that responsibility heavily relies on identifying a state in default of its international obligations, the inability of establishing a convincing causal link between a state's action (or omission) and damage for most environmental problems undercuts the effectiveness and desirability of unilateral enforcement. Finally cessation of performance of an international obligation owed to an offending state can be effective only against willful (intentional) breach of international duty. In contrary to this, non-compliance in MEAs can result from various non-intentional factors such as limitation of performance capacity. Supporting this assertion, the laws of state responsibility have envisioned a possibility of derogation where a special treaty rule is put in place to that effect.38 By interpretation this exception can be extended to the non-compliance mechanisms adopted by MEAs.39 The foregoing argument stands to serve that cooperation is the central tenet of compliance in MEAs. In general environmental treaties uphold non confrontational compliance systems embracing 34 Ibid, article 42 and article 48. Ibid, article 49. 36 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969, Article 60 (3). 37 Hovi and Halvorseen, Supra note 32. 38 ILC draft articles, article 55, supra note 33. 39 See generally: Pineschi, L., "Non-Compliance Procedures and the Law of State Responsibility" in Treves et al., supra note 17, pp 483-497. 35 10 international cooperation.40 Justification of the cooperative features of MEA compliance mechanisms is reflected in their meticulously formulated information gathering and reporting exercises which increase states' awareness of the objective of the treaty thereby boosting the propensity for a voluntary compliance and coordinated action.41 In these regards it would not appear farfetched to notice that MEAs square with the managerial view of rectifying non-compliance in non-adversarial manner. Putting so much importance on identification of the root cause of non-compliance as first adopted by the non-compliance procedure of the Montreal Protocol on Substance that Deplete the Ozone Layer (hereinafter called Montreal Protocol),42 Compliance procedures in MEAs take recognition of the respective situations of non-complying states. The compliance mechanisms of Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movement of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal (hereinafter called Basel Convention)43 and that of the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety44 have rehearsed the emphasis on identification of the causes of non-compliance on individual basis. Consistent to the hypothesis of managerial approach, promoting compliance in MEA draws upon states' bona fide intent of complying but for capacity reasons. This is one of the reasons why it is not uncommon to find MEAs in which a non-complying party can rely on the assistance of others to build up its capacity for enhanced compliance. 5.2. Place of Sanctions in MEA Compliance Appreciation of cooperative approach in compliance procedures of most MEAs does not necessary exclude application of "sticks" in the form of sanctions. Indeed most MEAs abstain from using the term "sanctions" when discussing non-compliance as negotiators remain wary of the power of sticks. Although numbered, there are MEAs whose compliance systems employ sanction. The 1973 CITES 40 Treves, T., "Non-Compliance Mechanisms in Environmental Agreements: The Research Method Adopted" in Treves et al., supra note 17, pp 1-10, at 2. 41 Brunnee, J. "Enforcement Mechanisms in International Law and International Environmental Law" in Beyerlin, U., Stoll, P.T., and Wolfrum R. (eds) Ensuring Compliance with Multilateral Environmental Agreements: A Dialogue between Practitioners and Academia (Brill Academic Publishers, 2006), pp.1-23 ,at 14-15. 42 Decision X/10, "Review of Non-Compliance Procedure" (UNEP/OzL.Pro.10/9, 3 December 1998), Annex II, para. 7(D), at 26. 43 Decision VI/12 "Establishment of Mechanism for Promoting Implementation and Compliance" Basel Convention Compliance Procedures, (Decisions adopted at the Sixth Meeting of the Parties to the Basel Convention, UNEP/CHW.6/40 10 February 2003). 44 BS-I/7, "Establishment of Procedures and Mechanisms on Compliance under the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety" Cartagena Protocol Compliance Procedures, (Report of the First Meeting of the Parties serving as the Meeting of the Parties to the Protocol on Biosafety, UNEP/CBD/BS/COP-MOP/1/15, 14 April 2004), Annex, Section III, 1 (a), at 99.. 11 has been exceptionally successful in enforcing compliance with a sanction based approach in the form of trade suspensions.45 Another prominent example is the compliance mechanism of Montreal Protocol which, under its article 8, refers to "treatment of parties found in non-compliance" and further, with its non-compliance procedure, introduces an "indicative list" of measures to cases of non-compliance.46 Observations of the practical experiences with compliance issues of the Montreal Protocol suggest growing cases of resorts to measures with more of a sanction and less of cooperation character.47 Shading light to the compliance system of the Kyoto Protocol, we can identify sanction oriented measures albeit presented in the form of requirement to participation in protocol's carbon mechanisms. These examples illustrate that sanctions are not totally evil to MEA compliance systems. When combined with elaborate measures of facilitation and cooperation, sticks can, in fact, be conducive to deter non-compliance. A sound conclusion from the preceding paragraphs will be that adoption of a cooperative (managerial) approach or enforcement approach in MEA compliance systems does not follow any common standard. Prima facie all environmental treaties advocate for cooperation and assistance among parties for enhanced compliance and implementation. However, history and experience dictate that mere assertion of cooperation is inadequate to ensure effective compliance. Thus punitive measures are increasingly finding crucial importance in many MEA compliance systems. Factors, including but not limited to specific problem for which the MEA is established, its level of seriousness and the financial capacity of parties play the decisive role in determining the blending of sanctions amidst cooperation in compliance systems of MEAs. Ergo the two approaches do not necessarily exclude each other in their appearance; instead they can be used together to develop effective compliance mechanism. 5.3. From developing new MEAs to enforcing the existing ones The propagation of MEAs in the past decades failed, in many cases, to ensure that the environment is protected in a sufficient manner. Such proliferation carries with it a room for equivalent increase in 45 For a review of success of sanctions in compliance history of CITES see: Sand, P.H. "Sanctions in case of Non-Compliance and State Responsibility: Pacta sunt servanda - Or Else?" in Beyerlin et al., supra note 41, pp.259-271. 46 Decision IV/5 "Non-compliance Procedure" Montreal Protocol Non-Compliance Procedures, para 3; Annex V (Report of the Fourth Meeting of the Parties to the Montreal Protocol, UNEP/OzL.Pro.4/15, 25 November 1992). 47 For overview of practice of the non-compliance procedure of the Montreal Protocol, see generally: Victor, D.G. "The Operation and Effectiveness of the Montreal Protocol’s Non-Compliance" in Victor D.G., Raustiala, K. and Skolnikoff, B.E. (eds), Implementation and Effectiveness of International Environmental Commitments: Theory and Practice (International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, 1998), pp 137-177. 12 cases of non-compliance thus undermining the very essence of developing the MEAs. With the help of non-state observers exposing cases of non-compliance and the academia delivering articulated analysis of compliance theories, the international community is conferring equal importance to enforcement of the existing MEAs. As a reflection of the growing importance attached to compliance, regional organizations began to take up the duty of development of compliance guidelines. Most notably, the UNECE enacted the "Guidelines for Strengthening Compliance with and Implementation of multilateral environmental agreements in the ECE Region"48. While such organizations are aimed at promoting compliance of MEAs with high relevance to the regional interest, MEA secretariats, often drawing their mandate from their COPs, are also increasingly engaging in promoting compliance of their respective MEA. Aside from the scattered efforts by MEA secretariats and regional organizations to enhance compliance, there was a need for a concerted global approach which would uphold states' common interest in the environment. Among other objectives, this broader approach would emphasize assisting developing countries and economies in transition enhance their capacity to improve compliance records and appreciate participating in MEAs. 5.4. UNEP and MEA Compliance Suffice to note that UNEP, for most of its life time since its establishment in 1972, has been burdened with development of MEAs, one may argue that there was a blatant disregard to development in compliance and enforcement aspects of the existing MEAs. Increasing awareness on compliance loopholes underscored that enforcing the existing MEAs as opposed to formulating new ones is the pressing issue if the environment was to be protected sufficiently. Hence compliance and enforcement of MEAs were brought to the UNEP work structure. Perhaps the milestone, in this regard, has been the development and adoption of "Draft Guidelines for Compliance with and Enforcement of multilateral environmental agreements" by the Governing Council of the UNEP in 2002.49 Supplemented by a detailed manual50 and thus recommended for use by MEA secretariats and regional organizations, the guidelines seek to identify common grounds for non-compliance and offer recommendations on how to alleviate them. Unlike the specific approach followed by compliance efforts of regional organizations or MEA secretariats, UNEP guidelines 48 ECE/CEP/107. http://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/env/documents/2003/ece/cep/ece.cep.107.e.pdf, last accesses, 20 May 2013. 49 UNEP/GCSS.VII/4/Add.2, http://www.unep.org/GC/GCSS-VII/default.asp, last accessed, 20May, 2013. 50 http://www.unep.org/delc/portals/119/UNEP_Manual.pdf, last accessed, 20May, 2013. 13 exhort a holistic approach toward enhancing compliance in a broader sense making them adaptable and relevant to virtually all MEAs regardless of difference in objective and regional interest. Although non-binding, these guidelines play a vital role in directing governments, MEA secretariats, NGOs and regional institutions towards a coordinated approach for better compliance. As such they put importance on co-ordination among states and international organizations for creation of strong institutional capacity. With such a jump start, the UNEP continued to engage in a series of activities, inter alia, disseminating the guidelines to stakeholders, strengthening the capacity of developing countries, convening a series of regional workshops to gather comments and reviewing and testing the guidelines in several MEAs.51 Being the melting pot of compliance systems of all MEAs, the UNEP guidelines aspire to serve as foundation for future MEAs as well. 6. The Kyoto-Marrakesh Compliance System 6.1. Overview The current climate regime has grown in its sophistication to include a range of legal arrangements targeting emission reductions. In this section we concert our discussion on the procedures and mechanisms put in place to ensure compliance with the obligations of the Kyoto Protocol. The importance of compliance with the commitments of the Kyoto Protocol cannot be overemphasized as even in the best scenario of 100 per cent achievement of the emission targets, climate change will probably continue to take its toll. Unique features of the climate regime present unique challenges to compliance theories and rules. Most importantly; Kyoto Protocol cuts deep across the economic policy of states for emission reduction commitments involve altering the conduct and behavior of private enterprises that hold vital place in sustaining economic security of states. Compliance with the Kyoto commitments was certain to catalyze changes in the economic policy of states and thus the process of developing compliance mechanisms was exhausting and at times frustrating too. The Kyoto-Marrakesh compliance system is built on three pillars of operation. First there is the enabling clause under article 18 of the protocol which states "The Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to this Protocol shall, at its first session, approve appropriate and effective procedures and mechanisms to determine and to address cases of non-compliance with the provisions of this Protocol, including through the development of an indicative list of consequences, taking into account the cause, type, degree and frequency of non- 51 For a review of the activities see: Mrema, E.M., "Cross-Cutting Issues to Ensuring Compliance with MEAs" in Treves et al., supra note 17, pp.201-229 at 221-226. 14 compliance. Any procedures and mechanisms under this Article entailing binding consequences shall be adopted by means of an amendment to this Protocol." As per this provision, the first COP/CMP adopted the compliance procedures and established the compliance committee marking a second pillar of the compliance mechanism. The committee is composed of a plenary, a bureau, the facilitative branch and the enforcement branch. Thirdly, the compliance committee developed detailed rules of procedure to govern the procedural routines of its operation. Unlike other MEAs, the role of COP/CMP is marginal in the functioning of the KyotoMarrakesh compliance procedures. Instead the compliance system significantly relies on findings and opinions of team of experts coordinated by the secretariat pursuant to article 8 (2) of the protocol. Although falling within the structure of the MRV rules and thus not part of the compliance committee per se, these expert review teams (ERTs) hold an indispensable role in the compliance system. Starting with the negotiation process, the following sections discuss these components and working structure in a considerable detail. 6.2. Negotiating the Compliance Procedures: From Buenos Aires to Marrakesh to COP/CMP.1 Negotiating a competent compliance system for the Kyoto obligations was one of the difficult tasks faced by negotiators. The adoption of the Buenos Aires Program of Action in COP-4 heralded the commencement of official work on the development of compliance mechanisms.52 Setting the motion in such a way a Joint Working Group (JWG) was thereby established with a prior objective of developing procedures by which compliance with the commitments of the protocol were to be ensured.53 Starting with the identification of compliance related issues of the protocol; the JWG proceeded with the development of substantive and procedural elements of the compliance system. Parties soon began to hand in successive submissions54 wherein they reasoned the objective of the planned compliance system and defined their propositions on several practical details. Just as the other aspects of the climate regime, development of the compliance system enjoyed sheer scale of divergence of interests and stances. Among other areas, intense negotiations ensued regarding mandate of the enforcement branch (whether to empower it with compliance issues of limitation of 52 Decision 1/CP.4., "The Buenos Aires Plan of Action" (FCCC/CP/1998/16/Add.1, 25 January 1999), at 4. Decision 8/CP.4 "Preparations for the first session of the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol: matters related to decision 1/CP.3, paragraph 6", Annex I and II (FCCC/CP/1998/16/Add.1, 25 January 1999). 54 FCCC/SB/1999/MISC.4, 29 April 1999; FCCC/SB/1999/MISC.12, 22 September 1999; and FCCC/SB/2000/MISC.2. 11 May 2000. 53 15 emissions only or to include reduction commitments too), capacity to trigger the compliance system, the legal character of consequences of non-compliance and mode of adoption of the compliance mechanisms. The struggle of reconciling these differences partly contributed to the creation of innovative strategies which altogether made the final output an advanced legal arrangement in contrast to previous MEA compliance procedures. Surviving all the seemingly irreconcilable negotiation differences was also an indication that the regime was even more resilient than what was originally thought.55 In the year 2000 COP-6, held at The Hague, saw a near collapse of the climate regime with the suspension of talks due to opposing positions on issues of contribution of carbon sinks and use of flexibility mechanisms. In the wake of The Hague trauma, the second part of COP-6 adopted the Bonn agreement which picked up the pieces to seal a political deal on climate compliance regime.56Most of the features and rules of the incumbent compliance system were agreed upon during the Bonn agreement but were not structured in a legal text format. The commencement of COP-7 in 2001 in Marrakesh ascertained that agreement over most of the controversial issues was achieved but for the mode of adoption and the legal implications of the consequences. The COP-7 decided to adopt the legal text containing the procedures and mechanisms relating to compliance of the Kyoto Protocol and recommended the first COP/CMP to adopt these procedures.57 Failing to agree, COP-7 upheld the decision to defer the mode of adoption talks to the first COP/CMP. Based on this recommendation the first COP/CMP adopted the compliance procedures in 2005 as finalized and formulated in a legal language in Marrakesh.58 The introduction of the compliance procedures marked a milestone in the governance of the entire climate regime and heralded a new entrant to the list of compliance mechanisms of MEAs. 6.3. Adoption of the Compliance System: Available options and Challenges As the first COP/CMP was approaching, it became obvious that mode of adoption was going to be a major agenda for the meeting. Drawing the attention of negotiators, the available options for adoption 55 Brunnee, J., "COPing with Consent: Law Making Under Multilateral Environmental Agreements." (2002) 15 Leiden Journal of International Law, 1 at 4. 56 Decision 5/CP.6, "The Bonn Agreements on the implementation of the Buenos Aires Plan of Action" Annex, section VIII (FCCC/CP/2001/5, 25 September 2001) at 48. 57 Decision 24/CP.7, "Procedures and Mechanisms relating to Compliance under the Kyoto Protocol", FCCC/CP/2001/13/Add.3. (21 January 2002) para 1 and 2,at 64. 58 Kyoto Protocol Compliance Procedures (KP-CP): Decision 27/CMP.1, ‘Procedures and Mechanisms Relating to Compliance under the Kyoto Protocol’, Annex, FCCC/KP/CMP/2005/8/Add.3, 30 March 2006, at 92 16 were receiving meticulous examination. This was mainly because the choice of mode of adoption entailed certain ramifications with a potential to spill over to other components of the compliance system which may ultimately alter the key elements of Kyoto commitments. A point in case; eligibility to participate in the Kyoto flexibility mechanisms is tied to methodological and reporting requirements under Article 5 (1) and (2), and Article 7 (1) and (4) of the Protocol. As illustrated in the following paragraphs, this interplay of the compliance system and the flexibility mechanisms of the protocol results in different outcomes depending on the mode of adoption of the compliance procedures. As the preamble of Kyoto-Marrakesh Compliance Procedures declared, the COP/CMP has the prerogative of determining the legal form of the compliance procedures.59 Apparently this prerogative has never been put in to action thus leaving the concern over the legally binding nature of the compliance procedures unresolved and open for debate. Adopting the compliance procedures by a COP/CMP decision was the first option. One should, however, check whether decisions of COP/CMP are binding legal instruments on parties. Noting that the protocol does not make an explicit provision for binding nature of COP/CMP decisions, it would appear that decisions are not legally binding instruments per se. Notwithstanding that, decisions are political agreements with a character of imposing de facto control on the positions and behaviors of states and hence viewed as binding enactments.60 Therefore the eventual effect of adopting the compliance procedures by a COP/CMP decision would mean that all parties would be subject to the compliance rules and procedures.61 This option then seems to favor fairness as it treats all states equally under one decision. The interaction between compliance procedures and flexibility mechanisms would, therefore, be less complicated as all states accept the compliance procedures through the mechanism of the decision adopting it. Leaving no state outside the realm of the compliance procedure, this approach ensures fairness to all parties as regards eligibility of flexibility mechanisms. Amendment of the protocol was the second option for adoption of the compliance procedures. The rules of amending the protocol emphasize agreement by consensus; in unison recognize the possibility 59 KP-CP preamble, Ibid, See generally: Lefeber, R. "From the Hague to Boon to Marrakesh and Beyond: A Negotiating History of the Compliance Regime under the Kyoto Protocol" in Hague Book of International Law (Kluwer Law International, the Hague, 2001) at 25-54. 61 Ibid. 60 17 of differences by allowing for adoption by the three-fourth majority vote.62 Assuming that a proposal for an amendment garners the required 75 % vote, the rule of enforcement dictates that the amended part of the protocol will be effective only on the parties that have accepted the amendment.63 It follows that an amendment for adoption of the compliance procedures will only be effective against the parties who have explicitly accepted the amendment proposal. The possibility to decline from accepting the amendment proposed for adoption of the compliance procedures means that the flexibility mechanisms are available for the only Kyoto parties which have accepted the amendment. Hence giving unequal opportunity for fulfilling emissions commitments, the amendment oriented approach upsets the entire playground of climate obligations. The time consuming nature of an amendment process presents yet another challenge. Entry in to force of an amendment relies on securing acceptance by at least three-fourth of the Kyoto parties.64 In practice, this implies parliaments and congresses of the parties will have to ratify the amendment and this will take substantial amount of time thereby delaying the entry in to force of the compliance system. Therefore, an amendment procedure for adoption of the compliance procedures is flawed with inherent challenges related to lack of striking proper balance and timeliness. In theory adoption by an amendment can be preferable over adoption by a decision as the earlier is always legally binding with enforcement consequences. However the improbability of achieving a consensus and protracted process of entry in to force render the amendment route less meritorious to the effective enforcement of the compliance mechanisms. The last sentence of article 18 of the protocol which reads "Any procedures and mechanisms under this Article entailing binding consequences shall be adopted by means of an amendment to this Protocol ." seems to suggest a middle way in which the procedures entailing soft consequences do not need amendment while those involving harder sanctions should undergo the amendment procedure. The discussion on the legal character of the consequences in the latter section elaborates more on this. 6.4. The Compliance Committee 6.4.1. General Features Central to the climate regime compliance procedure is the compliance committee shouldering the task of facilitating, promoting and enforcing compliance with the commitments of the protocol. 62 Kyoto Protocol, Article 20 (3), supra note 5. Kyoto Protocol, Article 20 (3), para 4 and para 5, supra note 5. 64 ibid 63 18 Establishing a committee composed of four functional arms namely; the plenary, the bureau, the facilitative branch and the enforcement branch65, the Kyoto compliance procedure is the first of its kind to combine facilitation and enforcement functions within the same committee.66 Due to the administrative nature of their functions, this study does not seek to examine the plenary and the bureau segments of the committee. Despite the differences in their mandate and functions, the two branches are urged to cooperate in their operations whenever situations so demand.67 Cooperation in the two branches merits betterment of compliance records especially in cases where the regimes of facilitation and enforcement overlap. For example, when states are heading to failure of submission of annual inventories, they can request for advice and facilitation while at the same time having to deal with risk of triggering the enforcement arm for non-compliance. Individual cases of non-compliance are handled by one of the two branches as per the allocation made by the bureau in accordance with their respective mandates.68 While the facilitative branch can deal with questions of implementation relating to all parties, the enforcement branch handles questions of implementation pertaining to the commitments of Annex I countries. The branches do not make individual reports to the COP/CMP as all activities of the committee including list of decisions taken are reported to through the plenary.69 One striking difference of the Kyoto compliance committee from those of other MEAs can be found in the decision making mandate of the committee. In many cases the mandate of MEA compliance committees goes only as far as identifying and investigating cases of alleged non-compliance and reporting the findings to the supervising body (usually the COP/MOP). In numbered instances as in the case of the Montreal Protocol, such functions can include making appropriate recommendations. 70 A little advanced mandate can be found in the Aarhus convention (on access to information, public participation and access to justice in environmental matters) compliance procedure which vests upon the committee the authority to adopt measures of facilitative nature as long as cooperation and agreement from the non-complying party can be secured.71 In general it is submitted that the ultimate 65 KP-CP, section II (2), supra note 58, at 93. Brunnee, J., "The Kyoto Protocol: A Testing Ground for Compliance Theories?" Heidelberg Journal of International Law (2003) 255 at 256. 67 KP-CP, section II (7), supra note 58, at 93. 68 KP-CP, section VII (1), supra note 58, at 97. 69 KP-CP, section III (2), a, supra note 58, at 94 70 Montreal Protocol Compliance Non-Procedure, para 9, supra note 46, at 45. 71 Decision I/7; "Review of Compliance", (ECE/MP.PP/2/Add.8, "Report of the First Meeting of the Parties to the Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-making and Access to Justice in 66 19 power of deciding whether a party is in non-compliance or not is bestowed upon meeting of parties of respective MEAs. With unequivocal empowerment of the enforcement branch to issue declarations of non-compliance, the Kyoto compliance procedure introduced a new chapter as regards the power of compliance committee.72 As the enforcement branch de jure holds a decision making power, the role of the COP/CMP is, accordingly confined to reviewing appeals against the decisions of the enforcement branch and that too is only possible for cases of denial of due process.73 It is interesting to notice that in case the COP/CMP agrees with at least three quarters majority to override the adopted decision, it can only refer the case back to the enforcement branch for re-evaluation meaning that it cannot proceed to conclude that the decision was wrong and the subject party is in compliance. On membership matters, history of development of MEA compliance systems confirms that the members of the committee are usually representatives of the member states. This shall not, however, be construed to imply the non-existence of compliance committees whose members are selected in their personal capacity. Following the footsteps of compliance procedures of the Aarhus Convention, the Barcelona Convention (on Protection of the Mediterranean Sea) and the Cartagena Protocol (on Biosafety to the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity), members of the compliance committee of the Kyoto Protocol are selected in their individual capacity with a recognized competence relating to climate change.74 In all other compliance committees including those composed of members in individual capacity, the important question of declaring the non-compliance of a party was invariably the mandate of the governing body (usually COP/CMP) of the regime. Hence the loophole in such compliance systems appears conspicuous in the fact that decisions in the oversight body take cognizance of multitude of factors than just findings and recommendations of the committee. In as much as governing bodies of MEAs try to harmonize their decision with the recommendations of their compliance committees, the fact that recommendations can be set aside remains a challenge for non-compliance governance in MEAs. While the assertion of composing compliance committees with individuals of technical expertise rather than state affiliation existed before the birth of the Kyoto-Marrakesh compliance system, the novelty in latter comes in its extensive effort of minimizing political intervention (depoliticizing compliance). The Kyoto Protocol compliance procedure indeed pioneers the concept Environmental Matters; Aarhus Convention Compliance Procedures, 2004), Section XI Consideration by the Compliance Committee.. 72 KP-CP, section XV, supra note 58, at 102. 73 KP-CP, section XI (1), supra note 58, at 100. 74 KP-CP, section II (6), supra note 58, at 93. 20 of constituting a compliance committee with individuals of purely technical orientation while simultaneously empowering it to issue declarations of non-compliance. With such an orthodox arrangement the negotiators have sought to maintain a politics free environment in the operations of the compliance committee. Contributing for the robust functioning of the committee, such combination puts the Kyoto-Marrakesh compliance system a stride ahead of its predecessors in terms of affording better procedural guarantees for effective compliance and protecting states against politically motivated decisions. 6.4.2. The Facilitative Branch Guiding states to achieve maximum attainable environmentally friendly behavior is the prior objective of any MEA compliance procedure. In contrast to notion of asserting strict compliance to commitments, facilitation presents itself as a better vehicle to achieve environmental friendly behavior of states. Facilitation in the form of guaranteeing financial, technical and institutional assistance enhances confidence of parties in the regime, demonstrates that commitments are attainable and lays foundation for introduction of further commitments. This was the context in which the facilitative branch of the Kyoto compliance committee was incorporated. Although the introduction of the enforcement branch seemed to have downplayed the traditional role of facilitation, the facilitative branch continues to play an indispensible role in maintaining the overall integrity of the climate regime. Functions The leading agenda behind the facilitative branch is provision of advice and facilitation to the parties in implementing the protocol and promotion of compliance by parties with their commitments under the protocol.75 As the Kyoto Protocol has drawn an almost universal ratification with 192 members, 76 the disparity in the economic and political conditions of parties is quite staggering thus presenting yet another challenge to the governance of the climate regime. It is, therefore, valid that the causes and circumstances of each non-compliance question are the reflections of the political and economic make-up of the state in question. Seen in light of subjectivity of non-compliance issues, the futility of generic and one-for-all type of facilitation mechanisms appears a self answered question. To this end, facilitation tasks by this team of ten individuals77 takes consideration of the principle of common but 75 KP-CP, section IV (4), supra note 58, at 95. Status of Ratification of the Kyoto Protocol: http://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol/status_of_ratification/items/2613.php, last accessed, 20 May, 2013. 77 KP-CP, section II (3), supra note 58. 76 21 differentiated responsibilities, respective capabilities within Annex I countries and the circumstances pertaining to the question before it78. This degree of flexibility reflected in the functions of the facilitative branch agrees with the managerial approach of emphasizing on identification of the cause of noncompliance and remedying it with incentives rather than penalty. Narrowing down we find that advice and facilitation concerns regarding the fulfillment of commitments under article 3 (1) of the protocol falls within the mandate of this branch until the end of the first commitment period.79 Even though the first commitment period started only in 2008, the very complex nature of limiting and reducing emissions made it necessary to start acting long before 2008 in order to meet the targets for the commitment period. The work of facilitative branch therefore started before the start of the first commitment period in the form of assisting countries in their effort to set themselves in the right direction towards achieving emission commitments. Prior to the commencement of the first commitment period, it had to assist Annex I parties in their effort to establish a national system for the estimation of anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of all greenhouse gases not controlled by the Montreal Protocol.80 Now that we are at a turning point with the coming to an end of the first commitment period, it is worth noting that Annex I parties can no more avail themselves of the services of the facilitative branch regarding their substantive emission commitments. The facilitative branch reaches out to the least developed countries, the small islands and those countries prone to impacts of climate change by handling questions related to their protection against adverse social, environmental and economic effects that may result from actions of Annex I countries trying to fulfill their emissions commitments.81 With respect to developing countries hosting CDM projects, the functions of the facilitative branch in building their capacity and smoothening transfer of technology will have particular importance for fulfilling their reporting duties. With the protocol's flexibility mechanisms, the facilitative branch shall handle questions related to provision of information as to whether an Annex I party is using these mechanisms as supplemental to domestic actions.82 In determining whether Annex I parties are on the right track towards achieving their substantive emission target, the virtue of article 3 (2) of the protocol required them to have made 78 KP-CP, section IV (4), supra note 58. KP-CP, section IV (6), a, supra note 58. 80 KP-CP, section IV, 6(b), supra note 58; Kyoto Protocol, article 5(1), supra note 5. 81 KP-CP, section IV, 5(a), supra note 58; Kyoto Protocol Article 3(14), supra note 5; UNFCCC, Article 4 (8),(9), supra note 4. 82 KP-CP, section IV 5(6), supra note 58; Kyoto Protocol, article 6, article 12 and article 17, supra note 5. 79 22 "demonstrable" progress by 2005. While the facilitative branch was required to consider reports made in this regard, the negotiators have not defined the meaning of "demonstrable." With no quantified benchmark above which an accomplishment was to be accepted as "demonstrable," article 3 (2) of the protocol could hardly be regarded as anything more than an exhortation. Consequences Section XIV of decision 27/CMP.1 states: "The facilitative branch, taking into account the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, shall decide on the application of one or more of the following consequences: a) Provision of advice and facilitation of assistance to individual Parties regarding the implementation of the Protocol; b) Facilitation of financial and technical assistance to any Party concerned, including technology transfer and capacity building from sources other than those established under the Convention and the Protocol for the developing countries; c) Facilitation of financial and technical assistance, including technology transfer and capacity building, taking into account Article 4, paragraphs 3, 4 and 5, of the Convention; and d) Formulation of recommendations to the Party concerned, taking into account Article 4, paragraph 7, of the Convention. Emanating from its very nature of facilitation, the consequences at the disposal of this branch are all 'soft' measures taking the form and combination of advice, consultation, financial assistance and facilitation of technological transfer. Here again, stress is added to the need of applying the measures bespoke to the specific character of the question of implementation at hand. The importance of taking consideration of the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capacities of states is reinforced to ensure the active engagement of parties and encourage them to seek advices and assistance instead of refraining from active involvement. The use of the phrase "one or more" in defining the consequences serves to show the wide margin of discretion the branch holds in deciding which consequences to apply. Mirroring the managerial approach, the measures employable by this branch presuppose the full willingness of parties to comply and attribute non-compliance to factors such as lack of capacity. Allowing parties to open up regarding their achievements, plans and actions, the softness of these measures ensures a non-confrontational operating environment. The favorable conditions of facilitation are aimed at attracting states to avail themselves and make use of the resources of the branch to achieve their emission targets. The propensity to comply is strengthened with a message signaling the abundance of assistance as opposed to measures penalizing noncompliance. 23 6.4.3. The Enforcement Branch While it is in the interest of the convention and the protocol that all parties fulfill their obligations assisted by facilitation and advice from the facilitative branch, it was, nevertheless, imperative to constitute the enforcement branch with a prior duty of deterring non-compliance. Just as the facilitative branch, this branch is also composed of ten individuals the selection of whom reflects a balance between Annex I countries, non Annex I countries and regional representation.83 This is subject to the exception that all members of the enforcement branch shall have a legal experience at the time of election.84 Consistent with the function of determining cases of non-compliance, the condition of legal expertise required of all members was intentionally left broad to allow non lawyers with sufficient legal experience to serve as members.85 Consequently it can be inferred that negotiators, in as much as they wanted to provide ample facilitation towards enhanced compliance, they were also determined to ensure that non-compliant behaviors were met with punitive measures. Function Championed as game changer in MEA compliance systems, the enforcement function of the climate compliance procedure represents a quasi-judicial arrangement with obligation of objectively assessing cases and issues decisions. As such the functions of the enforcement branch relates to non-compliance with procedural obligations and non-compliance with substantive obligations. As the nature of the obligations at stake differs in these two areas, so do the measures available to rectify them. The functions of the enforcement branch, as listed under section V (4) of the compliance procedures, are hereafter analyzed based according to the nature of the obligations in questions. The enforcement branch shall be responsible for determining whether an Annex I party is not in compliance with its quantified emission limitation or reduction commitments as per article 3 (1) of the protocol.86 This provision is not as straightforward as it initially appears. Although nothing is stipulated as to time when this function is ripe, other procedural rules of the protocol confirm that this substantive function shall remain only in papers until the formal closure of the first commitment period. Impliedly this relieves the states of any legal consequence related to the substantive obligations prior and during the first commitment period as the important question of whether states 83 Kp-CP, section V (1), supra note 58, at 95. KP-CP, section V (3), supra note 58, at 96. 85 Ulfstein, G. and Werksman, J., "The Kyoto Compliance System: Towards Hard Enforcement" in Stokke, O.S., Hovi J., and Ulfstein, G. (eds) Implementing the Climate Regime: International Compliance, (Earthscan and International Institute for Environment and Development, UK 2005), pp.39-62 at 47. 86 KP-CP, section V (4) (a), Supra note 58, at 96. 84 24 have accomplished their emission commitments is only to be entertained when the first commitment period comes to an end. In theory end of 2012 marks the end of the first commitment period; nevertheless connecting the dots in the reporting and accounting rules of the protocol make it clear that compliance assessment for this period is not due until 2015.87 Hence the function of the enforcement branch in respect of determining non-compliance of an Annex I party with its emission commitments under article 3(1) of the protocol is practically inactive at the time of writing. Another major function of the enforcement branch is determining non-compliance with methodological and reporting responsibilities of Annex I countries. 88 As prescribed in article 5 (1), (2), and article7 (1) and (4) of the protocol, these duties mainly relate to establishment of national systems, methodological requirements of estimation, preparation of an annual inventory (reporting requirements) and requirements concerning the modalities for accounting of assigned emission amounts. Understandably these requirements carry heavy weight for the success of the protocol and were thus supplemented with elaborate procedures adopted by the first session of COP/CMP. A detail discussion in to the working mechanics of these responsibilities escapes the scope of this study. However a point should be made that these rigorous procedures subject the Annex I countries to extra economic and political pressure. A strong incentive was therefore needed to offset the cumbersomeness of these procedures. This was the rationale behind linking participation in the flexibility mechanisms and compliance with measuring and reporting duties.89 The idea is that the prospect of economic benefit that can be accrued from involving in the flexibility mechanisms ensures that parties comply with the methodological requirements. In effect this arrangement is designed to send a message that the integrity of the flexibility mechanisms depends on the integrity of the compliance system; not to mention that it was also a persuasion mechanism to attract more Annex I countries to accept and ratify the compliance procedures if they be adopted by means of amendment.90 Thus the enforcement branch bears the responsibility of policing the continued observation of these responsibilities as a precondition for participation the flexibility mechanisms. 87 See mainly Decision 13/CMP.1, "Modalities for the accounting of assigned amounts under Article 7, paragraph 4, of the Kyoto Protocol" and Decision 15/CMP.1 "Guidelines for the preparation of the information required under Article 7 of the Kyoto Protocol" (FCCC/KP/CMP/2005/8/Add.2, 30 March 2006). 88 KP-CP, section V (4) (b), supra note 58 at 96. 89 Decision 2/CMP.1 "Principles Nature and Scope of Mechanisms Pursuant to Article 6, 12 and 17 of the Kyoto Protocol", (FCCC/KP/CMP/2005/8/Add.1, 30 March 2006), para 5,at 4. 90 Ulfstein and Werksman, supra note 85. 25 While determination of non-compliance with procedural or substantive obligations remains its major function, the enforcement branch also assumes a different kind of responsibility in the form of resolving conflicts between the independent verification bodies called the ERTs (section 6.5.4 on page 30) and a party under assessment. Accordingly it passes judgments over the necessity of adjustments and corrections recommended by ERTs where these have been contested by the party under assessment.91 These added mandates vested in the enforcement branch substantiate the claim that the COP/CMP is highly marginalized in the operations of compliance procedures and consolidating the enthusiasm of minimizing political interferences. Consequences92 Table 1 Consequences under the enforcement branch Non-compliance with regard to Applicable Consequences the methodological and reporting duties under article 5 (1), (2) and article (1), (4) of the protocol. the eligibility requirements for the flexibility mechanisms the quantified emission limitation and reduction duties under article 3 (1) of the protocol Declaration of non-compliance Order the party to develop a plan which shall include analysis of the grounds of non-compliance, measures intended to rectify the non-compliance and a schedule of implementation Suspension of eligibility until reinstated as per section X of decision 27/CMP.1. Deduction from the party's assigned amount for the second commitment period of a number of tonnes equal to 1.3 times the amount in tonnes of excess emissions Order the party to develop a compliance action plan identifying the causes of non-compliance and presenting a plan of tackling it. Suspension from international emissions trading until reinstated as per section X (3) or (4) of decision 27/CMP.1. As straightforward as it is put, the objective of the consequences for infringement of the methodological and reporting duties is to bring the party back to compliance. Bearing in mind that access to the flexibility mechanisms is the convincing factor for the Annex I countries to subject themselves to the meticulousness of the reporting rules, one could argue that the consequences provided in this category lack the strength to bring the party in to compliance. Section 6.7 in the later pages consolidates this assertion by comparing the consequences of non compliance with 91 92 KP-CP, section V (5) (a) and (b), supra note 58, at 96. KP-CP, section XV, supra note 58, at 102. 26 methodological and reporting duties with the consequences of non-compliance with eligibility requirements for the flexibility mechanisms. With regard to the flexibility mechanisms, a party shall initially prove to the satisfaction of the enforcement branch that it meets all the eligibility requirements for participation; only then it will be permitted to make use of the flexibility mechanisms. An initial admission to the flexibility mechanisms is, nonetheless, no guarantee for an indefinite participation. Continued participation in the flexibility mechanisms is rather contingent upon continued fulfillment of the eligibility requirements. When the enforcement branch has found that a party no more meets the requirements for participation, it shall suspend the participation privilege of the party. Consistent with the nature of these consequences being hard with a potential to end up sanctioning a party, table 1 above shows that the enforcement branch shall apply a set of predefined consequences for corresponding non-compliance cases. By ensuring that a certain consequence shall be triggered automatically due to a breach of a corresponding obligation, negotiators have minimized the discretion of the enforcement branch. Automaticity of consequences under the enforcement branch is thus seen as a decisive factor to deliver objectivity, enhance legal certainty and increase legitimacy of the procedure.93 Looking at compliance cases handled by the enforcement branch, section 6.6 reveals that the practice may have deviated from the consequence rules to a certain extent. 6.5. Triggering Compliance Procedures 6.5.1. Introduction As compliance procedures in MEAs are developed to address cases of non-compliance, the first step in the process is naturally bringing the issue to the attention of the body with the oversight of handling such concerns. Informing the compliance body about a possible breach of an obligation triggers a compliance mechanism. Granted that filing for cases of non-compliance is a highly delicate concern with a potential to be easily associated with political motive, it is no surprise that negotiation of MEAs generally devotes substantial time and energy to develop rules of triggering compliance procedures. Central to the issue of triggering rests the question of entitlement to launch the compliance procedure. In general the rules of triggering so far negotiated within MEA compliance systems envisage mainly two possibilities in this respect; self triggering and triggering by a party in 93 Mehling, M., "Enforcing Compliance in an Evolving Climate Change" in Brunnee, J., Doelle., M. and Rajamani, L. (eds), Promoting Compliance in an Evolving Climate Change, (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2012), pp. 194-216 at 204. 27 respect of another party's compliance. Moreover few MEA compliance systems such as that of the Aarhus Convention have gone further bestowing triggering right to other persons including NGOs.94 Providing for the rules of triggering in section VI of decision 27/CMP.1, the Kyoto-Marrakesh compliance procedures has in theory envisaged three major triggering mechanisms; the self trigger, party to party trigger and triggering by special regime bodies called Expert Review Teams (ERTs). Each option is further discussed below. 6.5.2. Self Triggering Squaring with the notion of cooperation and facilitation embedded in MEA compliance procedures, self triggering allows a party to set in motion the compliance system against itself. A reflection of the managerial approach; this mechanism is put in place to assist parties who have failed to comply despite a bona fide effort to that effect. Most compliance procedures of MEAs incorporate a clause for self triggering. To mention but a few, the Aarhus Convention, the Basel Convention, the Cartagena Protocol and the Montreal Protocol all contain provisions for self triggering. 95 Self triggering is a mechanism of building confidence of the parties and encouraging them to approach the respective compliance bodies and seek assistance whether financial or technical. The Aarhus Convention Compliance Procedures furthered this effort of encouragement by providing for confidentiality of information provided by a party in respect of its own compliance.96 As the mechanism of self trigger is devised with the presumption that states retain bona fide intention of complying, it accepts all parties requesting facilities and financial assistance. Hence the prospect of some states availing themselves of these assistances without actually doing their due diligence to comply with their obligations can be an apparent pitfall of self triggering mechanisms. The Kyoto-Marrakesh compliance mechanism acknowledges self triggering by enabling a state to launch a question of implementation with respect to itself.97 Naturally self triggering fits only with the facilitative branch for states will not approach the committee to inform they have failed with the commitments falling under the mandate of the enforcement branch as doing so would put them at the risk of harder consequences. Unfortunately no Kyoto party has ever moved to utilize this mechanism to date. 94 Aarhus Convention Compliance Procedures, para 18, supra note 71. Aarhus Convention Compliance Procedures, para 16, supra note 71; Basel Convention Compliance Procedures, para 9 (a), supra note 43, at 47; Cartagena Protocol Compliance Procedures, section IV, 1 (a), supra note 44, at 99; Montreal Protocol Non-Compliance Procedure, para 4, at 44, supra note 46. 96 Aarhus Convention Compliance Procedures, para 28, supra note 71. 97 KP-CP, section VI (1) (a), supra note 58, at 96. 95 28 6.5.3. Triggering by a party against another party's compliance A common denominator of all MEA compliance mechanisms is that they all envisage a possibility for a state to launch a non-compliance case against another state.98 As readily available it is, questioning another state with respect to discharging its obligations in a specific MEA is not, however, something states are eager to indulge in to mainly for two reasons. First and foremost, it is often quite difficult for a state to be aware of the compliance details of another state. This lack of information on the compliance records of another state is subject to the exception where the non-compliance by a state has direct impact on the triggering state. Environmental problems exhibiting stronger causal link enable a party to stay abreast of the compliance records of other states. For instance, under the 1997 Convention on the Law of the Non-navigational Uses of International Watercourses, failure of a party to maintain the amount and quality of the water is directly felt in a riparian party. Secondly party to party triggering, to a certain extent, exhibits an adversarial character which impairs inter-state diplomatic relation putting a strain on the essence and integrity of MEAs. Hence this procedure is not frequently used.99 A rather interesting point in a party to party triggering is whether all states can avail themselves of it. This issue is best understood from an angle of the nature of the obligation created by the respective MEAs. Although MEAs dealing with transboundary environmental issues may have a global dimension, they tend to create bilateral obligations the violations of which by a party have specific impact in the interest of the other. The Basel Convention Compliance Procedures exemplify this by qualifying party to party triggering by the requisite of establishing the existence of a specific interest at stake due to non-compliance by another state.100 It further adds that the party must have been directly involved with the allegedly non complying party.101 Similar provisions can be found in the other MEAs as well. On the other hand MEAs dealing with global concerns have universal dimension as their prior objective is the protection of humanity in general. The titanic task of achieving such objectives entails a collective response and deep cooperation of virtually all states which is why the obligations created by these MEAs are construed to be owed to everyone. The Montreal Protocol and the global climate regime are the most significant examples of these MEAs creating erga omnes obligations. Non- 98 Jacur, F.R., "Triggering Non-Compliance Procedures" in Non-Compliance Procedure and Mechanisms, in Treves et al., supra note 17, pp.373-288, at 375. 99 Ibid. 100 Basel Convention Compliance Procedures, para 9 (b) and para 10, Supra note 43. 101 Idem. 29 compliance by a party in these regimes does not result in any single party being specifically (separately) affected; it rather affects the international community thus justifying why all states should be allowed to launch application for compliance. In respect of the climate regime, the rules of triggering the compliance procedures generally reflect the underlying feature that states have shared responsibility towards mitigation of impacts of climate change. Climate responsibilities constitute an erga omnes obligation the violation of which can be questioned by all states on behalf of the international community. Thus entitlement to submission of question of implementation should not be attached to a condition of demonstrating a specific interest at stake because of non-compliance of another state. It in this spirit that, under section VI (1), 'b' of decision 27/CMP.1, the KyotoMarrakesh compliance mechanism entitles any party to submit a question of implementation. However it is important to note that the party triggering the compliance procedures against another party does not take up the role of a compliant; it only turns the compliance ignition on while leaving the remaining duty of investigating the details to the committee. 6.5.4. Triggering by regime bodies Although not popular, MEA secretariats and compliance committees sometimes trigger questions of compliance.102 The rationale behind enabling these organs relates to the fact that they are usually encountered with information about the compliance records of parties. It is believed that capacitating them to trigger compliance procedures gives an extra incentive to closely investigate the information they receive from parties. In respect of the Kyoto-Marrakesh compliance system, ERTs are the major organs belonging to this group of triggering mechanism. The prerogative of ERTs to launch a question of implementation, as discussed in the following section, finds support in their mandate of verifying the information submitted by parties. Expert review teams (ERTs) As we have seen above non-compliance issues before the end of the first commitment period is related to procedural inventory requirements. The complexity in the calculation and reporting mechanism has called for the necessity of establishing independent bodies of experts with the capacity to verify the validity of the information submitted by parties. Not a component of the compliance committee per se, yet an integral part of the compliance procedure, the expert review teams (ERTs) are established as per article 8 (2) of the protocol and 102 Jacur, supra note 98. 30 governed by a detailed regulation under the Marrakesh accords.103 Their role in the compliance procedure kicks in with the receipt of information from each Annex I country regarding its methodological and reporting duties under the protocol. As the name implies, these teams are tasked with the duty of conducting technical assessment of all aspects of implementation of commitments and identification of factors and influences with a potential to hamper compliance to commitments.104 When, in the process, the ERTs identify potential problems, they are expected to wear a facilitation hat and inform the party of the problems and offer advice on how to correct them. 105 Coming as an additional force to the facilitative branch; the work of the ERTs contributes substantially to promoting compliance. If and when the party declines to implement the advices and recommendations of ERTs that are of mandatory nature to fulfillment of its commitments, the ERTs become agents for launching a question of implementation.106 However their mandate does not include issuing pronouncement of non-compliance; nor do they prosecute the case once the compliance procedures are launched. As observed in the experiences gained so far, ERTs assumed greater role than the facilitative branch as the latter not only cannot launch a question of implementation but was also relatively less active during the years of operation. Practically ERTs are the ultimate bodies with access to detail information as to how a party is performing in respect to its reporting duties which is possibly why most of the decisions of the compliance committee are based on the reports of ERTs. Given such institutional setup and mandate, it is a natural consequence that an ERT report is the major factor triggering non-compliance procedure. In the later chapter when discussing the experiences with the enforcement branch, we find that all questions of implementation handled by this branch were launched as a result of ERT reports. If there is anything this arrangement and experiences can tell us, it is the fact that proper functioning of ERTs is an essential ingredient for proper functioning of the compliance system. Therefore it is of a particular interest that the ERTs operate in an impartial manner and in politically free working environment. In this respect, the members of ERTs are selected in their individual capacity and shall at all times in their duty reflect professional competence and refrain from politically motivated judgments107. Nonetheless, contrary to the enforcement branch, the ERTs are established by the 103 Decision 22/CMP.1 "Guidelines for Review under article 8 of the Kyoto Protocol", ERT rules (FCCC/KP/CMP/2005/8/Add.3, 30 March 2006) at 51. 104 Kyoto Protocol , Article 8 (3), supra note 5. 105 ERT rules, para 7, supra note 103, at 53. 106 ERT rules, para 8, supra note 103, at 53. 107 ERT rules, section E, para 20-35, supra note 103. 31 apolitical secretariat giving an extra incentive to the impartiality and minimized political interference.108. 6.6. Fairness and Due process in the Kyoto Compliance Procedures State sovereignty remains a major factor for weak enforcement of international law. In the face of the fact that it is seldom possible to force a state to comply with a decision against it, providing for a fair treatment in the decision making process is crucial to maintain international order. Ensuring due process in the context of any compliance system in MEAs is primarily a mechanism of consolidating the legitimacy of institutional and procedural setups of the system. Due process comes as a tool of striking balance between effectiveness and fairness of any compliance mechanism. 109 Perhaps deliverance of due process and procedural fairness in determination of non-compliance is the only possible way to maintain integrity of a regime; especially when it deals with common concern as in the case of climate change. As such, due process touches upon various aspects of institutional and procedural dynamics of a given compliance system. Even-handedness of a compliance procedure is for example reflected in the effort of creating geographical balance in the membership of compliance bodies.110 Legitimacy of decisions of non-compliance is better argued for when a sense of representation of the states in the decision making bodies is reflected. Another important aspect of due process, especially in regimes asserting for sanctions for non-compliance, is the right of the non complying party to be heard and present its views on compliance question lodged. Free flow of information in the compliance procedure, publication of decisions and other facets of transparency increase the confidence of states in the compliance procedure. In the Kyoto-Marrakesh compliance negotiations, delivering due process was the common position of all negotiators. However disagreements arose when pinning down to development of a strategy which warrants optimal fairness especially in the operations of the enforcement branch. Some states particularly the US argued that the cause of due process is better served by providing a definite set of consequences for breach of certain well defined obligations.111 This approach envisages that the compliance body would have little or no discretion in its operations as violation of a given commitment is automatically met with a given consequence. It was more than obvious that this 108 Kyoto Protocol, Article 8 (2), supra note5. Ulfstein and Werksman, supra note 85, at 40. 110 Ibid. 111 Ibid at 41. 109 32 approach of automaticity puts the negotiators on extra burden of formulating detailed rules defining with utmost precision which consequences would be triggered by which infringements. Others particularly the European delegation contended that non-compliance cases should be handled on an individual basis (case by case approach) and due process would then be achieved by allowing a significant margin of discretion for the determining body.112 Arguing that fairness requires flexibility within a certain margin, this approach relied on the assumption that it would be impossible and naive to foresee every detail of non-compliance and design a thorough list of consequences at the outset. As we have seen earlier the final outcome of such negotiation has struck balance in affording substantial margin of flexibility and discretion to the facilitative branch; in unison reflecting automaticity in the enforcement branch. In the Kyoto-Marrakesh compliance mechanism due process and fairness kicks in as soon as the procedures are triggered with a submission as per section V of decision 27/CMP.1. A submission from any eligible applicant shall conform to the specifications prescribed under section 10 of the compliance committee rules of procedure.113 Upon confirming that the question of implementation fulfills the minimum standards, the bureau decides which branch the case should be forwarded to. 114 The branch receiving the case then makes a preliminary assessment in which it examines whether the allegation is backed by sufficient information, is not de minimis or ill founded and is based on the requirements of the protocol.115 These requirements are of course of no relevance for a self triggered question as the intention here is to provide procedural guarantee against maneuvers to attack a party under the pretext of non-compliance. Before proceeding to the merits of the case, both branches shall be convinced that the question of implementation does not suffer from insufficiency of information and that it is not motivated by factors unrelated to the protcol's obligations. Within the context of the enforcement branch these preconditions can be compared to the notion of presumption of innocence until proven guilty in criminal proceedings in so far as they are required to provide protection to the accused party. A decision to continue to the merits of the question of implementation before the enforcement branch confirms that the case exhibits factual and/or legal basis for non-compliance; 112 Ibid. Decision 4/CMP.2 "Compliance Committee" Rules of Procedure (FCCC/KP/CMP/2006/10/Add.1, 2 March 2007) at 23. 114 Ibid, rule 19. 115 KP-CP, section VII (2), supra note 58, 97. 113 33 suggesting that the burden of establishing a prima facie case lies with the ERT or the party making the allegations.116 Other attributes of due process and transparency are found in requirements of various time limits in the entire process, the duty to communicate the preliminary findings to the party concerned, provisions for designation of the party during various stages, the opportunity for the party to present its views on the case, and the possibility to appeal against decisions of enforcement branch for denial of due process.117 Apparently the general procedures to be employed during evaluation of merits of the case reflect the passion of negotiators to escort the journey of non-compliance determination with notions of transparency and fairness. The Emphasis added to the effort of adopting compliance decisions by consensus seem to suggest a reference to another pillar of criminal proceedings - proof of guilt beyond reasonable doubt as opposed to preponderance of evidences.118 Failing unanimity, the double majority voting requirement (majority from Annex I AND majority from non Annex I) for adoption of any decision of the enforcement branch kicks in.119 In a way, this gives an added value to the notion of due process by ensuring that decisions against Annex I countries necessarily involve support of Annex I representatives in the enforcement branch. By virtue of such rule, the possibility of politically motivated decision against an Annex I country seems halted. This procedural safeguard affords protection to Annex I countries in two phases; one during the preliminary session when a decision whether or not to investigate the merits is discussed and another when a final decision on declaration of non-compliance is considered. Undoubtedly the above elements play decisive role in continued confidence of parties in the compliance procedures; not to mention their initial role in providing fertile grounds for adoption of the entire compliance procedure as part of the Kyoto governance. 6.7. Experiences with the Compliance Committee 6.7.1. Submission by South Africa: Putting the Facilitative Brach to Test A striking experience in respect of the facilitative branch relates to its failure to agree on how to address the submission made by South Africa on behalf of the G77 and China with regard to Annex I countries who had not submitted their report demonstrating their progress towards their commitment 116 Ulfstein and Werksman, supra note 85, at 53. See generally KP-CP, section VII, section IX, section XI, supra note 58. 118 Ulfstein and Werksman, supra note 85, at 53. 119 KP-CP, section II (9), supra note 56. 117 34 under article 3 (1) of the protocol.120 The submission made in a letter format did not enumerate the countries to which it was referring to. It was rather drafted in such a way as to refer to any Annex I party who had not submitted its report in due time. As there were 15 Annex I countries who had not submitted their reports by the time the submission was made, the question of implementation targeted these countries. Underlining late report filing, the letter reiterated the facilitative branch should check if such failure can be considered as an early warning to a potential non-compliance with the emission commitments.121The facilitative branch was not able to make a deliberation of preliminary examination within the specified time and stated the same in its report to the plenary of the compliance committee.122 Whether or not to proceed with the case became a questioned entangled in three core issues which brought acute division between the members. Firstly there was concern on the acceptability of a submission which does not make an exhaustive list of the countries in respect of which the question was raised. The second division relates to whether a submission by a party on behalf of a group was legit. Finally the matter of supporting the question with corroborated information proved to be another bone of contention. Granted that the submission rules under section VI of decision 27/CMP.1 do not give clear answer on these issues, the facilitative branch descended in to an impasse which undermined its capacity and credibility of the committee. This incident brought to light an important loophole in the compliance procedure and had a direct impact on development of further rules of procedure of the compliance committee which, among other things, specified minimum standards for admissibility of submissions.123 Reassuring that a stalemate of such kind will not be repeated, these rules on the procedures of the compliance committee have made their presence felt in the subsequent decisions most of which were adopted by a consensus.124 120 CC-2006-1-1/FB, A letter to the Chairman of the Compliance Committee: "Compliance with Article 3.1 of the Kyoto Protocol" (2006). 121 Ibid. 122 CC-2006-1-2/FB , "Report to the Compliance Committee on the Deliberations in the Facilitative Branch Relating to the Submission Entitled “Compliance with Article 3.1 of the Kyoto Protocol” (CC-2006-1/FB to CC-2006-15/FB)", para 5. 123 Rules of Procedure, supra note 113. 124 Oberthur, S and Lefeber R., "The Experience of the First Five Years of the Kyoto Protocol’s Compliance System" in Couzens, E., and Honkonen, T. (eds) International Environmental Law Making and Diplomacy Overview 2012 (University of Eastern Finland, Finland, 2011 ) pp.65-92, at 71. 35 In the above particular case, the branch dropped the question relating to Latvia and Slovenia as both countries managed to file their report by the time the submission was considered. 125 Regarding the remaining thirteen states, the facilitative branch finally decided not to proceed with the merits of the question justifying that the submission requirements are not fully complied with. 6.7.2. Cases before the Enforcement Branch As far as the enforcement branch is concerned, it has dealt with eight questions of implementation involving Greece, Canada, Croatia, Bulgaria, Romania, Ukraine, Lithuania and Slovakia.126 The following section examines four cases involving Greece, Canada, Croatia and Slovakia selected to have had a relatively significant role in testing the modus operandi of the enforcement branch. The other four cases were more or less in line with the compliance procedures having little impact in challenging the functioning of the branch. Greece127 Following the initial report filed by Greece, ERT review was conducted on the information contained in the report and other information secured during and after an in-country check up of the national systems. The outcome of the review revealed that the country is not fully complying with the guidelines for national systems of GHG estimations under Article 5 (1) of the Kyoto Protocol and the guidelines for the preparation of the information required under Article 7 of the Kyoto Protocol.128Thus the compliance procedure was triggered with the submission by the ERT. The allocation to the enforcement branch was accordingly made by the bureau. Having ascertained that the question meets the preliminary requirements of the compliance procedure, the enforcement branch adopted a unanimous decision to proceed with the merits of the case.129 In the following months, a series of steps ensued according to compliance procedures. Among others; a communication regarding the decision to proceed was made to Greece which requested a hearing and made a written submission (6 February 2008), an expert advice was requested by and delivered to the branch. A pronouncement of non-compliance at a hearing of the enforcement branch in March 2008 was then 125 CC-2006-8-3/Latvia/FB," Preliminary Examination: Party concerned, Latvia"; CC-2006-14-2/Slovenia/FB, "Preliminary Examination: Party concerned, Slovenia", 21 June 2006. 126 http://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol/compliance/items/2875.php 127 CC-2007-1/Greece/EB, "Question of Implementation-Greece", http://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol/compliance/enforcement_branch/items/5455.php 128 CC-2007-1-1/Greece/EB, "Report of the review of the initial report of Greece: note by the secretariat ",8 January 2008, para 244, at 57. 129 CC-2007-1-2/Greece/EB, "Decision on Preliminary Examinination: Party concerned; Greece, 22 January 2008, para 6. 36 followed by another submission from Greece. A final hearing (17 April 2008) cemented the decision of non-compliance and underlined that Greece is not eligible to participate in the Kyoto mechanisms.130 With that followed the procedure for application of consequences for non-compliance as per section XV of decision 27/CMP.1.131 Accordingly Greece submitted a plan explaining how it intends to restore compliance only to receive a request from the enforcement branch to submit a revised plan. With the submission of the revised plan came a request for reinstatement of eligibility for the flexibility mechanisms. Following the findings of the ERT confirming that the national systems for estimation are working as intended and that Greece has the capacity to effectively handle inventory issues, the enforcement branch adopted a decision (13 November 2008) in which it stated that the question of implementation with respect to Greece's eligibility no longer exists and declared therein the country is fully eligible to participate in the carbon mechanisms.132 Offering a real opportunity for testing the mechanics of the enforcement branch, the case of Greece set an important precedent for subsequent questions of implementation. The procedures provided for determination of non-compliance and application of consequences proved to be effective in general sense. This represented an important step in compliance philosophy of MEAs as it proved enforcement entailing application of sticks can indeed be an appropriate mechanism to deter noncomplying behavior. Canada133 Canada saw the enforcement branch for alleged non-compliance regarding the status of its national registry necessary to keep track of transfer of emission units. Here again an ERT finding that the national registry of Canada is out of tune with the requirement of article 7 of the protocol triggered the case. With a decision to proceed the enforcement branch made a communication to Canada who did acknowledge delay in establishing national registry and further requested a hearing which was held on 14 and 15 of June 2008. In this hearing Canada demonstrated that it had addressed the question citing its national registry was already in place and operational as per article 7 of the protocol. The 130 CC-2007-1-8/Greece/EB, "Final Decision: Party concerned; Greece", 17 April 2008, para 17. Ibid, para 18. 132 CC-2007-1-13/Greece/EB, "Decision under Paragraph 2 of Section X: Party concerned; Greece, 13 November 2008, para 13. 133 CC-2008-1/Canada/EB, "Question of Implementation-Canada", http://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol/compliance/enforcement_branch/items/5298.php 131 37 enforcement branch then decided not to proceed any further with the question of implementation while it reiterated previous non-compliance.134 Admittedly the procedure in the present case did not vary much from the case involving Greece. However an important peculiarity of this case concerns the statement of Canada's previous noncompliance in the final decision of the branch.135 One can ask whether this was a right procedure or the enforcement branch should have omitted this and found that Canada was in compliance.136 Although not expressly provided for in the compliance procedures, mentioning past non-compliance in a decision not to proceed and thus bringing this fact to the public is arguably justified in light of deterring subsequent non-compliance.137 An interesting point is the fact that Canada remedied its noncompliance (with regard to this specific question of implementation) in due time despite its public statement that it did not intend to meet its emission targets.138 Drawing upon the rationalist theory on compliance of states, a possible reason for this could be the shaming effect of being declared a noncomplying party which undermines the reputation of the government both domestically and internationally. Croatia139 Like the previous cases, the question of implementation against Croatia came from the report of ERT which found that the country has added 3.5 megatonnes of CO2 eq to its assigned amount violating Article 3 (7) and (8) and the modalities for the accounting of assigned amounts under Article 7 (4) of the protocol. Croatia did not contest the fact of adding to its assigned amount, however, argued that it, being a country in transition to market economy, is allowed to do so by virtue of decision7/CP.12 under the convention which allows certain flexibility for economies in transition. The core of the issue was thus whether this flexibility would extend to modifying the assigned amounts of emission commitments of countries. While the enforcement branch determined Croatia to be in non-compliance and suspended it from Kyoto mechanisms140, this case stands out for being the first in which the 134 CC-2008-1-6/Canada/EB, "Decision not to Proceed Further: Party concerned; Canada", 15 June 2008, para 18. 135 Ibid ,para 17. 136 Doelle, M., "Experience with the facilitative and enforcement branches of the Kyoto compliance system" in Brunnee et al., supra note 93, pp 102-12,1at 114. 137 Ibid. 138 Ibid. 139 CC-2009-1/Croatia/EB, "Question of Implementation-Croatia", http://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol/compliance/enforcement_branch/items/5456.php 140 CC-2009-1-8/Croatia/EB, "Final Decision: Party concerned; Croatia", 26 November 2009, para 22 and 23. 38 appeal provision under section XI of decision 27/CMP.1 was invoked. In its appeal against the final decision, Croatia vehemently argued that the decision was inappropriate and inequitable further mentioning inconsistency with Article 31 (1) , (2) and (3), 'b' of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties which captures the good faith interpretation rule of a treaty.141 Another concern of importance is that Croatia declared that it did not intend to submit a plan while its appeal was pending before the COP/CMP thus triggering the compliance rule which asserts that the decisions of the enforcement branch shall be valid and standing until a decision on the appeal is adopted.142 The enforcement branch agreed to bring this fact to the attention of the COP/CMP as the compliance procedures did not provide for mechanisms for enforcing a decision of the enforcement branch. The sixth COP/CMP held in Cancun considered the appeal but was not able to make deliberations and postponed it for the seventh COP/CMP. On August 2011, Croatia withdrew its appeal adding it had developed a different understanding of the calculation of its assigned amounts and submitted successive plans to remedy the non-compliance. During its 18th meeting in February 2012 the enforcement branch concluded that there no longer continued to be a question of implementation and Croatia was accordingly reinstated in to being eligible to participate in the mechanisms.143 Although Croatia had withdrawn its appeal, it would have been interesting to see whether the appeal would be acceptable. From a legal perspective, this would have opened a new chapter in which the COP/CMP adopts a decision which will either override the decision of the enforcement branch and refer it back for reassessment or confirm the final decision. First and foremost, there is a question if the COP/CMP limits the scope of the appeal strictly to the conditions stipulated in the compliance procedures or if it opens up to other arguments embodied in the appeal particularly the relation between the climate regime and the law of treaties under the Vienna convention. On the narrower approach, the compliance procedure appeal provision has made it clear that appeal is allowed against decisions relating to article 3 (1) of the protocol and only for denial of due process. Hence a point of departure should be ascertaining whether the proceeding held against Croatia was related to commitments of limitation and reduction of emissions. This would probably be answered in the negative as the issue was over discrepancy between Croatia and ERT over calculation of assigned amounts. However; deciding whether due process has been denied may turn out to be a complex 141 FCCC/KP/CMP/2010/2, "Appeal by Croatia against a final decision of the EB of the Compliance Committee”, 19 February 2010. 142 KP-CP, section XI (4), supra note 58. 143 CC-2009-1-14/Croatia/EB, "Decision under Paragraph 2 of Section X: Party concerned; Croatia, 18 February 2012, para 12. 39 question as it seeks to identify precisely which procedures in the compliance system are regarded as elements of due process and which of these are alleged to have been denied. Accordingly these steps involve a great deal of discretion making sure that the final outcome was far from certain. Seeing how developments would have unfolded in COP/CMP would have given a landmark experience to the compliance procedures. Slovakia144 The case of Solvakia is the most recent question of implementation which was triggered as a result of a review of the 2011 annual report submitted by the country which found that the information contained in the report did not comply with the requirements of article 5 (1) of the protocol further mentioning that the national system of Slovakia did not fully perform the functions set out in decision 19/CMP.1.145 The new experience in this proceeding was that the ERT calculated and applied nine adjustments to the inventories following identification of underestimation of emission estimates. Slovakia disagreed with the adjustments and forwarded the disagreement to the enforcement branch thereby initiating a function of the branch which had not been put to test in the previous proceedings. Pursuant to section V (5) of the compliance procedures, the branch adopted a decision on whether to apply adjustments on Slovakia's inventories under article 5(2) of the protocol.146 Prior to the decision, Slovakia had accepted some adjustments which were taken note of in the decision and regarding the others the decision favored Slovakia by making a statement that the adjustments were no longer necessary.147 A final decision on the question was adopted on 17 August 2012 basically confirming the preliminary finding adopted on 14 July 2012. Hence Slovakia was found to be in non-compliance with the guidelines for national systems for the estimation of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions by sources and removals by sinks under article 5(1) protocol.148 At the time of writing Slovakia has made two successive submissions explaining its plans and reporting the progress achieved. A striking difference from the previous cases is found in this decision. Although the case related to national registry requirements and the eligibility for Kyoto mechanism, the final decision adopted underscored, in unequivocal manner, that the non-compliance due to partial operational impairment of 144 CC-2012-1/Slovakia/EB, "Question of Implementation-Slovakia", http://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol/compliance/questions_of_implementation/items/6920.php 145 FCCC/ARR/2011/SVK, " Report of the individual review of the annual submission of Slovakia submitted in 2011", 17 May 2012, para 238, at 83. 146 CC-2012-1-6/Slovakia/EB, " Decision on a Disagreement whether to apply Adjustments to Inventories under Article 5, Paragraph 2, of the Kyoto Protocol: Party concerned: Slovakia", 14 July 2012. 147 Ibid. 148 CC-2012-1-9/Slovakia/EB, " Final Decision: Party concerned; Slovakia", 17 August 2012.Section III. 40 Slovakia's national system does not relate to the eligibility requirements.149 Hence Slovakia remains eligible for the carbon mechanisms. To this effect the consequences stated in the decision made an apparent omission of suspension of eligibility.150 In all the previous questions of implementation, determination of non-compliance with the requirements of article 5 (1), (2) and article 7(1), (4) of the protocol and the relevant decisions adopted thereunder had invariably led to suspension of eligibility for participation in the flexibility mechanism. This decision serves to illustrate exceptional cases wherein declaration of non-compliance with the reporting and methodological requirements may be met with subsequent plans for rectifying the non-compliance while remaining eligible for the flexibility mechanisms. Understanding the reason behind the exceptionality in this case, however, calls for a detailed analysis of the various decisions adopted regarding the reporting and methodological commitments and finding the fine line making such difference. Apparently this falls outside the bounds of the present study. The following section makes a conclusion of these experiences with reference to the provisions of the compliance procedures. 6.7.3. Concluding remarks on Experiences of the Enforcement Branch Recalling that the compliance system stipulated three different kinds of consequences to be applied by the enforcement branch (table 1 above) depending on the kind of obligation in question, this section makes a summary of how far this distinction has been followed during the practical cases discussed in the forgoing section. The consequences to be applied for non-compliance with the methodological and reporting duties are different from the consequences applicable for failing to meet the eligibility requirements. But what are the requirements of eligibility to the flexibility mechanisms? The first session of COP/CMP established that eligibility to participate in the mechanisms by a Party included in Annex I shall be dependent on compliance with methodological and reporting requirements under Article 5, (1), (2), and Article 7,(1), (4) of the Kyoto Protocol.151 It is interesting to note that these are the very same obligations whose non-compliance faces a declaration of non-compliance and an order of development of plan to address the violation. Does this mean non-compliance with the methodological and reporting duties leads to an automatic loss of privilege for participation in the flexibility mechanisms? If the answer turns in the affirmative, the next issue of reinstating the eligibility could face two routes. The first would be through the procedure for reinstatement which 149 Ibid, para 24, at 8. Ibid, para 30 at 9. 151 Decision 2/CMP.1, para 5, supra note 89. 150 41 shall result in reinstatement of the party when the enforcement branch is convinced that the grounds for the suspension have ceased to exist.152 This procedure of reinstatement is initiated by the party itself and potentially involves the scrutiny of the ERT making it demanding for the party to prove its assertion of reinstatement. This is true because the enforcement branch heavily relies on the information and findings of the ERT. The second route will be to follow the rectification of noncompliance procedures under section XV (1) to (3) of decision 27/CMP.1. Successful adherence to these procedures brings the party to compliance one more time. Hence the party starts to fulfill the reporting and methodological requirements of the protocol which shall entitle it to regain eligibility to participation in the flexibility mechanisms. Having said that, all compliance cases brought to the enforcement branch involved non-compliance with the methodological and reporting duties. All of such cases except the one involving Slovakia led to suspension of eligibility for the flexibility mechanisms. In practice the enforcement branch has issued a declaration of non compliance with methodological and reporting duties, suspended eligibility for flexibility mechanisms, ordered development of plans to rectify the non-compliance, and utilized the reinstatement rules under section X (2) of decision 27/CMP.1. These practices reveal certain variations from provisions for consequences under the enforcement branch (table 1). 7. Taking Stock: The Kyoto-Marrakesh Compliance System 7.1. Are the Enforcement Branch decisions enforceable? Even though negotiators have created an advanced compliance system, potential loopholes which reduce the power of the procedures to compel compliance have been observed by law pundits.153 For starters; a state which foresees that it would be declared non-compliant at the close of the first commitment period loses the incentive for making further (preferably stronger) commitments for the second commitment period. This may seem an old worry granted that the targets for the second commitment period have already been set.154 However the impact of the loophole remains large should the protocol survive for a third commitment period. Eventually this hampers the long term effort of mitigating the impacts of climate change. Adding to this is the absence of enforcement mechanism for the consequences to non-compliance with the substantive obligations of limitation (reduction) of emission. Stemming from the drawback of general international law, whether a non 152 KP-CP, section X (2), supra note 58. Hovi, J., Stokke, O.S. and Ulfstein, G., "Introduction and Main Findings" in Ulfstein et al., supra note 85, pp.1-14, at 11. 154 The Doha amendment, supra note 10. 153 42 complying party will accept and execute the decision of the enforcement branch more or less depends on the sincere cooperation of the party. These limitations are exasperated by the loosely constructed withdrawal rules of the protocol. By virtue of article 27 of the protocol, a party heading to non-compliance can resort to withdrawal from the protocol with a simple one year prior notice thereby easily evading the weight of non-compliance decision. Another dimension of critics is draws upon the attachment of the compliance procedures with the eligibility to the flexibility mechanisms particularly the international emissions trading under article 17 of the protocol. The very nature of these mechanisms being dependent on market transactions can lead to far reaching disturbances if a large economy (or an economy highly dependent on fossil fuel consumption) is declared non-compliant and as a result suspended from the international emissions trading. If such happens global economic repercussions are certain to ensue for the fact that the price of fossil fuel will change considerably due to absence of major stakeholder in the market.155It goes without saying that the might of such decisions will be stronger on parties who use to engage in emissions trading with the suspended party. These instances indicate that the punitive measures adopted against a non-complying party can in fact inflict more harm to other states than they do the culprit state.156 This is the context in which Jon Rovi and Steffen Kallbekken argued that Norway would suffer more due to non-compliance of another state than it would due to its own noncompliance.157 The complexity of such ramifications is likely to persuade the members of the enforcement branch to take consideration of these impacts. Thus far it cannot be ruled out that the enforcement branch may refrain from declaration of non-compliance of a state despite empirical prove of otherwise. Even when strictly applying the rules of non-compliance, it is far from obvious that the system always guarantees for punishment of a non compliant party.158 7.2. Reflection on the Legal Value of Consequences While the consequences of the facilitative branch, emanating from their very nature, are soft consequences aimed to buttress climate compliance, the enforcement branch is duty bound to apply both soft consequences and hard sticks depending on the nature of the case before it. Thus discussion 155 See generally: Hagem, C. and Westskog H., "Effective Enforcement and Double-edged Deterrents: How the Impacts of Sanctions also Affect Complying Parties" in Ulfstein et al., supra note 85, pp.107-120. 156 Ibid. 157 Rovi, J. and Kallbekken, S., " The price of non-compliance with the Kyoto Protocol: The remarkable case of Norway" (2007) 7 International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, pp 1-15. 158 Hovi, J., Stokke, O.S. and Ulfstein, G., "Introduction and Main Findings" in Ulfstein et al., supra note 85, pp.1-14, at 11. 43 on the legal character of the consequences of the facilitative branch suffers from shallow arguments due to the obviousness of the fact that failure to respond to the facilitation services of this branch most likely leads to triggering question of implementation before the enforcement branch. For the enforcement branch, the first consequence - a declaration of non-compliance does not, in itself, create a new obligation; it is rather directed at impacting the credibility and reputation of the subject state. The consequences related to development of plan and filing reports of progress are generally considered to be soft sanctions although they establish new obligations, they.159 The legal implication of consequences is rather crucial with the more hard consequences whose ramifications extend to economic and political situations of the countries. Hence the reference of consequences in this section corresponds to the hard sticks; namely suspension of eligibility of the flexibility mechanisms and deduction of assigned amounts for the second commitment period. Closely tied to the mode of adoption of the entire compliance procedure, the enforceability of the consequences of non-compliance was at the epicenter of a heated debate during the negotiations. Hence much of the argument advanced earlier regarding amendment as an option for adoption of the compliance procedures is also valid for the legal character of the consequences. Providing for necessity of an amendment to give legal effect to compliance consequences involves protracted acceptance and ratification procedure which tends to underplay the time essence of the consequences; not to mention its likelihood of opening doors for uneven treatment of parties. In spite of this major setback, the current arrangement has opted to pursue the amendment route. Accordingly the virtue of article 18 of the protocol mandatorily requires amendment of the protocol to give legal effect to a given compliance decision entailing binding consequence. In a way, turning down an amendment proposal for enforcing a given compliance consequence serves as a procedural guarantee of acquiring an opportunity to consent to be bound by the enforcement consequences.160 Prescribing for an amendment procedure does not however mean that decisions cannot be binding until and unless an amendment to that effect is secured and enforced. In fact the consequences by the enforcement branch are effective irrespective of absence of an amendment for binding status of the consequences and regardless of the interpretation of article 18 of the protocol.161 The international transaction log (ITL) ensures that a decision to the effect of suspension of eligibility and deduction of assigned amounts of a party are self-enforced. Functioning under the aegis of the secretariat, the ITL 159 Ulfstein G. and Werksman J., "The Kyoto Compliance System: Towards Hard Enforcement" in Ulfstein et al., supra note 85, pp.39-66 at 56. 160 Ibid. 161 Oberthur and Lefeber, supra note 124, at 83. 44 verifies transactions proposed by registries to check their consistency with the requirements of the protocol.162 As the ITL rejects to process transaction attempts made by a suspended party, the ERTs will ignore these transactions thereby effectively enforcing the decision of suspension from the carbon mechanisms.163 Furthermore if we are to see a declaration of non-compliance to emission commitments under article 3 (1) of the protocol, a deduction from the second commitment period will be automatically implemented through the ITL despite a claim by the concerned party that it is not bound by such deduction.164 As with the broader international law, it is hardly possible to order a state to do something in enforcing a given international decision, however the compliance procedures of the Kyoto Protocol have included an inbuilt mechanism to exclude the state from the benefits of the climate regime thereby giving effect to enforcement branch decisions. 9. Concluding Perspectives In the past couple of decades the international community has been giving a deserved attention to promotion of compliance with international law. Owing to the environment being a common concern, the notion of compliance as opposed to enforcement is reckoned with higher priority and importance in the development and operations of MEAs. The central question in this regard remains to be developing a mechanism which can ensure maximum compliance to MEAs. While various theories have been devoted to explain a strategy to this end, international relations experts have especially cultivated two approaches – the cooperative approach and the enforcement approach. It is hardly possible for any of them to claim universal acceptance. What is more; recent history of MEA compliance reveals a growing trend of fostering both theories in compliance applications.165 The specific strategy adopted by a certain MEA compliance procedure heavily relies on the substance of the MEA, the parties involved, the past experience, and the political context within which the compliance system is negotiated.166 As can be inferred from the procedures discussed in this study, the compliance system of the Kyoto Protocol indeed represents one of the most detailed compliance mechanisms operating in environmental regimes. Admittedly this owes its origin to the intense negotiation process involved in the design of the compliance system. The ostensible premise that non-compliance with climate 162 http://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol/registry_systems/itl/items/4065.php Oberthur and Lefeber, supra note 124, at 83.. 164 Ibid. 165 Doelle, M., Brunnee J. and Rajamani L. "Conclusion: promoting compliance in an evolving climate regime." in Brunnee, et al., supra note 93, pp 437-458 at 437. 166 Ibid. 163 45 commitments will be met with socio-economic repercussions has forced states to maintain articulated positions in the negotiations. With its facilitative and enforcement streams, the climate compliance system is adopted bespoke to the peculiarities of the regime in terms of distinguishing between soft procedural commitments and hard emission target commitments.167 As negotiators anticipated that the facets of achieving emission commitments would likely require major infrastructural arrangements by Annex I countries, they have entrusted the facilitative branch with a mandate of advising and technically supporting them. Accordingly facilitation tasks have topped the agenda during the first commitment period. The ERTs have constituted substantial facilitation with their expertise recommendations to parties on how to improve their reporting and methodological functions. From these experiences one can infer that it is the hope of the negotiators that achieving emission targets by the close of the first commitment period will be a natural consequence of continuous facilitation measures taken so far. Although the first commitment period is closed at the time of writing, the accounting for the last year is not complete and thus a final reckoning of compliance of parties with emission targets under article 3(1) remains outstanding. Appreciation of the extensiveness of the climate compliance system should not, however, overlook the shortcomings identified in the practical experiences gained so far. Most prominently the current compliance system fails provide for effective method to enforce the decisions of the enforcement branch. In fact the compliance procedure is supplemented by the ITL which ensures automatic implementation of enforcement branch decisions. However the loosely crafted withdrawal rules of the protocol under its article 27 tend to make the compliance procedures and the enforcement mechanisms futile. When push comes to shove regarding its emissions commitments, any state can easily evade compliance decisions by withdrawing from the protocol. This is not just a hypothetical woe; but rather a practical specter as seen in the case of Canada withdrawing from the protocol followed by Japan, New Zealand and Russian Federation refraining from binding obligation in the second commitment of the protocol.168 Another apparent loophole of the compliance rules relates to the triggering mechanism. Looking at all the questions implementation so far dealt with, one can see that all of them have been triggered as a result of ERT report. This shows that the self triggering and party to party triggering have not been used so far save to the exception of the question launched by South Africa. While non existence of party to party triggering can be justified in light of maintaining inter-state diplomacy, the lack of self 167 168 Ibid. The Doha Amendment, supra note 10. 46 trigger is an indication of parties not approaching the facilitative branch looking for assistance. Admittedly lack of capacity of facilitative branch to launch a question of implementation has marginalized its role as it has to wait for other bodies to trigger. Considering the silence of the other triggering mechanisms, a positive step forward could be empowering the facilitative branch to conduct periodic consultation with parties thus making it more proactive in promoting compliance.169 A general evaluation of the design and experience of the climate compliance system certainly gives a positive impression especially in convincingly arguing that enforcement can be a function of compliance system in MEAs. Despite the rooms for improvement the current system has a strong procedural and institutional setup which can be a model for other MEAs. The efficiency of ERTs in providing facilitation on similar or better level with the facilitative branch and identifying questions of implementation perhaps remains the most imperative practical aspect of the Kyoto-Marrakesh compliance system. In the just started second commitment period, chances are that the compliance procedures will continue to operate more or less efficiently in regards questions of implementation on reporting and methodological commitments.170 As the mandate of the facilitative branch regarding these questions of implementation draws to an end, the procedures of determination of non-compliance with emission reduction commitments are set to be tested. An interesting turn of events may also unfold in the face of developing a new climate regime where the arrangement of entrusting a body to deal with compliance issues may be rechecked in reference to the merits and demerits it sustained. 169 170 Doelle, et al., M., supra note 165, at 440. Ibid at 447. 47 Index of documents 1992 Report of the Fourth Meeting of the Parties to the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer: Annex V, UNEP/OzL.Pro.4/15 1992 United Nations Frame Work Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) http://unfccc.int/key_documents/the_convention/items/2853.php. 1997 Protocol to the UNFCCC (otherwise known as Kyoto Protocol) http://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol/status_of_ratification/items/2613.php 1997 1998 The Bryd-Hagel Resolution UNEP/OzL.Pro.10/9 Report of the Tenth Meeting of the Parties to the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer: Annex II 1998 UNEP/OzL.Pro.10/9, Report of the Tenth Meeting of the Parties to the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer 1999 FCCC/SB/1999/MISC.12, Procedures and Mechanisms relating to Compliance under the Kyoto Protocol: Submissions by Parties 1999 Decision 1/CP.4., "The Buenos Aires Plan of Action" in FCCC/CP/1998/16/Add.1 1999 Decision 8/CP.4, Preparations for the first session of the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol: matters related to decision 1/CP.3, paragraph 6, Annex I and II in FCCC/CP/1998/16/Add.1 1999 FCCC/SB/1999/MISC.4, Procedures and Mechanisms relating to Compliance under the Kyoto Protocol: Submissions by Parties 2000 FCCC/SB/2000/MISC.2, Procedures and Mechanisms relating to Compliance under the Kyoto Protocol: Submissions by Parties. 2001 UNEP/GCSS.VII/4/Add.2, Draft Guidelines for Compliance with and Enforcement of multilateral environmental agreements 48 2001 Decision 5/CP.6, The Bonn Agreements on the implementation of the Buenos Aires Plan of Action, Annex, section VIII in FCCC/CP/2001/5 2001 International Law commission (ILC) Draft articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts, 2001 2002 Draft Guidelines for Compliance with and Enforcement of multilateral environmental agreements, UNEP 2002 Decision 24/CP.7, Procedures and Mechanisms relating to Compliance under the Kyoto Protocol in FCCC/CP/2001/13/Add.3 2003 Decision VI/12, Establishment of Mechanism for Promoting Implementation and Compliance, UNEP/CHW.6/40, Basel Convention Compliance Procedures 2003 ECE/CEP/107, Guidelines for Strengthening Compliance with and Implementation of multilateral environmental agreements in the ECE Region 2004 Decision BS-I/7, Establishment of Procedures and Mechanisms on Compliance under the Cartagena Protocol on Biodiversity, UNEP/CBD/BS/COP-MOP/1/15 2004 Decision I/7; "Review of Compliance", (ECE/MP.PP/2/Add.8); Aarhus Convention Compliance Procedures 2006 CC-2006-14-2/Slovenia/FB, Preliminary Examination: Party concerned, Slovenia 2006 CC-2006-8-3/Latvia/FB, Preliminary Examination: Party concerned, Latvia 2006 UNEP Manual on Compliance with and Enforcement of Multilateral Environmental Agreements 2006 Decision 15/CMP.1, Guidelines for the preparation of the information required under Article 7 of the Kyoto Protocol, FCCC/KP/CMP/2005/8/Add.2 2006 Decision 13/CMP.1, Modalities for the accounting of assigned amounts under Article 7, paragraph 4, of the Kyoto Protocol FCCC/KP/CMP/2005/8/Add.2 49 2006 Decision 2/CMP.1, Principles Nature and Scope of Mechanisms Pursuant to Article 6, 12 and 17 of the Kyoto Protocol, FCCC/KP/CMP/2005/8/Add.1 2006 Decision 22/CMP.1, Guidelines for Review under article 8 of the Kyoto Protocol in FCCC/KP/CMP/2005/8/Add..3 2006 Decision 27/CMP.1, Procedures and Mechanisms Relating to Compliance under the Kyoto Protocol, Annex, in FCCC/KP/CMP/2005/8/Add.3, KP-CP 2006 CC-2006-1-1/FB, A letter to the Chairman of the Facilitative Branch of the Compliance: Compliance with Article 3.1 of the Kyoto Protocol 2006 CC-2006-1-2/FB, Report to the Compliance Committee on the Deliberations in the Facilitative Branch Relating to the Submission Entitled “Compliance with Article 3.1 of the Kyoto Protocol” (CC-2006-1/FB to CC-2006-15/FB) 2007 Decision 4/CMP.2, Compliance Committee, FCCC/KP/CMP/2006/10/Add.1 2007 IPCC, Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the IPCC. 2008 CC-2007-1/Greece/EB, Question of Implementation-Greece 2008 CC-2007-1-8/Greece/EB, Final Decision: Party concerned; Greece 2008 CC-2007-1-1/Greece/EB, Report of the review of the initial report of Greece: note by the secretariat 2008 CC-2007-1-2/Greece/EB, "Decision on Preliminary Examination: Party concerned; Greece 2008 CC-2008-1-6/Canada/EB, Decision not to Proceed Further: Party concerned; Canada 2008 CC-2007-1-13/Greece/EB, Decision under Paragraph 2 of Section X: Party concerned; Greece 2008 CC-2008-1/Canada/EB, Question of Implementation-Canada 2009 CC-2009-1-8/Croatia/EB, Final Decision: Party concerned; Croatia 50 2009 Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center: Top 20 countries by total fossil fuel CO2 emissions, 2009 2009 CC-2009-1/Croatia/EB, Question of Implementation-Croatia 2010 FCCC/KP/CMP/2010/2, Appeal by Croatia against a final decision of the enforcement branch of the Compliance Committee 2012 CC-2012-1-9/Slovakia/EB, " Final Decision: Party concerned; Slovakia 2012 CC-2009-1-14/Croatia/EB, Decision under Paragraph 2 of Section X: Party concerned; Croatia 2012 CC-2012-1-6/Slovakia/EB, "Decision on a Disagreement whether to apply Adjustments to Inventories under Article 5, Paragraph 2, of the Kyoto Protocol: Party concerned: Slovakia 2012 FCCC/ARR/2011/SVK, Report of the individual review of the annual submission of Slovakia submitted in 2011 2013 Decision 1/CMP.8, Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol Pursuant to its Article 3, paragraph 9 (the Doha Amendment) in FCCC/KP/CMP/2012/13/Add.1 2013 CC-2012-1/Slovakia/EB, Question of Implementation-Slovakia 51 Bibliography Birnie, P., Boyle, A., and Redgwell, C. International law & the Environment, Third edition (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2009) Brunnee J. "Enforcement Mechanisms in International Law and International Environmental Law" in Beyerlin U., Stoll P.T., and Wolfrum R. (eds) Ensuring Compliance with Multilateral Environmental Agreements: A Dialogue between Practitioners and Academia (Brill Academic Publishers, 2006) Brunnee, J., "COPing with Consent: Law Making Under Multilateral Environmental Agreements." (2002) 15 Leiden Journal of International Law Brunnee, J., "The Kyoto Protocol: A Testing Ground for Compliance Theories?" Heidelberg Journal of International Law (2003) Garner, B., Black's Law Dictionary, 9th edition (2009) at 608 Hagem, C., and Westskog, H., "Effective Enforcement and Double-edged Deterrents: How the Impacts of Sanctions also Affect Complying Parties" in Beyerlin U., Stoll P.T., and Wolfrum R. (eds) Ensuring Compliance with Multilateral Environmental Agreements: A Dialogue between Practitioners and Academia (Brill Academic Publishers, 2006) Chayes, A., and Chayes, A.H., The New Sovereignty (Harvard University Press, 1995) Doelle M., "Experience with the facilitative and enforcement branches of the Kyoto compliance system" in Brunnee, J., Doelle., M., and Rajamani, L. (eds), Promoting Compliance in an Evolving Climate Change, (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2012) Doelle, M., Brunnee., J., and Rajamani L. "Conclusion: promoting compliance in an evolving climate regime." in Brunnee, J., Doelle, M., and Rajamani, L. (eds), Promoting Compliance in an Evolving Climate Change, (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2012) Downs, G.W., Rocke, D.M., and Barsoom, P.N. "Is the Good News about Compliance Good News about Cooperation?" (1996) 50 International Organization 52 Epiney A., "The Role of NGOs in the Process of Ensuring Compliance with MEAs" in Beyerlin U., Stoll P.T., and Wolfrum R. (eds) Ensuring Compliance with Multilateral Environmental Agreements: A Dialogue between Practitioners and Academia (Brill Academic Publishers, 2006) Gulbrandsen, L.H., and Andresen, S., "NGO Influence in the Implementation of the Kyoto Protocol: Compliance Flexibility Mechanisms, and Sinks"(2004) 4 Global Environmental Politics, pp 5475. Guzman, A.T., How International Law Works: A Rational Choice Theory (Oxford University Press, New York, 2008) Henkin, L., How Nations Behave (Columbia University Press, 1979) Hovi, J., and Halvorseen, A., "The nature, origin and impact of legally binding consequences: the case of the climate regime" (2006) 6 International Environmental Agreements, Hovi J., Stokke, O.S., and Ulfstein G., "Introduction and Main Findings" in Stokke, O.S., Hovi J., and Ulfstein, G. (eds) Implementing the Climate Regime: International Compliance (Earthscan and International Institute for Environment and Development, UK 2005) Jacur, F.R.," Triggering Non-Compliance Procedures" in Treves, T., Pineschi, L., Tanzi, A., Pitea, C., Ragni, C. and Jacur, F.R. (eds), Non-Compliance Procedures and Mechanisms and Effectiveness of International Environmental Agreements (After this called Non-Compliance Procedures and Mechanisms, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2009) Depledge, J. "Continuing Kyoto: Extending Absolute Emission Caps to Developing Countries," in Baumert, K.A., Blanchard, O., Llosa, S., and Perkaus, J.F. Building on the Kyoto Protocol: Options to Protect the Climate (World Resources Institute, 2002l), pp 31-60 Mehling, M., "Enforcing Compliance in an Evolving Climate Change" in in Brunnee, J., Doelle., M. and Rajamani, L. (eds), Promoting Compliance in an Evolving Climate Change, (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2012) 53 Mitchell, R.B., International Oil Pollution at Sea: Environmental Policy and Treaty Compliance: Environmental Policy and Treaty Compliance (Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 1994) Mrema, E.M., "Cross-Cutting Issues to Ensuring Compliance with MEAs" in, Ensuring Compliance with Multilateral Environmental Agreements: A Dialogue between Practitioners and Academia (Brill Academic Publishers, 2006), pp.201-229 Oberthur, S., and Lefeber R., " The Experience of the First Five Years of the Kyoto Protocol’s Compliance System" in Couzens E., and Honkonen T. (eds) International Environmental Law Making and Diplomacy Overview 2012 (University of Eastern Finland, Finland, 2011) Raustiala, K., and Slaughter, A. "International Law, International Relations and Compliance" in Carlnaes, W., Risse, T., and Simmons, B. (eds), The Handbook of International Relations (Sage Publications Ltd, 2002) Rovi., J., and Kallbekken S., " The price of non-compliance with the Kyoto Protocol: The remarkable case of Norway" (2007) 7 International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, pp 1-15 Sand, P.H., "Sanctions in case of Non-Compliance and State Responsibility: Pacta sunt servanda - Or Else?" in Beyerlin U., Stoll P.T., and Wolfrum R. (eds) Ensuring Compliance with Multilateral Environmental Agreements: A Dialogue between Practitioners and Academia (Brill Academic Publishers, 2006), pp.259-271. Simmons, B.A., "Compliance with International Agreements" (1998) 1 Annual Review of Political Science, Reus-Smit, C.(eds), The Politics of International Law (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004) Ulfstein G. and Werksman J., "The Kyoto Compliance System: Towards Hard Enforcement" in Stokke, O.S., Hovi J., and Ulfstein G. (eds) Implementing the Climate Regime: International Compliance (Earthscan and International Institute for Environment and Development, UK 2005) 54 Ulfstein, G., and Werksman, J., "The Kyoto Compliance System: Towards Hard Enforcement" in Stokke, O.S., Hovi J., and Ulfstein G. (eds) Implementing the Climate Regime: International Compliance (Earthscan and International Institute for Environment and Development, UK 2005) Victor, D.G., "The Operation and Effectiveness of the Montreal Protocol’s Non-Compliance" in Victor, D.G., Raustiala, K., and Skolnikoff, B.E., (eds), Implementation and Effectiveness of International Environmental Commitments: Theory and Practice (International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, 1998), pp 137-177 Young, O.R., International Governance: Protecting the Environment in Stateless Society, (Cornell University, 1994) Treves, T., "Non-Compliance Mechanisms in Environmental Agreements: The Research Method Adopted" in Treves, T., Pineschi, L., Tanzi, A., Pitea, C., Ragni, C. and Jacur, F.R. (eds), NonCompliance Procedures and Mechanisms and Effectiveness of International Environmental Agreements (T.M.C. Asser Press, The Hague, 2009), pp 1-10 Pineschi, L., "Non-Compliance Procedures and the Law of State Responsibility" in Treves, T., Pineschi, L., Tanzi, A., Pitea, C., Ragni, C. and Jacur, F.R. (eds), Non-Compliance Procedures and Mechanisms and Effectiveness of International Environmental Agreements (T.M.C. Asser Press, The Hague, 2009), pp 483-497. Treves, T., "The Settlement of Disputes and Non-Compliance Procedures", in Treves, T., Pineschi, L., Tanzi, A., Pitea, C., Ragni, C. and Jacur, F.R. (eds), Non-Compliance Procedures and Mechanisms and Effectiveness of International Environmental Agreements (T.M.C. Asser Press, The Hague, 2009), pp 499-518 55