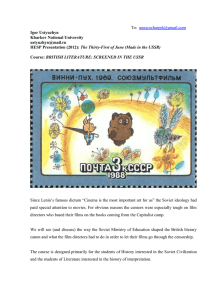

INTRODUCTION While “major events from the past have often been the staple of world cinema”1, world cinema has not been at all genuine or accurate in its retelling of such events. None the less, this dissertation aims to explore the notion of cinema as a historical record of humanity, though not at all in relation to its retelling of factual events... One of the most interesting aspects of film is the way that it has transformed and evolved throughout history in different national and cultural arenas. Since its conception in the late 19th century cinema has had many faces, from French new wave to British new wave to Italian neo realism to German expressionism and so on and so on, each movement having been a result or reflection (at least in part) of some social, cultural, political, and or economic development. It is with this in mind that I write that cinema is a product of society and as such has developed along side society, often reflecting our own history such as our wars, technological developments, and political and cultural revolutions. For instance cinema from America in the 1920s documents the eroticism of the U.S. at the time (which would soon be vanquished by the Production code in 1930), and the coming of sound in films such as The Jazz Singer (1927), while cinema from Russia in the 1920s documents the nations economic and artistic strength, and the beginnings of montage in film.2 Perhaps the very environment surrounding a film’s production is influential and evident in the film itself. I aim to explore this potential relationship between cinema and society through a comparative study to see whether social, economic, political, and other 1 Gillespie, D. Russian Cinema, p59 “Timeline of Influential Milestones and Turning Points in Film History” http://www.filmsite.org/milestones1920s.html, (20 th March 2008) 2 1 circumstances surrounding the production of a film can be used to explain and understand certain key aspects of the film itself. Hence this dissertation will compare Disney’s 1951 animation, Alice in Wonderland with Ephrem Pruzhanskii’s 1981 animated short, Alisa in the Land of Miracles to explore what differences exist between the two films and whether these differences can be understood or explained by the contexts in which these films were made. I have chosen to look at Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and these two adaptations in particular, for a number of reasons. Firstly, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is a book that I am personally very interested in, and that furthermore has been appropriated and re-appropriated into popular culture many times, in many different ways, through many different films, thus it lends itself nicely to this project in that it is a flexible text and there are at least fourteen cinematic adaptations of the text to choose from.3 It is also a very controversial text in that, while it is quintessentially a children’s book, it seemingly has elements of psychedelia, psychosis and other adult themes in it, as many have argued over the years. Hence it is open to manipulation and alternative understandings, which provides some leeway for filmmakers to express themselves and / or for culture and society to manifest themselves through the process of production, and it is precisely this ‘manifestation’ which I aim in explore. As for these two films in particular, first and foremost they are quite comparable in that they are both animations, and are both primarily intended for children, unlike, for “Alice in Wonderland; Film and TV productions across the years” http://www.alice-inwonderland.fsnet.co.uk/film_tv_intro.htm, (20 th February 2008) 3 2 instance, Jan Švankmajer’s dark and troubling Alice (1988) which features crawling pieces of meat and walking, talking, stalking skeletal creatures. Being children’s films, they do not openly or directly communicate any social, cultural or political critique, thus there is some inquiry necessary to explore the possibility of social, political and economic influence in these films. Being animations, Alice and Alisa function quite differently to live-action film as they are wholly different creatures. The fact that everything in animation is (or was until recently) hand drawn means that visual aspects are completely imagined and hence any clear connection made to a reality (a real time and place) is more purposeful and meaningful than if it was simply filmed there. Otherwise put, “images in animation are never accidental.”4 Secondly, and very importantly, the stark differences (and similarities) between the environments surrounding these two film’s productions provides a very good setting in which to compare the films themselves and explore some of their contrasts and similarities. I have found that comparing two films (rather than analysing one) is the only way to effectively execute this dissertation, principally because it provides a means of limiting the amount of information at hand, as through comparison one film defines and distinguishes the other... without comparison this project would not be fit for an undergraduate dissertation, as it would require much more time and expertise than I am afforded here and would become far too flexible and subjective. There are of course some disadvantages in choosing these films as well, namely the lack of theoretical and academic work concerning either of them. While Carroll’s novel is the subject of countless academic works, most film adaptations have failed to warrant much consideration. Disney’s adaptation was not a commercial success and Walt Disney 4 Kotlarz, I. “The Birth of a Notion” in Screen 24/2 (March / April), p28 3 himself is quoted in numerous books stating Alice had “no heart”.5 It was also nothing new for Disney, animation or Alice as a text, hence it does not stand out in any particular way. It is referenced in many books for many reasons, though usually only in passing. Pruzhanskii’s Alisa is similarly scarce in academia, particularly that (those) written in English. There is relatively little information on Soviet cinema from this era largely due to state oppression, widespread apathy and helplessness of the people. However I am somewhat fortunate in that Kievnauchfilm, the studio behind Alisa, was arguably “one of the worlds leading animation studios”6 of its time and hence there is at least an adequate amount of information on Alisa (and Disney’s Alice) to carry out this dissertation. Furthermore, this project relies heavily on textual analysis and background information rather than in depth academic works on the films themselves. It is also important for me to acknowledge that comparing Alice and Alisa is complex and somewhat precarious due to their temporal and geographical differences. This dissertation will comprise of historical research and qualitative textual analysis, thus the issue becomes one of structure and forward planning in order to be able to address the relevant topics and gather the information necessary to effectively compare these films and their relative contexts. I will lay out my dissertation in the following manner: In the first chapter I will present my historical background research and cover the basics as it were. I will outline and review the basic plot and themes of Lewis Carroll’s novel, providing a general backdrop with which to review and analyse the films. It is important to recognize what aspects of the original book have been included and excluded from 5 6 Clarke, S. & Smith, D. Disney; The First 100 Years, p70 “Статья для ASIFA news” http://www.pilot-film.com/show_article.php?aid=16, (21st February 2008) 4 Alice and Alisa, and furthermore what themes have been elaborated upon, suppressed, and manipulated. Following this I will explore Walt Disney Productions, American cinema and to a lesser extent the social, cultural, political and economic state of the U.S. in 1951. Similarly I will look at Kievnuachfilm, the Soviet Union and its national and cultural cinemas in 1981. This information will provide the groundwork necessary to be able to properly and thoroughly compare Alice in Wonderland and Alisa in the Land of Miracles to each other and their respective circumstances of production. I have chosen to carry out this background and contextual research before the qualitative textual analysis because this will put me in a better position to analyse and comprehend the films effectively. “When we perform textual analysis on a text, we make an educated guess at some of the most likely interpretations that might be made of that text”7, hence there is a certain danger of subjectivity and flexibility due to the lack of ‘concrete evidence’ and presence instead of subtler, more hypothetical logic and deduction. This is a largely undeniable and inescapable element of textual analysis and theoretical work at large, however one can certainly take steps to combat and contain the potential for unsupported deductions. My preliminary contextual research will inform my textual analysis and give me an idea of what to look out for, and how to best conclude if Alice and Alisa reflect in no uncertain terms particular aspects of the environments in which they were produced. Hence, in the chapter following my background research I will first and foremost consider what, if anything, I have learnt about Disney, Hollywood, Kievnauchfilm and 7 McKee, A. Textual Analysis: A Beginner’s Guide, p1 5 Russia that might help direct my textual analysis and pinpoint certain potential key issues. This is not to say that my textual analysis will be biased by this information, but rather that it will make me more able and adept at assessing these films in relation to their circumstances of production. With this in mind, I will carry out my textual analysis of each film, focusing on the plot, characters, mood, themes, and style of animation of each film, and relating them to one another and the book to see what differentiates them all. Since I will focus solely on the texts themselves rather than how they might have been received by the masses, I can hence adopt a realist approach which presupposes there is a correct and incorrect way of understanding a text. Lastly, I will compare my findings and relate them to the respective contexts of production of Alice and Alisa in order to deduce if and how these contexts are manifested in the film’s themselves. 6 Chapter One: Covering the Basics ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND Since its initial publishing, the story of Alice has remained a popular, poignant text throughout the ages, consumed across the globe in a variety of mediums and adaptations. Written in 1865 by Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, better known by his pseudonym Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was first put to film in 1903 and has since been adapted to the stage, song, cinema and television, and is even referenced in medicine8 and economics9. It is still of interest to both adults and children alike with a new animated version by Tim Burton in pre-production at the moment. The story of Alice originated years earlier when Dodgson told three girls an impromptu story during a boat ride on the River Thames. This developed over the years into Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, a story of literary nonsense about a young girl named Alice who follows a talking rabbit down a rabbit hole into a ‘wonderland’ full of strange anthropomorphic creatures and bizarre paradigms and events. In order to properly understand Alice and Alisa it is important to consider how Carroll’s original text differs from and hence has been adapted and manipulated to suit Walt “Alice in Wonderland Syndrome” http://aiws.info/ (8 th March 2008) “Alice in Wonderland Economics” http://www.valleypatriot.com/VP060507drchuck.html, (9 th March 2008) 8 9 7 Disney Productions and Kievnauchfilm (though one must consider if such dissimilarities are intentional or possibly due to a genuine, alternative understanding of the book, of which there are many). Hence, a very brief literature review will follow: Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is a timeless tale that is themed largely on nonsense, imagination and the surreal. It deals with highbrow literary nonsense and language games, as well as exploring some mathematical laws and theories,10 all done in a very subtle, delicate manner that affords the book its intangible playfulness and excuses the otherwise bewildering events that occur in it. One of the most resounding messages that one may find in the book is that it is “good to dream”11, as the plot attests to, following Alice through what might be seen as her own ‘dream land’ where wonderful and enchanting events unfold. Another popularly conceived theme of the book is growing up, and maturing, which is presented through Alice’s changing in size continually, until she learns to control this with potions, cakes and mushrooms.12 However it is not in essence a story of morals, in my opinion. While there are many references to morals, ‘lessons’ and popular sayings for children throughout the book, Carroll does not concern himself with making sense, but nonsense. Much of the plot and peculiarity of the text is derived from (and hence only truly meaningful to) the personal and past experiences of Lewis Carroll and Alice, Lorina and Edith Liddell, (the three girls on the river with him that day). Kirk, D.F. “Charles Dodgson; Semeiotician” in University of Florida Monographs; Humanities no.11 (Fall 1962), p62 11 Ross, D. “Home by Tea-time: Fear of Imagination in Disney’s Alice in Wonderland” in Classics in Film and Fiction, p214 12 “Lenny’s Alice in Wonderland Site” http://www.alice-in-wonderland.net/explain/alice841.html, (2nd April 2008) 10 8 Due largely to the abstractness and nonsensical splendor of the book, it is very lighthearted and up beat, despite the sometimes cruel events of the plot. For instance, while the King and Queen of hearts continually have people beheaded, they do so in such an outrageous and entertaining way that the reality of the situation never worries the reader. The book is so far removed from reality and so calm, reassuring and matter-of-fact in its tone and manner that nothing could seem threatening (despite the sometimes threatening events), and everything instead seems as it should be, almost. Also, I should add, Alice is a very optimistic character, often finding the ‘silver-lining’ to any situation.13 Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is a very complex story, as it functions on many different levels to children and adults alike. It is a book of literary nonsense, yet there are many themes that can be taken from it. It is a children’s book, yet it is laced with mathematical and semiotic paradigms (Carroll was a teaching and practicing mathematician and semiotician)14 and appeals to adults around the world. However for the purposes of this dissertation I need only look at the text on a basic level, and largely as a children’s book. Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland consists of twelve chapters, the titles of which give a very, very basic idea of the structure of the plot of the book. Hence I will list and annotate these chapter titles below, and where necessary I will explain the plot in more detail in my analysis of the two films. Chapter One, ‘Down the Rabbit Hole’: Alice chases the White Rabbit ‘down the rabbit hole’ into a large hall full of doors, with one in particular that she cannot pass through. See, for instance; “And yet – its rather curious, you know, this sort of life!” Carroll, L. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, p34 14 Williams, S. & Madan, F. The Lewis Carroll Handbook, p x 13 9 Chapter Two, ‘The Pool of Tears’: After shrinking and growing due to potions and cake respectively, Alice cries a pool of tears which she then falls into after shrinking again. Chapter Three, ‘A Caucus-Race and a Long Tale’: Alice washes up on a beach, where a strange gathering of animals try to dry themselves by nonsensical means. Chapter Four, ‘The Rabbit Sends in a Little Bill’: Alice pursues the White Rabbit and gets stuck in his house, too large to get out. Eventually she removes herself. Chapter Five, ‘Advice from a Caterpillar’: She comes across a large dog, and then a caterpillar from whom she receives two pieces of mushroom that control her size. Chapter Six, ‘Pig and Pepper’: Alice enters a house where she meets the Duchess and the Cheshire Cat. The latter informs her of the Mad Hatter, and the March Hare. Chapter Seven, ‘A Mad Tea Party’: Alice converses with the Mad Hatter and March Hare, then finds her way back to the hall where the passes through the small door. Chapter Eight, ‘The Queen’s Croquet-Ground’: She finds herself in a beautiful garden, paints roses red, meets the King and plays croquet with the Queen. Chapter Nine, ‘The Mock Turtle’s Story’: Alice converses with the Duchess, who soon leaves. She is then sent off to meet the Mock Turtle with the Gryphon. Chapter Ten, ‘The Lobster Quadrille’: These two characters tell Alice a story in song about a lobster dance, then she is taken to a court room where a trial unfolds. Chapter Eleven, ‘Who Stole the Tarts’: A nonsensical trial ensues, whereby many characters stand witness until eventually Alice is called to the stand. Chapter Twelve, ‘Alice’s Evidence’: Eventually the Queen orders the beheading of Alice, who is much larger than everyone else at this point. The card soldiers flutter against her 10 and she wakes up on the riverbank with her sister. An end paragraph highlights the joys and wonders of childhood and imagination. 11 WALT DISNEY ANDAMERICA IN 1951 Disney’s 1951 Alice in Wonderland was produced in the years following the end of World War Two, at the beginning of the Cold War. For America, the 1950s “were a time of conservative politics, economic prosperity and above all, social conformity… Many look back upon the fifties with distaste and call it an uncreative and unidealistic time.”15 McCarthyism, the Cold War, and the open race for weapons of mass destruction sent the American public into a state of autopilot. Under the surface of everyday suburban life there was a climate of fear and confusion that few acknowledged. People were afraid of the threat from Russia, the possibility of communism in America and / or the possibility of being labeled a communist in America. Hence the public focused on simpler, more manageable issues such as family, church, the economy, and the so-called American dream. The result was a more plastic society where “appearance and acceptance had replaced inner values as guidelines to life”.16 The youth became alienated and popular culture followed suit, creating a plethora of films, books and songs that were in direct contradiction to the ideology of the time which sought to create the illusion that everything was wonderful. The world of film was also in a state of panic, confusion, and transformation due to the recent fall in cinema revenue and the advent of television into the average household.17 Cinema responded to this with technological innovation, challenges to censorship, wide screen formats, and more 15 Gordon, L. and Gordon, A. American Chronicle; Year by Year Through the Twentieth Century, p473-475 Gordon, L. and Gordon, A. American Chronicle; Year by Year Through the Twentieth Century, p474 17 Bordwell, D. Thompson, K. Film History; An Introduction, p328 16 12 colorful, visually stunning films than ever before in an attempt to “draw spectators out of their living rooms and back into theaters”.18 Many studios also began targeting specific audiences, such as children (Peter Pan in 1953) and the empowered youth “who had money to buy cars, records, clothes, and movie tickets”19 with films like Rebel Without a Cause (1955) in order to boost revenues and ensure success. Animation took a slight turn for the worse during the fifties which is largely considered the beginning of the critical decline of American animation.20 It was a fragmented and paradoxical time for America in many ways. “Since animation’s inception as big business in the early 1920s, several aspects of (Hollywood) cartoon production were purportedly at odds with the Soviet praxis.”21 From a very early age America saw animation first and foremost as a money-making enterprise rather than a form of art or entertainment, which hence dictated some of the finer points of American animation. For instance cel technology, once available, became the industry standard as it allowed for faster, cleaner and more ‘efficient’ animation through assembly lines and such. As a result of this “styles within any given studio had to be homogenized; the style of bigger, team-drawn objects had to be interchangeable … The suppression of individuality was an absolutely necessary mandate of Taylorism.”22 Technical skill, speed (particularly in the fifties where sequences were notably faster and more frantic) and homogeneity became the most important, defining characteristics of American animation. 18 Bordwell, D. Thompson, K. Film History; An Introduction, p328 Bordwell, D. Thompson, K. Film History; An Introduction, p325 20 “Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination” http://www.powells.com/review/2006_12_26.html, (30 th March 2008) 21 MacFadyen, D. Yellow Crocodiles and Blue Oranges; Russian Animated Film Since World War Two, p48 22 Crafton, D. Before Mickey; The Animated Film 1898-1928, p167 19 13 Disney by and large set the bar for American animation and defined the genre along side other would be multi nationals like Warner Brothers and MGM. Walt Disney Studios was founded in 1923 as a “modest two-man studio” and has since grown into “the international multi-media/merchandise giant that it is today.”23 It is in fact the third largest corporation of its kind in the world after News Corporation and Time Warner, it is a classic example of media convergence and cultural imperialism, and “it all started with a mouse.”24 Throughout the 1930s Walt Disney worked “to make Mickey (and, later, other characters created by the studio) either a daily or weekly part of people’s lives”25, and with much success. His success grew and grew as the company pioneered new cunning ‘business strategies’ in entertainment, for instance “a lawsuit from Walt Disney prevented (Lou Bunin’s stop-motion Alice in Wonderland) from being widely released in the U.S., so that it would not compete with Disney's forthcoming 1951 animated version.”26 Indeed most if not all of Walt Disney’s numerous enterprises have seemingly been somewhat suspect and unwholesome, as various books conclude.27 Nonetheless Disney Studios is also a ‘dream factory’ that has produced some magnificent work and branded itself with the values of “individualism, escape, magic, innocence and romance”28 to great success. “Understanding Disney; The Manufacture of Fantasy” http://www.cjconline.ca/printarticle.php?id=890&layout=html, (23 rd March 2008) 24 Walt Disney quote, see “Q & A Archives” http://imagiverse.org/questions/archives/disney1.htm, (24 th March 2008) 25 Smoodin, E. Animating Culture: Hollywood Cartoons from the Sound Era, p16 26 “Alice in Wonderland; By Lou Bunin” http://www.findinternettv.com/Video,item,552615244.aspx, (25 th March 2008) 27 See: Schweizer, P. & Schweizer, R. The Mouse Betrayed; Greed, Corruption, and Children and Risk 28 “Understanding Disney; The Manufacture of Fantasy” http://www.cjconline.ca/printarticle.php?id=890&layout=html, (23 rd March 2008) 23 14 Preceding World War Two, during the so-called golden age of animation, Walt Disney Studios was doing very well for itself, largely due to the success of Snow White and The Seven Dwarves (1938) which became the most successful motion picture of the year. Disney had come to represent ‘good old fashioned’ values and appealed largely to the middle class through notions of romance and morality. Also important to note is that Disney “had come to define animation as child’s fare”29 and the industry accepted this, and while Walt left scope for and indeed encouraged everyone to watch his cartoons, what is significant is that Disney labeled animation an endeavor primarily for children, which changed the way it was both produced and received. Animation was disregarded as a serious genre or medium for exploring adult themes and issues, and furthermore animated film was viewed with a sense of playfulness and childishness, which was not the case (relatively speaking) in many European countries, “where animation is a bold chance to explore artistic expression, and perhaps to entertain children.”30 Also worth mentioning, when talking about any American animation preceding the latter twentieth century if not later, are issues of misogyny and racial stereotypes. Disney was like most animation studios of the time in that it found it was allowed to represent “objectified female sexuality even to children (but only) as long as that representation conforms to accepted standards of racism and misogyny.”31 American media seems to have a well-established past time of misogyny and racism, though always presented (at least in the case of animation) as a joke, as something harmless and funny, as playful. Alice does not have any exemplary racial or misogynistic themes that I recall at present, 29 Smoodin, E. Animating Culture: Hollywood Cartoons from the Sound Era, p15 “Animation not reserved to Children” http://twitchfilm.net/archives/009301.html, (26 th March 2008) 31 Smoodin, E. Animating Culture: Hollywood Cartoons from the Sound Era, p24 30 15 but perhaps my analysis will prove different, particularly when comparing it to Kievnauchfilm’s Alisa. World War Two put a huge struggle on Disney as it was demanded they make propagandist, military animations to motivate and comfort the public. Many of the studios releases in the forties gave disappointing results, such as Fantasia (1940) and Dumbo (1941). However in 1950 with the success of Cinderella, “the Disney studio found itself in financial good health for the first time in more than a decade.”32 Although at the same time Walt Disney himself was getting unfavourable reviews from critics for “violating his own rules”33 by exploring the technique of pastiche (combining animation with live action footage) and furthermore by introducing more humanoid characters rather than his earlier established standard of anthropomorphic creatures. Even Cinderella was criticized for having too many ‘people’ in its cast (the three main characters being the witch, the prince and snow white). In this sense Alice surely provided a gleaming chance to ‘put right’ this move away from fantastical animals and furthermore reiterate the romance and wonder that Disney thrives on. Though it is not clear if Walt had any intention of doing so, as he was often documented publicly pushing for the studio to move into live action film making, moving toward reality, rather than away from it.34 Perhaps this turmoil between what Disney produced and what Walt wanted to produce accounts for its critical decline in the fifties. The 1950s was not, as much as people 32 Barrier, M. Hollywood Cartoons; American Animation in its Golden Age, p402 Smoodin, E. Animating Culture: Hollywood Cartoons from the Sound Era, p106 34 Eliot, M. Walt Disney, Hollywood’s Dark Prince, p209 33 16 wanted it to be, a happy, romantic, or wondrous time at all, and while many film makers acknowledged this, Disney seemingly tried to deny it. “In the light of the more sophisticated and adult work of the post-war period the Disney features with their sugary sweet sentimentality and slick, characterless drawing”35 seem unagreeable and out of place. Many of Disney’s productions from the 1950s such as Lady and the Tramp (1955) and Beauty and the Beast (1959), despite becoming classics, received mixed reviews at the time which perhaps reflects largely on the situation in America. There was in fact a critical decline in Animation in the 1950s due to “changing cultural attitudes toward such disparate subjects as genre, cartoon style, audience … and the development of television.”36 In a state of national anxiety a “suspiciousness enveloped American life”37, people were confused and a sharp paradox grew between the way people wanted to feel and the way they felt. 35 Kinsey, A. Animated Film Making, p13 Smoodin, E. Animating Culture: Hollywood Cartoons from the Sound Era, p104 37 Gordon, L. and Gordon, A. American Chronicle; Year by Year Through the Twentieth Century, p473 36 17 KIEVNAUCHFILM AND THE U.S.S.R. IN 1981 Comparatively, Ephrem Pruzhanskii’s 1981 Alisa in the Land of Miracles (АЛИСА В СТРАНЕ ЧУДЕС) was produced in the decade preceding the collapse of the Soviet Union, in a time of economic poverty, social recession and political instability. Under the leadership of Leonid Brezhnev, the strain of the arms race, and the invasion of Afghanistan, the economy floundered and the U.S.S.R. stagnated and withered.38 Brezhnev’s time in office saw a substantial increase in education, employment and quality of life although there was a growing health care crisis,39 and it was all at the expense of the economy and the dream of functioning Communism. He also led a reStalinization movement which, among other things saw an increase in repression of anything ‘anti-revolutionary’, including books and films.40 The public became suspicious and yet apathetic of the state as they were largely powerless, “most people spent their energies trying to make the best of a bad situation and were more interested in the entertainment programmes on television… than in politics”41 (which arguably inspired film-makers to really say something about what was happening to the country in their work). The film industry was in decline at the end of a more profitable and productive era, although some extremely artistic and powerful animations and films were produced in this period such as Skazka Skazok (1979) and Kievnauchfilm’s own The Tree and the 38 Lowe, N. Mastering Twentieth-Century Russian History, p378 “Commentary; The health crisis in the U.S.S.R., looking behind the façade” http://ije.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/35/6/1398, (22nd February 2008) 40 Dunlop, J.B. The Rise of Russia & the Fall of the Soviet Empire, p72 41 Lowe, N. Mastering Twentieth-Century Russian History, p387 39 18 Cat (1983). Lacking the capital to make grand, ‘block-buster’ films the U.S.S.R. instead produced short, insightful, artistic and intriguing cinema, such as Alisa.42 There are some very interesting similarities and differences to be found when comparing the Soviet Union and Kievnauchfilm in the 1980s to America and Walt Disney Productions in the 1950s. The U.S.S.R. was economically unstable and stagnant in contrast to America’s “back to the business of business”43 attitude in the fifties. This influenced their film industries as Russia was at a relative low point while Hollywood was on the up and up after its struggle during World War Two. There was also state interference in media and the repression of all things controversial or counter-productive in Russia, which carried the penalty of death in some instances, and exile in others. This remained the case up until the late eighties where under Gorbachev’s rule there was a brief “weakening of ideological and economic constraints”44 and some films such as Elem Klimov’s Proschanie (aka FareWell, released in 1986) were brave enough to directly challenged Soviet ideology.45 Politically, socially and culturally speaking the situation in the U.S.S.R. during its downfall was surprisingly quite similar in many ways to that of America in the early 1950s… Both nations were ‘living a lie’ to an extent, struggling to pretend that everything was all right, and in both cases this was due largely to the political situation of the time, though things were certainly more dire in Russia. This paradox translated “in “Alice’s New Adventures” http://context.themoscowtimes.com/story/174970/, (6 th December 2007) Gordon, L. and Gordon, A. American Chronicle; Year by Year Through the Twentieth Century, p473 44 Taylor, R. Wood, N. Graffy, J. & Iordanova, D. Eastern European and Russian Cinema, p5 45 Gillespie, D. Russian Cinema, p117 42 43 19 the (Soviet) cinema of the 1970s and 1980s (where) there is a yawning gap between public stance and private morality, between word and deed.”46 Culturally it was a creative time (as times of struggle often are) for both nations, although in both cases said creativity struggled to surface due to state repression and a lack of capital in Russia’s case, and fear, confusion and a ‘business before brilliance’ mentality in America’s case. Of course these similarities are somewhat dwarfed by the more fundamental differences that exist between these two ‘time-spaces’, differences between capitalism and communism, east and west, poor and rich... the 1950s and the 1980s. “The USA dominated the cartoon film world as it did the film world in general, although the Russians … also made their contribution.”47 It is not uncommon to hear the opinion that Soviet animation is, or was, or has been at times, the most beautiful and artistic animation in the world. Alisa’s parent company, Kievnauchfilm, was considered a truly great studio48 and a cultural symbol of Ukrainian and Soviet life,49 which can certainly also be said of Disney in America. The studio was founded in 1941 and all in all it produced 342 films before the fall of the Soviet Union, at which time it came under new ownership and was renamed the National Cinematheque of Ukraine.50 While it was primarily a studio concerned with documentaries and science films, Kievnauchfilm also turned out many animations that became infamous within the Soviet Union, making it the ‘Disney’ of Ukrainian and Soviet television, as it were, second only to Soiuzmul’tfil’m.51 46 Gillespie, D. Russian Cinema, p164 Kinsey, A. Animated Film Making, p13 48 “About this Video” http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6zh3C-D9KpQ, (26th March 2008) 49 “How to tell if you’re Ukrainian” http://www.zompist.com/ukraine.html, (22 nd February 2008) 50 “Kievnauchfilm (Kiev Science Film)” http://www.animator.ru/db/?ver=eng&p=show_studia&sid=94&sp=2, (21 st February 2008) 51 MacFadyen, D. Yellow Crocodiles and Blue Oranges; Russian Animated Film Since World War Two, xi 47 20 The state certainly had a hold over Kievnuachfilm as it did over most every media institute of the time (Alisa in fact opens with a message, “On Commission of the USSR State Committee of TV and Radio Broadcasting”), however this does not mean studios were required to produce happy, hopeful or otherwise optimistic cinema (like in America) as Soviet film and animation had a long established tradition of somberness, darkness and realism amongst more mawkish, Disneyesque productions which they also undertook. Under the guise of Soviet realisms “discomforting, potentially apolitical multiplicity” Soviet animation became very flexible, exploring both very dark subject matter while also being “reticent, humble and happy.”52 There was “an intriguing divergence that emerged between Russian and American cinema in the years 1913 and 1914”53 whereby Russian film, and its film goers came to embody a much more somber, realistic and uncensored representation of things, while Americans would not accept anything other than ‘happily ever after’. “In fact, films that were exported from Russia to America just before the war, and many since, had their endings tailored positively to make them appeal to American audiences.”54 This ‘divergence’ continued throughout the twentieth century and paved the way for the sharp dissimilarities that exist between American and Soviet animation. American film and animation has the aim of (and need for) profit at its forefront, while the Soviet film and animation industries, due to the nature of communism, are afforded more artistic and individual freedom, hence soviet media is in some ways much more flexible and 52 MacFadyen, D. Yellow Crocodiles and Blue Oranges; Russian Animated Film Since World War Two, p4 & 27 respectively. 53 Cousins, M. The Story of Film, p49 54 Cousins, M. The Story of Film, p50 21 adventurous than that of America. Animation in the U.S. was built on a formula of technical brilliance, bright stereotypical characters and eventual happiness, which it followed very closely, and still does, whereas Soviet animations differ from one to the next in terms of the style and technique of animation used, the mood and themes of the text and the conclusions drawn at the end of it. Film and animation from the U.S.S.R. are more willing to explore technical, thematic and stylistic possibilities, as are its audience. These differences between the two national approaches to animation are perhaps also due to cultural and ideological differences between the two nations and technological and stylistic preferences / capabilities. 22 Chapter Two: Alice versus Alisa A BRIEF WORD ON TEXTUAL ANALYSIS Textual analysis is a methodology, but it is not a science. A methodology may imply to some a “standardized procedure that doesn’t require any creativity or originality, a … recipe that anybody can follow and come up with the same answers every time. Textual analysis isn’t like that.”55 The textual analysis involved in this dissertation is relatively straightforward, though thorough, as it deals solely with the actual texts themselves rather than considering, for instance, how they were received, how the actors and directors achieved what they did and whether this was their intention, etc, etc. While these issues might arise, they are not the necessary focus of my analysis. In short, and to reiterate, I aim to analyse Alice and Alisa in order to explore if or how the information presented in chapter one might lend itself to better understand the differences between these two films. I will approach my textual analysis with no foregone conclusion in mind, I am open to whatever the text’s may tell me, and furthermore I will aim to be as precise as possible and only make statements which are supported by the evidence. First and foremost I will present a brief analysis of each film separately (though often referring comparatively to the other, as was done in the previous chapter when reviewing America and Disney in the 55 McKee, A. Textual Analysis: A Beginner’s Guide, p118 23 1950s and the U.S.S.R. and Kievnauchfilm in the 1980s) where I will review fundamental aspects of the texts such as their atmosphere, plot, characters, visual style and themes. Following this I will carry out a more comparative, in depth analysis that will incorporate the information presented in chapter one in order to explore the thesis of this dissertation and draw some conclusions. 24 ALICE IN WONDERLAND Disney’s Alice “premiered in England on July 26th, 1951, and released in the U.S. two days later.”56 It was directed by Clyde Geronomi, Hamilston Luske and Wilfred Jackson and was nominated for an Oscar for ‘Best Music, Scoring of a Musical Picture’ in 1952. Walt had been meaning to make a version for decades, first considering a live-actionanimated version in the 1920s.57 After numerous obstacles and upsets, Alice was produced, although Walt was unhappy with the result, as were critics. “Alice was a frantic film… Everyone working on it seems to have suffered from discomfort with the material, bordering on panic.”58 Furthermore, during the film’s production Walt is said to have shown a “continuing lack of personal involvement … and inattention to its production.”59 The film was not a commercial success until rediscovered by the counterculture movement of the sixties, at which point it was hailed as a psychedelic masterpiece. Since then it was re-released in 1974 and 1981, released on video in 1981 and 1986 and kept in release”60 ever since. It is now considered a cult classic in some circles and the most popular film adaptation of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland to date. Technically speaking Alice was ‘superb’ for its time, as are almost all of Disney’s feature length animations.61 Throughout the twentieth century the Disney studio revolutionized 56 Smith, D. The Official Encyclopedia; Disney A to Z, 3rd Ed., p19 Eliot, M. Walt Disney, Hollywood’s Dark Prince, p23 58 Barrier, M. Hollywood Cartoons; American Animation in its Golden Age, p55 59 Eliot, M. Walt Disney, Hollywood’s Dark Prince, p209 60 Clarke, S. & Smith, D. Disney; The First 100 Years, p20 61 Kinsey, A. Animated Film Making, p13 57 25 the industry with inventions such as the “huge vertical racking system”62 constructed for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) which achieved unparalleled visual depth. Alice utilizes this racking system, and was composed using the industry’s standard hand drawn cel animation that was largely informed by live actors playing out the scenes of the film.63 Using actors to inform animation is again something that Walt Disney introduced to the industry as a result of his aforementioned desire to make more realistic (and eventually live action) films. Alice is also a quintessential example of the visual creativity (and hence psychedelic acclaim) of Disney animation, as can be seen for example at the beginning of the Walrus and the Carpenter sketch (which does not appear in the book at all) where the round heads of Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum (who are also absent from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland) become the sun and the moon where night and day are side by side, separated only by a line down the middle of the ‘set’ (15:30). The sound and scoring for the film was a huge selling point, as the 1951 trailer attests to by literally listing the songs and referencing the “wonderful tunes” as a high light of the animation. This aspect of the film was seemingly a success as it warranted Oscar nomination as aforementioned. In relation to the plot, Disney’s interpretation of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is not particularly true to the original text, and seemingly adopts a somewhat ‘cut and paste’ approach to Carroll’s classic. It is a highly stylized, shallow rendition of the original story whose chief priority is fluidity and transition. Thus Disney’s Alice loses much of the 62 Cousins, M. The Story of Film, p166 “Kathryn Beaumont” http://www.alice-in-wonderland.fsnet.co.uk/film_tv_disney2.htm, (20 th February 2008) 63 26 meaning and significance of the original story and its plot developments. For instance, in the book when Alice is stuck in the White Rabbit’s house and Bill the lizard attempts to enter through the chimney to remove her, Alice, with “one sharp kick”,64 stops Bill by force, thus empowering her and giving Alice control over her own actions and the situation. Disney, however, reconstructs this scene, whereby Bill is defeated by Alice sneezing (a somewhat clumsy and certainly uncontrollable action) him out of the house due to chimney dust. This is an example of how Alice’s successes and intentional, autonomous actions found in the book are replaced throughout the film by incidental mechanisms, thus disempowering Alice a great deal. This treatment of Alice is intentionally furthered in the addition of completely new plot that was written by the studio for the film. I am referring in particular to the scenes following the tea party, in which Alice becomes lost in a strange forest full of strange creatures and begins to sing ‘Very Good Advice’ (54:26). One of her lyrics in this song, “I should have known there’d be a price to pay” clearly presents the audience with a moral of the film (which is not to be found anywhere in the book), that the reality of a ‘wonderland’ is not so wonderful, and that imagination and curiosity can get you in trouble. Disney reinforced this message by making Alice openly ask directly for what she gets (and does not enjoy) in Wonderland while on the river bank at the beginning of the film… talking cats and flowers, ‘nothing would be what it is’ and so on, thus inciting the old moral, ‘be careful what you wish for’. In this sense Disney’s Alice becomes (at least in relation to the original text) an example of “a text which examines and inverts a social 64 Carroll, L. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, p38 27 ideological paradigm.”65 Furthermore, the added story line arguably changes the message of the whole text as it conclusively choreographs the break down and admitted defeat of Alice.66 While the book generally presents Alice as empowered and content in her decision to follow the white rabbit into wonderland, Disney’s rendering of the text does the opposite, turning wonderland into a barefaced nightmare by the end of the adventure. Much of the plot-manipulation seems senseless, as it achieves nothing but to replace what should have been with what should not. For instance chapter six, ‘Pig and Pepper’, which involves the Duchess nursing a pig as if it were a baby whilst having a cook throw “everything within her reach at (them)”67 was excluded from the film, while a walrus coaxing and then eating a family of endearing anthropomorphic oysters (which again I must point out is not in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland) was presented in song and dance. In fact the Duchess does not appear at all in Alice, as is the case with the Gryphon, the Mock Turtle, and the story of the Lobster Quadrille. These omitted characters and events are replaced largely by characters and events that exist in Carroll’s sequel to Alice, Through the Looking Glass, and What Alice Found There (1871). Hence Alice becomes more of an ode to Carroll than to Alice, as Disney has selected its own favourite pieces of the author’s work and strung them together using the frame of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Carroll’s work lends itself quite nicely to this possibility as it is all literary nonsense and as aforementioned largely without meaning, hence there is not too much consequence in replacing one nonsensical event with another. These many changes to Stephens, J. Language and Ideology in Children’s Fiction, p139 Ross, D. “Home by Tea-time: Fear of Imagination in Disney’s Alice in Wonderland” in Classics in Film and Fiction, p218-219 67 Carroll, L. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, p62 65 66 28 Carroll’s classic text are largely a result of (Walt Disney’s) personal choice and an attempt to optimize the fluidity and marketability of the film… to make money. As aforementioned Disney’s treatment of the heroine, Alice, is very different and much less kind to that of the book. Alongside her being disempowered and defeated, and perhaps as a consequence of it, Alice is also too ‘prissy and ‘passive’68 (Walt Disney himself said this). Her reactions to the outrageous characters and events that surround her are far too calm, controlled, and empty. It is hard to pinpoint a specific instance in the film that epitomizes this passiveness as it is more of a continual disposition illustrated by Alice’s every move and persistently plastic smile and manner. This submissiveness becomes greatly more apparent when she is compared to the curious and engaging Alisa from Alisa in the Land of Miracles. On the Disney Alice in Wonderland DVD there is a bonus feature in which Walt Disney introduces to the camera Kathryn Beaumont, the voice of Alice. She was largely taken as the literal inspiration for Alice in the studio as she was made to act out all the scenes, dress the part and so on. However Kathryn Beaumont was, or at least appeared to me from the very outset to be a shy, passive and prissy girl… no wonder then that Alice turned out as she did. Perhaps this choice for Alice was a result of “the post-war concern that America’s women should return to their pre-war domestic subservience.”69 Graphically speaking, Disney’s presentation of the characters of Wonderland is very accurate to the original, and still most popular illustrations for the book by John Tenniel. 68 Schickel, R. The Disney Version, p295 Allan, R. “Disney’s European Sources” in Girveau, B. Once Upon a Time: Walt Disney, The Sources of Inspiration for the Disney Studios, p160 69 29 However, almost all of the characters in Alice seem inexplicably cruel and / or psychotic (which is not at all the case in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland). While the singing flowers (who do not exist in the book) fall into the former category, continually teasing and condemning Alice, Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum are an example of the latter as they move about far too violently, both physically and emotionally speaking (13:45). Any kind or agreeable characters of the film, such as the collection of animals that take part in the caucus race on the beach (which has a whole chapter dedicated to it in the book) are dismissed as quickly as possible, while any characters and scenes that create conflict have been fully featured or even drawn out. This abundance of heartless horrid characters and interactions, I believe, is not intentional, but an illustration / consequence of the struggle and ‘panic’ that Walt Disney and his production team experienced when making the film. Alice was not marketed as frightening or nasty in any way, and it is completely uncustomary of, and illogical for Walt Disney Productions to produce such a film, thus I conclude that this malice is largely unintentional, as the evidence suggests. While the Cheshire cat is friendly and warm toward Alice, he ultimately orchestrates her downfall and near beheading. The Mad Hatter and the March Hare are both too insane to establish much of a relationship with Alice, although they do laugh at her (43:35) and ‘taunt’ her with tea, as it were. The only reasonable, thoughtful, or otherwise helpful character in wonderland, in my opinion, is the Caterpillar. He speaks to her, albeit in a very demanding and authoritarian manner, though still listening to her and trying to understand her situation. His last “helpful hint” (36:17) is one that allows Alice to gain control over her size (which is one of the key struggles throughout the film) by eating pieces of mushroom. 30 In fact my analysis has led me to believe that the caterpillar scene is somewhat exceptional and unique for a number of reasons… In the moments preceding Alice’s encounter with the Caterpillar, while she is wondering through the forest, the artwork of the film almost completely changes in a beautiful, bright shot that is much more fitting of wonderland (31:53) than any other in the film. This style of set animation continues throughout the caterpillar scene (and lingers to an extent throughout the following scenes) and seems to create a perfect atmosphere for the retelling of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Indeed, this scene is perhaps the only one that truly seems related to the original text and the mood and atmosphere that it envisaged. While a lot of the film seems confused and unsuccessful at expressing what it aims to, here Alice and the Caterpillar both become functioning, acceptable adaptations of the Alice and the Caterpillar found in Carroll’s classic text. The Caterpillar scene, its artwork and its musical accompaniment are also the most foreign and unconventional to be found in the whole of Alice. Perhaps, or even probably, this is simply coincidence, though critically speaking it suggests that a possible cause of Alice’s awkwardness (and relative critical and financial failure in its time) is Disney’s blatant attempt to standardize, Americanize, and make sense of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, which was intended to be unconventional and outlandish. Whatever the reason, the caterpillar scene is a uniquely carrollesque feature of Alice. The mood and atmosphere of Alice is quite erratic. At times it is briefly fantastical and exciting, though mostly it is bewildering, tiring and dark due largely to the hostility Alice 31 encounters in Wonderland, and the imagery that surrounds it. Many visual aspects of the film are somewhat subliminally (and seemingly unintentionally) sinister and invasive despite their sugary glossiness, for instance the black, endless ocean and dark skies that threaten Alice when she is floating in an empty bottle (11:36), or the general blackness that almost every background fades into, as though wonderland were some kind of eerie, underground mad house. Disney’s depiction of wonderland (and its characters, as I have discussed) is much darker and more sinister than Carroll’s, which does not seem to make sense, coming from a producer of sugary, cute children’s animation. This darkness, I suppose, is a necessity in order to validate Alice’s desire to ‘go home’ and hence the cautionary theme that imagination and curiosity can have unpleasant consequences. The negativity of the characters, the atmosphere, and Alice all comes together in this sense, as one resoundingly pessimistic portrayal of wonderland. It seems very strange that Disney would choose to make such a negative film, and perhaps explains the panic and discomfort that allegedly everyone working at Disney experienced with regard to this project. Thus, the stylistic, simplistic, sugary nature of American children’s animation clashes with Disney’s negative interpretation of Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, producing a film that, while capturing some of the beauty and splendor of wonderland, also seemingly highlights all of its potential darkness and desolation. This intentional thematic negativity of Alice is sharply contrasted by the endearing and comical silliness that lies on the surface of the film (and all things Disney), which creates a very psychologically eerie and uncomfortable pairing of genuine childish cuteness and 32 menacing dogmatic cynicism. Even during the acclaimed musical scores of the film such as “Golden Afternoon” (27:28) there is a certain underlying emptiness and strangeness that is quite discomforting and disturbing. Furthermore, immediately after welcoming Alice and singing to her, the flowers turn on her, teasing and taunting her. One academic concluded that “the Alice in Wonderland of 1951 loses something of the dark tranquility of Carroll,” and instead is “frantically American… bombastic and anarchic, which in its own way returns us to Carroll’s dangerous tranquility”70, though in a much more sinister and intruding manner. Alice is presented to us under the pretense of being a standard, endearing, cute Disney animation, and yet this ‘cuteness’71 is contrasted and adulterated by surprisingly dark and troubled overtones. Alisa is also a rather dark animation (both literally and metaphorically speaking) though it is such on purpose, consciously and intentionally. There is a sharp and telling difference between the way that these two films represent and utilize the darkness of wonderland, as I will later discuss. The most striking theme of Alice in Wonderland is considered by many to be ‘surreality’, psychedelia, and madness. However Alice was made for children, thus what for the many adults who enjoy the film seems to be psychedelic and surreal for children it would simply seem magical and strange. A more purposeful, evident theme is that of manners and education, which can be seen for instance in the way Alice interacts with Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum (13:50), the Mad Hatter and the March Hare, or the Queen, as Alice courtesies for her and tries to handle herself as politely as possible. This theme is Allan, R. “Disney’s European Sources” in Girveau, B. Once Upon a Time: Walt Disney, The Sources of Inspiration for the Disney Studios, p130 71 Schickel, R. The Disney Version, p174 70 33 true to the book and its many recitations,72 references to etiquette, and word and thinking games, though seems to develop and integrate it into the whole film, making it a more purposeful and notable element of Alice. This theme is also particularly significant, both to America in the 1950s (which I will discuss later) and as it provides another reason for the film and Alice’s ‘plasticness’ and passiveness. Furthermore, it is worth noting that Alisa (of Alisa in the Land of Miracles) is not half as polite, passive, or indeed plastic. There is also the aforementioned predominant ideological theme that curiosity and imagination are dangerous and must be controlled, which is used as a segway to the more common theme of ‘there’s no place like home’ (which is clearly established when Alice tells the Cheshire cat “I want to go home!”(56:26)). This piece of dialogue is symbolic of much of the film and its defeated, queer and uneasy nature. 72 Carroll, L. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, p14 34 ALISA IN THE LAND OF MIRACLES Ephrem Pruzhanskii’s adaptation of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was released on Soviet television in three parts over the span of 1981. In total it has a run time of only 30 minutes. As aforementioned, Alisa is a largely unreferenced and overlooked film despite its beauty, poignancy and popularity in its day. It is certainly not a main-stream film outside of Russia, though it still has its success, for instance it was voted one of the ‘best movies’ of 1981 on one website73 and cited as the best animated version of Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland ever on another.74 Alisa is a fine example of darker, more mature Soviet animation in that it is artistic and dreamlike, appeals to children and adults alike, and often deals with quite adult themes through symbolism and metaphors. Furthermore it is insightful and considerate in its handling of Carroll’s original text, acknowledging within the first minute that “everything in it is like in a fairy tale, and yet it doesn’t look at all like a fairy tale” (00:50). From what I have gathered from conversations with people who lived in Russia in the 1980s, Alisa was on Soviet television quite often and was a well-known (and arguably well-liked) animation.75 It is still in circulation today through various Internet resources and is also available on DVD. So, to follow in the footsteps of my analysis of Disney’s Alice, technically speaking Alisa is of a relatively high standard, as were many Soviet animations from “the Brezhnevite “Best Movies of 1981” http://www.mysubtitles.com/index.php?movies_from_year=1981&index=0, (17 th March 2008) 74 “A good sledgehammer strike of a cartoon” http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0211191/, (23rd February 2008) 75 Circumstantial evidence from Vadim Urasov and Maria Shvedunova. 73 35 era.”76 It uses standard hand-drawn animation on top of what appears to be watercolor backgrounds, and also utilizes cutouts and different textures (as can be seen for instance in the hair of the white knight77), and certain special effects on occasion, such as superimposition (03:21). Much of the animation is extremely abstract and surreal, as can be seen for instance when Alisa is falling through ‘the middle of the earth’ (02:48). Here the animation style seems similar to Japanese anime in its metaphorical and symbolic imagery. Examples of the ‘surreality’ of Alisa can be found throughout, though perhaps particularly notable in the presentation of the glass table (06:15) the forest near the March Hare’s house (13:34). Furthermore there is a tangible, crude element of sinisterness in much of the imagery (and colour scheme), for instance ‘do gnats eat cats?’ (03:33). Most every “voice delivered (in Alisa) goes from a talented actor or actress”78 and its soundtrack is very engaging and appropriate as it incites fitting atmospheres for many of the scenes, such as the introduction on the Cheshire Cat (12:00) and the madness of the croquet scene (17:43). Alisa, as aforementioned, is very considerate in it’s retelling of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and as such is quite faithful to the original plot and story line, or at least as much as in can be in the space of 30 minutes, following the order of events almost exactly. After the hall full of doors (04:31), Alisa wanders straight into her exchange with the Caterpillar atop the mushroom, thus omitting chapters three and four. From here the plot continues as it should with Alisa meeting the Cheshire cat (referred to as ‘dear “Алиса в Стране Чудес, мультфильм, 1981” http://jabberwocky.ru/alisa-v-strane-chudesmulmztfilmzm-1981.html, (29th March 2008) 77 “Алиса в Стране Чудес, мультфильм, 1981” http://jabberwocky.ru/alisa-v-strane-chudesmulmztfilmzm-1981.html, (29th March 2008) 78 “A good sledgehammer strike of a cartoon” http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0211191/, (23 rd February 2008) 76 36 Cheshire Puss’ (12:03) in accordance with the book79), and from there she meets the Mad Hatter and March Hare, thus skipping chapter six much like Alice does. Alisa further excludes chapters nine and ten, leaving the rest of the story in tact and accurately portrayed, with one or two small exceptions. For instance, while in the book the gardeners are painting a white rose bush red80, in Alisa they paint a red rose bush white (16:06). Such an inaccuracy in a film that is otherwise so accurate must be intended as meaningful. While this cannot be taken as fact, I would argue that red (symbolizing the State of Communist Russia) being covered by white (typically symbolic of purity, peace or hope) is a metaphor negating the government and espousing hope and peace. Alisa in the Land of Miracles is not only accurate in a broad sense, but also in its attention to many smaller details and dialogue from the book. For instance Alisa lands in a “heap of sticks and dry leaves”81 after falling down the rabbit hole, and then enters a hall with many doors (as it is written in the book), where as Alice lands upside down hanging from a curtain rail by her toes like some kind of casual acrobat (07:08), and then enters an empty hall, save the one, tiny door that is necessary to the plot. Alisa is also narrated, which allows it even more direct use of and similarity to the book (particularly in expressing the feelings of the characters, which hugely impacts what is said and done). In being this representative of and similar to the original text, Alisa expresses the same over all theme of the book; that it is good to dream, imagine and inquire. Indeed Alisa seemingly promotes this theme more intently than the book itself through its overly optimistic and empowering treatment of the main character and the ending of the film, Carroll, L. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, p66 Carroll, L. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, p84 81 Carroll, L. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, p5 79 80 37 which endorses the dream of wonderland and delight of being young at heart (taken from the book). The fact that Alisa is such a short film means that its creators have had to select which events of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland are the most significant and definitive to their understanding of the book (or the understanding of the book that they have chosen to present). And indeed I find their choice of content to be superb in this respect, as almost every scene and piece of dialogue is justified and epitomizes some theme or mood. Between the Caterpillar, the Cheshire Cat, the Mad Hatter’s tea party and the croquet and court scenes, Alisa is able to capture beautifully the essence of this story, while also manipulating the text to its own ends. In choosing the Caterpillar sketch for example, Alisa is given a chance to express the unconventional, nonsensical wisdom and logic of Carroll’s novel as well as the caterpillar himself, a magnificent and iconic character of the text. The film is somewhat wayward with this scene, although only because it has to be, I believe. “Language in Soviet animation was often downplayed to a minimum”82 and furthermore Alisa was made with a limited budget and runtime, thus rather than wasting several minutes of dialogue, they wrote some of their own which captures well the grand thinking and mind frame of the book. This extra dialogue went hand in hand with Kievnauchfilm’s kinder and more caring rendering of the Caterpillar (who they have presented as female, while in the book it is simply genderless), who explains to Alisa, “you see, everything’s moving somewhere and turns into something” (10:50). This statement, and furthermore the way it is delivered, is quite simple and 82 MacFadyen, D. Yellow Crocodiles and Blue Oranges; Russian Animated Film Since World War Two, p47 38 serene and yet insightful and enjoyable, which I find to be in the same taste as the book in many ways. It also touches on the theme of physical and temporal growth and maturity, relating to the book. The ‘Mad Tea-Party’ is a scene which allows Kievnauchfilm to present the very adult theme of psychosis and dementia. Like the Caterpillar scene, and indeed most every scene in the film, it has been shortened and broken down to its essential mood, message and meaning. Hence the Mad Hatter and March Hare are both very worrying, clinically ill characters that bear more resemblance to a vampire and a hard drug addict (respectively) than the comically silly profiles found in both Disney’s Alice and the original illustrations for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by John Tenniel. Alisa certainly adjusts many of the characters as I will go on to demonstrate, not so much changing them completely as highlighting particular aspects of them. The Mad Hatter is a thin, tall, and extremely pale character with a deep, thick voice (truly reminiscent of the stereotypical Count Dracula), while the March Hare is similarly pale and continually shakes, shudders, or fidgets, wrapped in a blanket with his eyes darting about. To capture the essence of the scene and these characters as re-imagined by Kievnacuhfilm, Alisa utilizes the following dialogue: Alice: “I know I have to beat time to play music.” [Clock’s chime, Mad Hatter and March Hare shiver with fear] Mad Hatter: “He wont stand beating!” March Hare: “Yes, We quarreled with time.” Mad Hatter: “It’s always six o’clock now. And it’s always tea-time.” March Hare: “We even have no time to wash the cups between whiles.” (15:14) 39 While textually speaking this is quite similar to how it appears in Carroll’s Alice, there is a vast difference between how the two texts present and express these words. While in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, with the aid of Tenniel’s illustrations and small hints from Carroll (such as the Mad Hatter pointing with his teaspoon, and the March Hare sighing) we know that this dialogue is spoken in a casual, though disappointed and slightly sorrowful tone, whereas in Alisa this dialogue is spoken with real anxiety and frustration, as if from the mouths of actual, clinical schizophrenics. Both the Caterpillar scene and the Mad Tea-Party are examples of how Alisa illuminates upon many of the more adult themes and aspects of Carroll’s book. The ‘Tea-Party’ is furthermore an example of some of the intentional, and artistically rendered menace and darkness of Alisa that I alluded to in my analysis of Disney’s Alice. There is no dismissing the very realistic illustration of madness and psychosis found in this scene, which is in step with the realism of Soviet animation and culture. Kievnauchfilm’s “invisible… internal” realism that captures so well the maturity and truth of wonderland (which follows in the acclaimed style of the socialist, soviet realist art movement) is very different to Disney’s “naturalistic”83 and factually informed visual style (which has been widely criticized and badly received). These relative forms of realism surprisingly speak largely to the relative success and nature of Alice and Alisa: Disney’s Alice was animated with continual reference to real people, animals and landscapes (which it was criticized for), and partially as a result of this it is unintentionally eerie and seems uncomfortable in 83 MacFadyen, D. Yellow Crocodiles and Blue Oranges; Russian Animated Film Since World War Two, p36-37 40 itself, whereas Alisa, with its outrageously abstract backgrounds and characters (visually speaking) seems more realistic, mature and successful in its intentions than Alice ever could. Another theme of Carroll’s that is picked up on in Alisa (though quite sleepily, if you will) is that of morals. This again is illustrated through one particular scene and character, this time it is the character of the Duchess leading up to the trial (20:53). This scene is particularly true to, and hence takes most of its dialogue and other instructions from the book. It is too simple and straightforward in its rendition of things to have any purpose other than to capture the nonsensical silliness of Carroll’s book. The last key theme of Alisa, one that rings loudest and clearest to me, is that of bureaucracy, uncontrolled power, and the idiocy of ‘the system’. These issues all play out through the Queen and her part in the croquet game and courtroom. First and foremost, to discuss the representation of Kievnauchfilm’s Queen, she is presented as a spoilt, selfish individual that always gets what she wants… which of course she is, however while Disney’s Queen is a fat, extremely loud and enraged woman at all times, Kievnauchfilm’s Queen is thinner, snootier and more ‘bitchy’ (to use the parlance of our time). Kievnauchfilm’s Queen is intentionally laughable and immature, hence making her less imposing and arresting to the audience, while Disney’ Queen is a genuinely scary, worrying woman. While the book itself clearly raises issues of bureaucracy and abused power, Alisa makes these themes its own through certain key discrepancies and alterations to the original text (such as the aforementioned roses). During the Croquet game the Queen becomes quite 41 frantic and overwhelmed, shouting in the manner of a very upset little girl on the verge of tears, “off with her head! Off with his head! Off with that head, too!” (18:07). This is very different to Disney’s Queen, who is much more overwhelming and empowered. This difference between the two films grows in the courtroom scene where, while Disney presents a very threatening and menacing situation, Alisa is more concerned with making fun of the Queen, her bureaucracy and her pack of cards, thus empowering both Alisa and the audience. The executioner is presented as a small, useless figure covered from head to toe in a red sheet. He is ordered to behead the Cheshire Cat and thus pulls out his axe, which in fact is a balloon that he blows up and then sharpens (18:47), never actually using it (this has no basis in the book). In this sense the executioner, through imagery, is presented as impotent and feeble. This scene utilizes Carroll’s atmosphere of nonsense and silliness to make a fool of the executioner (and everything he might represent to Soviet society, dressed completely in red). More notable discrepancies are found in the courtroom. For instance the White Rabbit slyly, coyly creeps around the Queen’s chair (who sits as judge, of course) whispering to her what should happen, and how, and then gets “scared of his own audacity. To say no the Queen herself!” (23:56) and some very dark imagery ensues of the rabbit’s top hat falling from the executioners chopping block. It is worth mentioning that the events of chapter eleven, ‘Who Stole the Tarts’, as expressed in the book are quite jovial and quarrelsome, not inciting at all the intensity and symbolism found in Alisa. While on the stand, the Mad Hatter says, “I keep thinking of the bygone days” (24:41), which while related loosely to the book manipulates the sentence to take on a whole new meaning of 42 social criticism in this film. Next, the March Hare takes the stand and is ‘suppressed’, at which point the narrator explains how “Alice had read in the newspapers: ‘The attempts at resistance were suppressed.’ Now she understood what it meant.” (25:35). Carroll had written “there was some attempt at applause, which was immediately suppressed”84. The difference is clear, and its impact similarly so. The White Rabbit continues to direct the Queen and everyone follows suit as meaningless evidence is manipulated to justify the persecution of the Knave of Hearts. Eventually the Queen turns on Alisa, to which our heroine says, “You’re nothing but a pack of cards!” (28:42). I will explore the potential explanations for these discrepancies and their meanings in the following subchapter of this dissertation. Thus, despite its obvious consideration for the text, Alisa is by no means a carbon copy of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. By and Large Kievnauchfilm changes many of the characters to differentiate them from one another and thus utilize each one to present a different theme or facet of the story. Alisa is generally darker than the book (which as I have explained cleverly avoids the dark reality of its content almost completely) though I would argue not as sinister or unsettling for its audience as Disney’s Alice. Due to Alisa’s abstractness, and the wonderment and fortitude of Alisa as a character, the film is somewhat successful at emulating the books previously discussed subtle and delicate manner (while Alice is not), thus Alisa is largely empowering and intriguing to its audience, not bewildered or threatening like Disney’s Alice is. 84 Carroll, L. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, p127 43 Another dissimilarity between Kievnauchfilm’s Alisa and Disney’s Alice is their relative treatment of the heroine of the text. While Alice manipulates the text in order to disempower and pacify her, Alisa instead omits any of her inherent weak moments, such as her crying (which occurs throughout the text), thus making her braver, stronger and less prissy than the book originally envisions her. This contrast is also evident from a narrative perspective, as Alisa chooses scenes and events where the heroine is the most engaging, interested and active. For instance, Alisa uses the pieces of mushroom to get through the tiny door that troubles her in the beginning of the story, whereas Disney’s Alice cries and complains until the Cheshire Cat presents her with a passage to the Queens garden. Similarly, once in the garden Alisa saves the card gardeners from being beheaded (17:17) (as it is in the book) while Alice does nothing to save them, and hence they are dragged away to their deaths (61:01). This difference, again, is one that I will elaborate upon in the following section of this dissertation. One consideration I must make is that of the language barrier between Carroll’s English of 1865 and Russian in 1981. I am not afforded the time or resources to thoroughly explore the Russian translation of the book by N. Demurova, though from what I have gathered it is perhaps “less artistic, but very close to the original text in spirit, with all of its linguistic reversals and parodies.”85 I believe this translated version was taken as the basis for the film, and as I cannot explore the small discrepancies that might exist between the translation and Carroll’s original, I must assume for the sake of this dissertation that the two books are by and large identical. “Алиса в Стране Чудес, мультфильм, 1981” http://jabberwocky.ru/alisa-v-strane-chudesmulmztfilmzm-1981.html, (29th March 2008) 85 44 DO THE PIECES FIT TOGETHER? I have thus far hinted at and loosely discussed certain national, temporal, and other explanations for the discrepancies between these texts, though much of it is somewhat messy, jumbled and overlapping, hence I will now try to clarify, distinguish and develop certain key aspects of my analysis and draw some more appropriate and significant conclusions from my findings. Firstly, there are many basic deductions that can be made to explain certain elementary aspects of these two films. For instance, Alisa in the Land of Miracles is largely an exemplary piece of Soviet animation of the 1980s, as can be discerned by its use of realism, abstractness, adult themes and social and moral significance. It is short due to the economic draught of the early eighties in Russia, though still a very poignant and expressive piece of film, as is the nature of Soviet film and animation. Similarly, Alice in Wonderland has many attributes that liken it to the formulaic, glossy production-line animation of 1950s America. Its depiction of characters and events appears at least on the surface to be very Disneyesque and its impressive catalogue of musicals and songs suggests it is from a financially fruitful time (as increasingly was the 1950s for Walt Disney Productions). While there is the obvious and largely useless conclusion that Alisa is identifiable as a product of Russian animation, and Alice one of American animation (which has already been applied throughout much of my analysis), there is also much more interesting and complex information that has come out of this study thus far. Information and issues that 45 relate to social, economic and political circumstances among other things. In comparing the many ways that Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland has been manipulated and represented by Disney and Kievnauchfilm, relatively speaking, I have found some interesting fundamental differences, namely; their relative treatment of the heroine, their relative treatment of the Queen, their relative treatment of the key theme of imagination and curiosity, and their relative atmosphere and mood. As I have established, both texts go out of their way to present the heroine of the story in their own particular light. While Disney disempowers and pacifies her, Kievnauchfilm does the exact opposite, turning her into an optimistic explorer and an icon of curiosity and imagination. While at a glance Disney’s treatment of Alice might seem peculiar and uncharacteristic of the ‘dream factory’ corporation, there is in fact an established trend of misogyny, sexism, and patriarchal stereotyping of women in Disney cartoons, and indeed American animation at large.86 For instance Snow White and Cinderella are both passive and traditional, they both “live in male dominated worlds. They are naturally happy homemakers (and they both)… play a subservient role.”87 Alice was simply the next in a line of heroines to be patronized, pacified and subordinated. This, compared to the bold and engaging heroine of Alisa in the Land of Miracles. While Soviet animation has a history of treating any primary literary sources of adaptation with 86 Clarke, J. Animated Films, p27-28 “Disney’s Full Length Animated Films” http://www.uleth.ca/edu/kid_culture/disney/essay.html, (3rd April 2008) 87 46 “the utmost respect”,88 Kievnauchfilm’s presentation of Alice goes somewhat beyond the book (as I have shown). Soviet animation also has a history of social criticism, selfreflection and optimism, which is precisely why it so empowers Alisa. As she journeys through wonderland, Alisa becomes the voice of reason, truth and optimism in her dealing with the Mad Hatter, the March Hare, and the Queen, thus she becomes an instrument of criticism and icon of hope and endurance. To explain my reasoning; as a film, Alisa is extremely purposeful and utilizes every scene and character to some effect, which leads me to believe that Alisa’s strength and perseverance in such a dark and surreal environment as wonderland is meant as a symbol of hope. This is significant with respect to Russia, which, in the early 1980s was a somber and troubling place as it became increasingly obvious to the public that their communist government was failing, turning corrupt, and abusing its power in a frightening and desperate manner. Furthermore, as aforementioned, the people were powerless and thus became despondent, turning away from politics, toward their televisions.89 Thus Kievnauchfilm presented them with a rebellious critique against what was happening and the resounding notion of hope and optimism to comfort and encourage them. Another issues arising from my comparative analysis, one completely related to the preceding two paragraphs, is the difference in Alice and Alisa’s depiction of the Queen and courtroom content found in Carroll’s original text. To continue with Alisa, Kievnauchfilm largely disempowers the Queen and her ‘pack of cards’, presenting her as an insecure, foolish and immature woman of no substance or character. This is in “Алиса в Стране Чудес, мультфильм, 1981” http://jabberwocky.ru/alisa-v-strane-chudesmulmztfilmzm-1981.html, (29th March 2008) 89 Lowe, N. Mastering Twentieth-Century Russian History, p387 88 47 accordance with the compelling theme of bureaucracy and misused power that is so central to Alisa. While Kievnauchfilm has largely followed the book and been faithful to Carroll’s depiction of events, the small discrepancies that do arise (which I have already outlined) are very suspect and suggestive. Furthermore the differences between Alice’s Queen and courtroom and Alisa’s are vast, as I will explain. The ‘bygone days’, the ‘attempts at resistance’, and the outrageous executioner dressed in red are all very indicative, suspect discrepancies from the book, and they all make perfect sense in relation to the Soviet Union with its disappearances, its bureaucracy and its “preoccupation with its own history”.90 These are all clear references to Soviet Russia, where Queen is the image of the state, the White Rabbit is perhaps the ‘voice behind the image’ and Alisa is the revolution against it. Hence by belittling the Queen, the court and the executioner, Alisa is empowering its viewers. This is all relatively straight-forward and clear, though things become more interesting when we look at Alice’s large, overbearing and extremely threatening Queen, more enraged than immature. The plot of the story has furthermore been hugely manipulated by Disney so that Alice is herself on trial, and in an extremely frightening and defeated position. While this could once again be explained by the evidence concerning Walt Disney’s political disposition and Alice’s role as a propaganda tool, it seems almost too unreal and extreme to be true. However, The evidence is overwhelming. To add to what I have already presented on this matter of Walt Disney’s political activism; during the war era Disney was commissioned to make propagandist films (thus establishing his experience in this field) and while doing so, Disney closely managed the production of 90 Gillespie, D. Russian Cinema, p60 48 Victory Through Air Power (1943) which “went beyond obligatory anti-Nazi satire to propagandise for strategic bombing”91 (thus establishing his personal interest and use it). The next interesting and (without considering the contexts in which these films were made) inexplicable difference between these two texts is their treatment of the key theme of Carroll’s text, imagination and curiosity. Disney resoundingly opposes and reverses this theme, while Kievnauchfilm vehemently promotes it. For Disney, a studio that is branded with the virtues of wonder, magic and innocence, it makes very little sense to turn a story about imagination and curiosity into a nightmarish cautionary tale, hence I am compelled to consider what reasoning might lie behind such an action. My only answer to this query is a political and social one: It is well known that Walt Disney was decidedly and very actively conservative, even testifying against his own employees “at the House (of) Un-American Activities Committee about suspected Communists”92 in 1947. Similarly it is well known that postwar America was a confused, curious and politically unstable place, particularly with the Cold War and McCarthyism (initiated under conservative government) terrifying and confusing the public. In such a time, Alice’s cautionary right wing disposition served as propaganda for the conservative party, warning that curiosity can be dangerous, and that ‘there is no place like home’. Although perhaps surprising, this analysis is supported by accounts from Disney’s production team, who accuse Walt of enforcing a certain “aesthetic conservatism” which had “political Ross, D. “Home by Tea-time: Fear of Imagination in Disney’s Alice in Wonderland” in Classics in Film and Fiction, p217 92 “Chronology of the Walt Disney Company” http://www.islandnet.com/~kpolsson/disnehis/disn1947.htm, (31st March 2008) 91 49 implications that were not lost on Disney’s staff.”93 At any rate this thematic decision certainly reflects the fearful, ‘buckled down’ mind frame of America in the 1950s. As for Alisa’s potent support of Carroll’s theme (and indeed, Alisa manipulates the text to reinforce this theme), I find Alisa to be a very unified and logical film in its reasons for being. What I mean by this is that Alisa has a goal, an intention, that informs most every aspect of it. That goal being; to provide social criticism on what was happening in the U.S.S.R. in the 1980s and furthermore provide the hope and motivation of overcoming these problems and the oppression and bureaucracy of the state. I say this after most every aspect of my textual analysis of the film seems to point in this direction. Thus, by campaigning for Carroll’s theme of imagination and fantastical dreaming, Alisa invited its viewers to be active, aware and curious about what was happening in the U.S.S.R., not to be defeated or disenfranchised, and most importantly, to keep dreaming, to be hopeful. There are other thematic issues to be found in both films, namely Alice’s integral theme of manners (expressed through Alice and her general conduct in wonderland) and Alisa’s theme of psychosis and clinical illness, that are seemingly very significant to America in the fifties and Russia in the eighties, though this is perhaps somewhat speculative. Alice plays up the theme of manners much more than Alisa does (and arguably more than the book as well) making it an exasperated constant issue of the text. This, I would argue, is a result of (or at least certainly a reflection of) the cultural and social circumstances of America in the 1950s, where (to reuse a quote) manners, presentation, “appearance and Ross, D. “Home by Tea-time: Fear of Imagination in Disney’s Alice in Wonderland” in Classics in Film and Fiction, p217 93 50 acceptance had replaced inner values as guidelines to life.”94 Meanwhile, Alisa dismisses the theme of manners and instead takes the silly, abstract and meaningless ‘Mad TeaParty’ chapter of Carroll’s book and turns it into a much more disturbing and realistic illustration of insanity and mental sickness. This intentional, disturbing, clinical presentation of the Mad Hatter and March Hare’s lunacy is a critique on the health crisis (or otherwise the general insanity of the governments management of the nation) that developed in the Soviet Union in this time. However neither of these points are wholly supportable, thus while they seem logical and functional, they are not acceptable or endorsed conclusions of this dissertation. Finally I would like to explore the atmosphere and general nature of Alice and Alisa as I believe the essences of these two films are cleanly relatable to their respective contexts of production. In essence, Alice is a floundering, confused and shallow film that does not seem to understand itself and its own overlooked darkness, while Alisa is a knowingly dark and mature film in many respects, though still retains a fantastical and optimistic outlook. Thus, both films have sinister and dark elements, though it is their reasoning for and use of this darkness that sets them so far apart. Alice, through aesthetic realism and manipulation of its characters and events, creates a very hostile and disturbing wonderland which serves the films chief goal of discouraging curiosity and child-like imagination and freedom. Otherwise put, Walt Disney’s “focus on realism forced (Alice’s production team) to abandon one of the most important functions of cartoons: to provide 94 Gordon, L. and Gordon, A. American Chronicle; Year by Year Through the Twentieth Century, p474 51 social criticism”95 and instead produce a conservative, cautionary, propagandist children’s animation… a combination which is deeply unsettling and morally reprehensible. This sinister and confusing ambiance likens Alice in a very fundamental way to the reality of 1950s America. It is increasingly apparent that in many respects Disney’s Alice is not so much an example of American animation in the fifties as it is a (albeit incidental) testament to the confusion and plastic appearance of American society and life in the fifties, and the fear that underlined it. In stark contrast to this, Alisa, through its use of socialist realism, presents wonderland as a dark and sinister realm only in order to liken it to the Soviet Union in the 1980s, thus communicating to its audience a (necessarily subtle) rebellious critique of the political regime of the U.S.S.R. This darkness, though very apparent, is subsequently evaluated and overcome by the film’s heroine, Alisa who symbolizes hope and perseverance. Thus Alisa is an example of how Soviet “film makers used a kind of Aesopian language, the language and allegory and parable, to say what could not be said.”96 Alisa ends in high spirits with the Queen (symbolizing the oppressive government) defeated and Alisa’s optimistic last words: “And I shall tell her outright, I don’t fear you therefore! I know I just sleep at night, and you’re my dream, nothing more!” (30:06). An encouraging end to the film that is surely meant to encourage, motivate and empower the masses. Ross, D. “Home by Tea-time: Fear of Imagination in Disney’s Alice in Wonderland” in Classics in Film and Fiction, p217 96 Smith, G.N. The Oxford History of World Cinema, p645 95 52 CONCLUSION The primary goal of this dissertation has been to explore the elaborate and comprehensive relationship that seemingly exists between film and society. The fact that film is a creative, expressive man made enterprise suggests that there should occur in most every film, through the intricacies of filmmaking, a very personal manifestation of the world as it appears to the creator of the film at the time of its creation. Like music and the fine arts it is inevitable that our own history and humanity would become tangled up in cinema as cause and effect, signified and signifier, reality and its reflection take turns in influencing one another in our minds, society, and the medium of film. This, of course, is a far too abstract and speculative issue to be the functioning basis for any academic work, thus my focus instead on the more manageable task of comparing two cinematic adaptations of a primary text and exploring their dissimilarities in relation to their respective contexts of production. This study has yielded some unexpected results, though it has not disappointed in the least, and has furthermore achieved precisely what it was intended to. My literature review of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland proved to be constructive to this dissertation in that it revealed a number of specific characteristics of the book that make it particularly well suited to the purpose of the expression and manifestation of social, political and other contextual circumstances. For instance, it is a text full of dark and sinister events that are otherwise concealed by its optimistic and inquisitive nature, it is a text that thematically addresses issues of lunacy, bureaucracy, 53 authority and curiosity, and it is a text that through nonsense lends itself to manipulation and expression of whatever one might wish to express. My contextual research reviewed and compared the America of 1951 to the Soviet Union of 1981 to reveal some interesting similarities and differences. To review these circumstances, economically America and Walt Disney were much stronger in their time than the Soviet Union and Kievnauchfilm were in theirs. Politically the situation was relatively comparable as oppression, suspicion and conservatism spread due to McCarthyism, the Cold War and the Brezhnev administration, which caused social upset in both cases, though the public of the U.S. and U.S.S.R. had a different way of dealing with this as America patriotically pretended everything was fine and Russia became stagnant, upset and eventually apathetic. The film and animation industry of America was growing and evolving, though struggling to attract audiences due to the mass onset of television, and Disney was monopolizing the world of animation, which was clearly defined as a genre for children. Meanwhile, it was in the eighties that the Soviet film industry began its decline with “talk of the death of national cinema.”97 The state was oppressive and interfered in media, though nonetheless the U.S.S.R. continued to produce some of the most socially reflective, artistic and imaginative animation in the world. My comparative textual analysis of Alice in Wonderland and Alisa in the Land of Miracles revealed some very expected, and some very unexpected differences between the two films. Many discrepancies that arose from my analysis were uncomplicated and were easily made sense of given the obvious differences between Russian and American 97 Faraday, G. Revolt of the Filmmakers, p1 54 society and animation, however other discrepancies arose which did not seem at all logical, and could not be understood in themselves, such as Disney’s cruel disempowering and pacifying of Alice, and furthermore overwhelming and distressing representation of wonderland and the Queen, or Kievnauchfilm’s peculiar alterations to the otherwise accurately portrayed text, the surreal, sinister imagery of the film, and its clinical depiction of insanity through the Mad Hatter and March Hare. In the final stage of this investigation I combined the contextual research of the first chapter with the analytical deductions of the second in order to explore whether the discrepancies that exist between Alice and Alisa could be understood or explained by the contexts in which the two films were made. Otherwise put, I considered my analytical findings with respect to my contextual findings, to see what knowledge might be gained from the amalgamation of the two. This final process provided answers to all the unsolved issues of my textual analysis and unearthed the reasons behind a fundamental difference between Alice and Alisa that differentiated most every aspect of them, from atmosphere to plot to themes to characters. Furthermore this final process identified an interesting array of factors that influenced the production of Alice and Alisa, from the trends of national art and cinema movements to the political affiliations and personal aesthetics of Walt Disney to the “spiritual and moral impasse”98 of Soviet life to the sexism and misogyny of post war America. In conclusion, this dissertation has effectively shown that Disney’s Alice in Wonderland and Kievnauchfilm’s Alisa in the Land of Miracles both reflect, in surprising detail, the 98 Gillespie, D. Russian Cinema, p115 55 contexts under which they were produced. Through specific textual manipulation of Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland both films effectively portray and reflect upon the political and social circumstances surrounding their creation, though Alice does so in a disturbing and propagandist manner while Alisa does so in a resoundingly hopeful and helpful one. Furthermore there is the fascinating, though wholly unintentional manner in which, due to Walt Disney’s conservative rule over the production of Alice, the film has poignantly captured the disjointed nature of life in America in the 1950s, where underneath the well mannered, patriotic and polished surface of society there lay a very sinister atmosphere that the few dared acknowledge. While Disney produced a film that is largely dictated by and hence representative of the environment in which it was made, Kievnauchfilm instead purposefully critiqued and symbolically defeated the oppressive social and political atmosphere surrounding its production. This understanding of Alice in Wonderland and Alisa in the Land of Miracles would not be plausible or justifiable without taking into account the grand, extensive contextual circumstances under which they were both produced. 56 BIBLIOGRAPHY PRIMARY SOURCES: Films: o Alice in Wonderland (1951) Directed by Geronimi, C. Jackson W. & Luske, H. [DVD] Walt Disney Productions o Alisa v Strane Chudes (1981) Directed by Pruzhansky, E. [DVD] Kievnauchfilm Books: o Carroll, L. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland Croydon: Penguin Books 2008 Web Resources: o “The Moscow Times” http://www.themoscowtimes.com, (20th January 2008) 57 SECONDARY SOURCES: Periodicals: o Kirk, D.F. “Charles Dodgson; Semeiotician” in University of Florida Monographs; Humanities no.11 (Fall 1962) Florida: University of Florida Press o Kotlarz, I. “The Birth of a Notion” in Screen 24/2 (March / April), p21-9. Books: o Allan, R. “Disney’s European Sources” in Girveau, B. Once Upon a Time: Walt Disney, The Sources of Inspiration for the Disney Studios London: Prestel 2007 o Barrier, M. Hollywood Cartoons; American Animation in its Golden Age New York: Oxford University Press 1999 o Bordwell, D. Thompson, K. Film History; An Introduction New York: McGrawHill Companies 2005 o Clarke, J. Animated Films London: Virgin Books 2004 o Clarke, S. & Smith, D. Disney; The First 100 Years New York: Disney Editions 1999 o Cousins, M. The Story of Film London: Pavilion 2004 o Crafton, D. Before Mickey; The Animated Film 1898-1928 Chicago: Chicago University Press 1993 58 o Dunlop, J.B. The Rise of Russia & the Fall of the Soviet Empire New Jersey: Princeton University Press 1993 o Eliot, M. Walt Disney, Hollywood’s Dark Prince New York: Birch Lane Press 1993 o Faraday, G. Revolt of the Filmmakers Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press 2000 o Gillespie, D. Russian Cinema London: Pearson Education 2003 o Gordon, L. and Gordon, A. American Chronicle; Year by Year Through the Twentieth Century New York: Vail-Ballow Press 1999 o Kinsey, A. Animated Film Making London: Studio Vista Limited 1970 o Lowe, N. Mastering Twentieth-Century Russian History New York: Palgrave Publishers Limited 2002 o Macfadyen, D. Yellow Crocodiles and Blue Oranges; Russian Animated Film Since World War Two Quebec: McGill-Queen’s University Press 2005 o McKee, A. Textual Analysis: A Beginner’s Guide London: Sage Publications 2003 o Ross, D. “Home by Tea-time: Fear of Imagination in Disney’s Alice in Wonderland” in Classics in Film and Fiction London: Pluto Press 2000 o Schickel, R. The Disney Version New York: Simon and Schuster 1968 o Schweizer, P. & Schweizer, R. The Mouse Betrayed; Greed, Corruption, and Children and Risk Wachington: Regnery Publishing 1998 o Smith, D. The Official Encyclopedia; Disney A to Z, 3rd ed. New York: Disney Enterprises 2006 59 o Smith, G.N. The Oxford History of World Cinema, New York: Oxford University Press 1996 o Smoodin, E. Animating Culture: Hollywood Cartoons from the Sound Era New Jersey: Rutgers University Press 1993 o Stephens, J. Language and Ideology in Children’s Fiction Essex: Longman Group 1992 o Taylor, R. Wood, N. Graffy, J. & Iordanova, D. Eastern European and Russian Cinema London: BFI 2000 o Williams, S. & Madan, F. The Lewis Carroll Handbook London: Oxford University Press 1962 Internet resources: o “Алиса в Стране Чудес, мультфильм, 1981” http://jabberwocky.ru/alisa-vstrane-chudes-mulmztfilmzm-1981.html, (29th March 2008) o “A good sledgehammer strike of a cartoon” http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0211191/, (23rd February 2008) o “About this Video” http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6zh3C-D9KpQ, (26th March 2008) o “Alice in Wonderland; By Lou Bunin” http://www.findinternettv.com/Video,item,552615244.aspx, (25th March 2008) 60 o “Alice in Wonderland; Film and TV productions across the years” http://www.alice-in-wonderland.fsnet.co.uk/film_tv_intro.htm, (20th February 2008) o “Alice in Wonderland Economics” http://www.valleypatriot.com/VP060507drchuck.html, (9th March 2008) o “Alice in Wonderland Syndrome” http://aiws.info/ (8th March 2008) o “Animation not reserved to Children” http://twitchfilm.net/archives/009301.html, (26th March 2008) o “Best Movies of 1981” http://www.mysubtitles.com/index.php?movies_from_year=1981&index=0, (17th March 2008) o “Chronology of the Walt Disney Company” http://www.islandnet.com/~kpolsson/disnehis/disn1947.htm, (31st March 2008) o “Commentary; The health crisis in the U.S.S.R., looking behind the façade” http://ije.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/35/6/1398, (22nd February 2008) o “Статья для ASIFA news” http://www.pilot-film.com/show_article.php?aid=16, (21st February 2008) translated by European Language Services (www.europeanonline.co.za) o “Disney’s Full Length Animated Films” http://www.uleth.ca/edu/kid_culture/disney/essay.html, (3rd April 2008) o “How to tell if you’re Ukrainian” http://www.zompist.com/ukraine.html, (22nd February 2008) 61 o “Kathryn Beaumont” http://www.alice-inwonderland.fsnet.co.uk/film_tv_disney2.htm, (20th February 2008) o “Kievnauchfilm (Kiev Science Film)” http://www.animator.ru/db/?ver=eng&p=show_studia&sid=94&sp=2, (21st February 2008) o “Lenny’s Alice in Wonderland Site” http://www.alice-inwonderland.net/explain/alice841.html, (2nd April 2008) o “Q & A Archives” http://imagiverse.org/questions/archives/disney1.htm, (24th March 2008) o “Timeline of Influential Milestones and Turning Points in Film History” http://www.filmsite.org/milestones1920s.html, (20th March 2008) o “Understanding Disney; The Manufacture of Fantasy” http://www.cjconline.ca/printarticle.php?id=890&layout=html, (23rd March 2008) o “Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination” http://www.powells.com/review/2006_12_26.html, (30th March 2008) 62