aromatase activity in receptor negative breast and endometrial

реклама

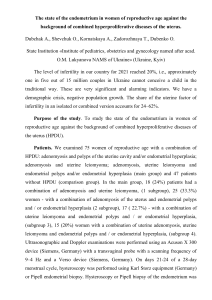

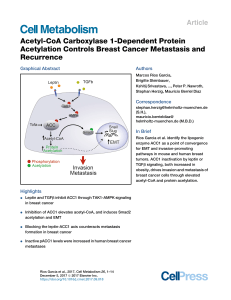

228 Exp Oncol 2003 25, 3, 228-230 Experimental Oncology 25, 228-230, 2003 (September) AROMATASE ACTIVITY IN RECEPTOR NEGATIVE BREAST AND ENDOMETRIAL CANCER L.M. Berstein1, *, A. Kovalevskij1, A. Larionov1 , E. Tsyrlina1, D. Vasilyev1, T. Zimarina1, J.H.H. Thijssen2 1 Laboratory of Oncoendocrinology, N.N. Petrov Research Institute of Oncology, St.Petersburg 197758, Russia 2 ASL Endocrinology, University Medical Center, Utrecht 3508 AB, The Netherlands ÀÊÒÈÂÍÎÑÒÜ ÀÐÎÌÀÒÀÇÛ Â ÊËÅÒÊÀÕ ÐÅÖÅÏÒÎÐÍÅÃÀÒÈÂÍÛÕ ÎÏÓÕÎËÅÉ ÌÎËÎ×ÍÎÉ ÆÅËÅÇÛ È ÝÍÄÎÌÅÒÐÈß Ë.M. Áåðøòåéí1, *, A. Êîâàëåâñêèé1, A. Ëàðèîíîâ1, E. Öûðëèíà1, Ä. Âàñèëüåâ1, T. Çèìàðèíà 1, Äæ. Ã.Ã. Òèññåí2 1 Ëàáîðàòîðèÿ îíêîýíäîêðèíîëîãèè, Íàó÷íî-èññëåäîâàòåëüñêèé èíñòèòóò îíêîëîãèè èì. ïðîô. Í.Í. Ïåòðîâà, Ñàíêò-Ïåòåðáóðã, Ðîññèÿ 2 Ëàáîðàòîðèÿ ýíäîêðèíîëîãèè, Ìåäèöèíñêèé öåíòð óíèâåðñèòåòà, Óòðåõò, Íèäåðëàíäû Among the factors for estrogen and progesterone receptors (ER and PR) negativity of tumors of reproductive tissue special attention is attracted by ability of the tumor produce estrogens (as intratumoral regulators of ER and PR) through reaction of aromatization. 101 samples of tumor tissue (64 cases of breast cancer and 37 cases of endometrial carcinomas) mostly from postmenopausal women were studied. When combined group of the tumors was divided on the basis of receptor-negativity or positivity (with cut-point correspondingly ≤ and > 10 fM/mg protein) among samples with higher aromatase activity (> 7 fM/mg protein/h), a tendency to higher number of ER-negative tumors was found (p = 0.07). Such association was significant for breast (p = 0.04) but not for endometrial cancer (p > 0.5) samples. No evidence of PR contents dependence of tumor aromatase activity was revealed which may be connected with disturbance of estrogen signal transfer. Thus, inverse relation between steroid receptor levels and aromatase activity may be tissue- and receptor type-dependent. Key words: aromatase, estrogen receptors, progesterone receptors, breast cancer, endometrial cancer. Ñðåäè ôàêòîðîâ, ñïîñîáñòâóþùèõ âîçíèêíîâåíèþ ðåöåïòîðíåãàòèâíûõ íîâîîáðàçîâàíèé ðåïðîäóêòèâíîé ñèñòåìû, îñîáîå âíèìàíèå ïðèâëåêàåò ñïîñîáíîñòü îïóõîëåâîé òêàíè ïðîäóöèðîâàòü ýñòðîãåíû (êàê âíóòðèîïóõîëåâûå ðåãóëÿòîðû ýêñïðåññèè ðåöåïòîðîâ ýñòðîãåíà è ïðîãåñòåðîíà) íà îñíîâå ðåàêöèè àðîìàòèçàöèè àíäðîãåííûõ ïðåäøåñòâåííèêîâ.  íàñòîÿùåé ðàáîòå èññëåäîâàëè 101 îáðàçåö îïóõîëåâîé òêàíè ïðåèìóùåñòâåííî îò áîëüíûõ ðàêîì ìîëî÷íîé æåëåçû (n = 64) è ýíäîìåòðèÿ (n = 37) â ïîñòìåíîïàóçàëüíûé ïåðèîä. Ïîñëå ðàçäåëåíèÿ âñåõ îïóõîëåé íà îñíîâàíèè îòñóòñòâèÿ èëè ïðèñóòñòâèÿ â íèõ ðåöåïòîðîâ (ñ ãðàíèöåé íà óðîâíå 10 ôÌ/ìã áåëêà) â íîâîîáðàçîâàíèÿõ ñ áîëåå âûñîêîé àêòèâíîñòüþ àðîìàòàçû (> 7 ôÌ/ìã áåëêà/÷) áûëî îáíàðóæåíî áîëüøåå ÷èñëî ÝÐ-íåãàòèâíûõ îïóõîëåé. Òàêàÿ çàêîíîìåðíîñòü äîñòèãàëà ñòàòèñòè÷åñêîé çíà÷èìîñòè â îïóõîëÿõ ìîëî÷íîé æåëåçû, íî íå áûëà ñâîéñòâåííà íîâîîáðàçîâàíèÿì ýíäîìåòðèÿ. Çàâèñèìîñòè óðîâíÿ ÏÐ îò àêòèâíîñòè àðîìàòàçû â îïóõîëåâîé òêàíè îáíàðóæåíî íå áûëî, ÷òî ìîæåò áûòü àññîöèèðîâàíî ñ íàðóøåíèÿìè â ïåðåäà÷å ýñòðîãåííîãî ñèãíàëà. Èíâåðñíûå âçàèìîîòíîøåíèÿ ìåæäó ýñòðîãåíïðîäóöèðóþùåé ñïîñîáíîñòüþ îïóõîëè è ñîäåðæàíèåì â íåé ñòåðîèäíûõ ðåöåïòîðîâ ìîãóò, òàêèì îáðàçîì, áûòü òêàíå- è ðåöåïòîðñïåöèôè÷íûìè. Êëþ÷åâûå ñëîâà: àðîìàòàçà, ðåöåïòîðû ýñòðîãåíîâ è ïðîãåñòåðîíà, ðàê ìîëî÷íîé æåëåçû, ðàê ýíäîìåòðèÿ. Steroid receptor status remains the most reliable predictor of response to hormonal therapy both in breast and endometrial cancer [1, 2]. Receptor-negative cancers of breast and endometrium make-up at least 30– 40% of all these tumors cases [3, 4] and demonstrate significantly worsier prognosis in comparison with receptor-positive observations [1, 2]. This explains an importance of the evaluation of possible factors which ma y influence contents, initial presence or loss of steroid receptors in tumor tissue. Received: July 9, 2003. *Correspondence: Fax 7-812-596-8947; E-mail: levmb@endocrin.spb.ru Abbreviations used: ER — estrogen receptors; PR — progesterone receptors. Generally, two hypotheses have been raised about the relationship between steroid receptor-positive and receptor-negative cancers. One hypothesis considers receptor, and namely estrogen (ER) or progesterone receptor (PR), status as an indicator of a different stage of the disease. The other regards R-positive and R-negative tumors as different entities [5]. Although the latter possibility suggests that receptor status of a tumor is determined early in its natural history [6] at the same time it underlines also the need for search of the factors of hormonal nature under which action receptor status of the neoplasm can be changed into positive or negative one. Estrogens should be considered among such factors first of all due to their ability influence inversely Experimental Oncology 25, 228-230, 2003 (September) et al [16] with minor modifications [17]. The receptor activity was expressed as fM/mg protein. Protein content was determined by the Lowry method. Statistical analysis was performed by methods allowing for means and standard errors. The significance of the differences between the groups was tested using xi-square approach by computerized program (SigmaPlot). The differences with p ≤ 0.05 were considered as significant. Individual values of aromatase activity in studied breast and endometrial cancer samples varied between 0 and 41.7 fM/mg protein/h. Analysis of the distribution of individual variants revealed that median of aromatase activity in collected material was equal 7.2 fM/mg protein/h. According to this, further analysis of the association with steroid receptor content was performed in groups with aromatase activity levels below and higher than 7 fM/mg protein/h (Table, Figure). As shown in Table, among combined group of breast and endometrial carcinomas with aromatase activity > 7 fM/mg protein/h incidence of appearance of estrogen receptor-negative tumors (with ER content < 10 fM/mg protein) demonstrated tendency to decrease in comparison with cancers characterized with lower level of estrogen-producing activity (p = 0.07). Incidence of progesterone receptor-negative and PR-positive tumors in this material did not differ and actually was practically the same (p > 0.9). These observations were confirmed also by χ2-coefficients values which were equal correspondingly 2.96 (for ER) and 0.004 (for PR). At the same time, when groups of breast and endometrial carcinomas were evaluated separately the following picture emerged. In breast cancer group ER-negative tumors appeared in 12 of 33 cases when aromatase activity was higher that 7 fM/mg protein/h and in 5 of 31 cases when this activity was < 7 fM/mg protein/h (χ 2 4.47, p = 0.04; see Figure). Progesterone re30 χ 2 4.47 χ 2 2.03 25 Number of cases expression of ER and PR in breast cancer cell culture [7]. Suppressive effect of estrogen on ER expression and content depends though of estrogen concentration and several other conditions and it is of interest that long-term estrogen replacement therapy in menopause not decreases but increases number of ER-positive tumors [8]. On the other side, although PR is as a rule induced by estrogens and is regarded as a marker of estrogen-responsiveness, decrease in tumor PR content may be related not only to estrogen deficiency but also to defects in estrogen signal transduction [7]. Intratumoral estrogenic influences on ER and PR expression and content can be important as well. In regard to this it should be mentioned that estrogen-producing ability of tumor, or in other words its aromatase activity, was studied so far rather rarely as a determinant of receptor positivity or negativity. Besides, although conclusions which have been made were not monotonous [9–11], in two papers [12, 13] negative association between ER content and aromatase activity in breast cancer tissue was revealed. On the other side, in only data we are aware of related to endometrial cancer [14] no connection between steroid receptor content and activity of aromatase in tumor tissue was discovered. Taking into account above mentioned information we evaluated changes in aromatase activity characteristic for receptor-negative breast and endometrial cancer. Totally tumor samples from 101 patients (64 with breast cancer and 37 with endometrial cancer) have been evaluated. 87 patients (or 86.3%) had been postmenopausal for at least 1 year. The majority of the patients were at clinical stage I-II. 92% of breast tumors have had size T1–2, 60% did not demonstrate damage of regional lymphatic nodes. Among endometrial cancers, morphologically only endometrioid adenocarcinomas mostly in grades G1–2 of differentiation were present in this material. Collected tissue samples were immediately transferred into laboratory and were placed into liquid nitrogen for further processing. Aromatase activity in tumor tissue was estimated by measuring 3H2O release from 3H-1-β-androstenedione (NEN, Boston, USA; specific activity, 25.4 Ci/mM) as described [15]. Briefly, the reaction mixture (which contained tumor homogenate, NADPH regeneration system and labeled androgenic precursor) was incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. Then reaction was stopped by adding 5 vol of cold chloroform, and 5% suspension of activated charcoal (Norit A) was added to the water phase. The fraction containing 3H2O was separated by centrifugation, and counting was performed with dioxane scintillator. Results were presented in fM/mg protein/h. Estrogen and progesterone receptor contents in tumor tissue were evaluated by the dextrane-charcoal radioligand assay according to Saez 229 20 15 10 5 0 ER(–) ER(+) Arom < PR(–) PR(+) Arom > Figure. Distribution of receptor-negative and receptor-positive cases in regard to aromatase activity in the group of studied breast cancers. χ2 -coefficient demonstrates significant difference when it is ≥ 3.84. ER (–) and PR (–): ≤ 10 fM/mg protein; ER (+) and PR (+): > 10 fM/mg protein; Arom <: less than 7 fM/mg protein/h; Arom >: equal or higher than 7 fM/mg protein/h Table. Incidence of recept or-negative and receptor-posit ive cases among breast and endometrial cancers wit h different aromat ase activ ity Parameter Aromatase activity is lower ( ≤ 7 fm/mg protein/h) Aromat ase activit y is higher (> 7 fm/mg protein/ h) ER PR ER PR > 10 fM > 10 f M > 10 fM > 10 fM ≤ 10 fM ≤ 10 f M ≤ 10 fM ≤ 10 fM Number of cases 11 37 26 30 16 27 20 25 Incidence of R(–) tumors,% 22.9 ± 6.1* 46.4 ± 6.6 37.2 ± 7.3* 44.4 ± 6.6 *p = 0.07. 230 ceptor-negative breast cancers were revealed correspondingly in 13 of 33 cases (aromatase activity > 7 fM/mg protein/h) and in 8 of 33 cases (aromatase activity < 7 fM/mg protein/h), χ 2 2.03, p = 0.09. In endometrial cancer group distribution of ER-negative and ER-positive cases as well as PR-negative and PR-positive cases in tumors with aromatase activity higher or lower than median value was practically equal, and this was confirmed by corresponding χ2 values (for ER χ 2 0.43, p > 0.4; for PR χ2 1.45, p > 0.1). In summary, it may be concluded that association between estrogen-producing activity of studied tumors and their steroid receptor content is characterized according to received data by receptor- and tumor-speci ficity: namely, reciprocal relationships between these parameters are revealed only in relation of estrogen (and not progesterone) receptors and in regard of breast (and not endometrial) cancer. Thus, higher rates of intratumoral estrogens produced through aromatase mechanism can lead to inhibition of estrogen receptor expression first of all in breast cancer tissue apparently due to higher importance of ER’s in breast than in endometrial cancers [2, 4, 6]. Absence of significant relationship bet ween aromatase activity and progesterone content independently of tissue context demonstrates, as it seems, that estrogen dependence of PR in cancer tissue is lost more fast (that it appears in regard of ER) although does not explain, at the same time, why ER(+),PR(–) cancers are more frequent than ER(–), PR(+) ones [18]. The latter observation may be explained by other reasons, including mechanisms related to so called phenomenon of switching of estrogen effect [19]. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS These studies were partly supported by grants from RFBR (04-49282), INTAS (01-434) and MS (program 29). REFERENCES 1. Habel LA, Stanford JL. Hormone receptors and breast cancer. Epidemiol Rev 1993; 15: 209–19. 2. Emons G, Fleckenstein G, Hinney B, Huschmand A, Heyl W. Hormonal interactions in endometrial cancer. Endocrine-Related Cancer 2000; 7: 227–42. 3. Yasui Y, Potter JD. The shape of age-incidence curves of female breast cancer by hormone-receptor status. Cancer Causes Control 1999; 10: 431–7. 4. Saegusa M, Okayasu I. Changes in expression of estrogen receptors alpha and beta in relation to progesterone receptor and pS2 status in normal and malignant endometrium. Jpn J Cancer Res 2000; 91: 510–8. 5. Zhu K, Bernard LJ, Levine RS, Williams SM. Estrogen receptor status of breast cancer: a marker of diffe- Experimental Oncology 25, 228-230, 2003 (September) rent stages of tumor or different entities of the disease? Med Hypotheses 1997; 49: 69–75. 6. Scawn R, Shousha S. Morphologic spectrum of estrogen receptor-negative breast carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2002; 126: 325–30. 7. Fazzari A, Catalano MG, Comba A, Becchis M, Raineri M, Frairia R, Fortunati N. The control of estrogen and progesterone receptor expression in MCF-7 breast cancer cells: effects of estradiol and sex hormone binding globulin. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2001; 172 : 31–6. 8. Colditz GA. Relationship between estrogen levels, receptors, use of hormone replacement therapy, and breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998; 90: 814–23. 9. Silva MC, Rowlands MG, Dowsett M, Gusterson B, McKinna JA, Fryatt I, Coombes RC. Intratumoral aromatase as a prognostic factor in human breast carcinoma. Cancer Res 1989; 49: 2588–91. 10. Miller WR, Mullen P. Factors influencing aromatase activity in the breast. J Steroid Mol Biochem Mol Biol 1993; 44: 597–604. 11. Bolufer P, Ricart E, Iluch A. Aromatase activity and estradiol in human breast cancer: its relationship to estradiol and EGF receptors and to tumor-node metastasis staging. J Clin Oncol 1992; 10: 438–46. 12. Abul-Hajj YH, Iverson R, Kiang DT. Aromatization of androgens by human breast cancer. Steroids 1979; 33: 205–22. 13. Esteban JM, Warsi Z, Haniu M, Hall P, Shively JE, Chen S. Detection of intratumoral aromatase in breast carcinomas. An immunohistochemical study with clinicopathologic correlation. Am J Pathol 1992; 140: 337–43. 14. Watanabe K, Sasano H, Harada N, Ozaki M, Niikura H, Sato S, Yajima A. Aromatase in human endometrial carcinoma and hyperplasia. Immunohistochemical, in situ hybridization, and biochemical studies. Am J Pathol 1995; 146: 491–500. 15. Tilson-Mallett N, Santner SJ, Feil PD, Santen RJ. Biological significance of aromatase activity in human breast tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol 1983; 57 : 1125–8. 16. Saez S, Martin PM, Chouvet CD. Oestradiol and progesterone receptor levels in human breast adenocarcinoma in relation to plasma estrogen and progesterone levels. Cancer Res 1978; 38: 3468–73. 17. Tsyrlina EV, Semiglazov VF, Moiseenko VM, Boronoeva TP. Study of the role of steroid receptors in human breast cancer. Neoplasma 1985; 32: 463–7. 18. Potter JD, Cerhan JR, Sellers TA, McGovern PG, Drinkard C, Kushi LR, Folsom AR. Progesterone and estrogen receptors and mammary neoplasia in the Iowa Women’s Health Study: how many kinds of breast cancer are there? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1995; 4: 319–26. 19. Berstein LM, Tsyrlina EV, Bychkova N, Kalinina N, Gamajunova V, Vasilyev D, Kovalenko I. Switching (overtargeting) of estrogen effects and its potential role in hormonal carcinogenesis. Neoplasma 2002; 49: 21–5.