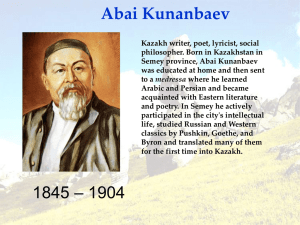

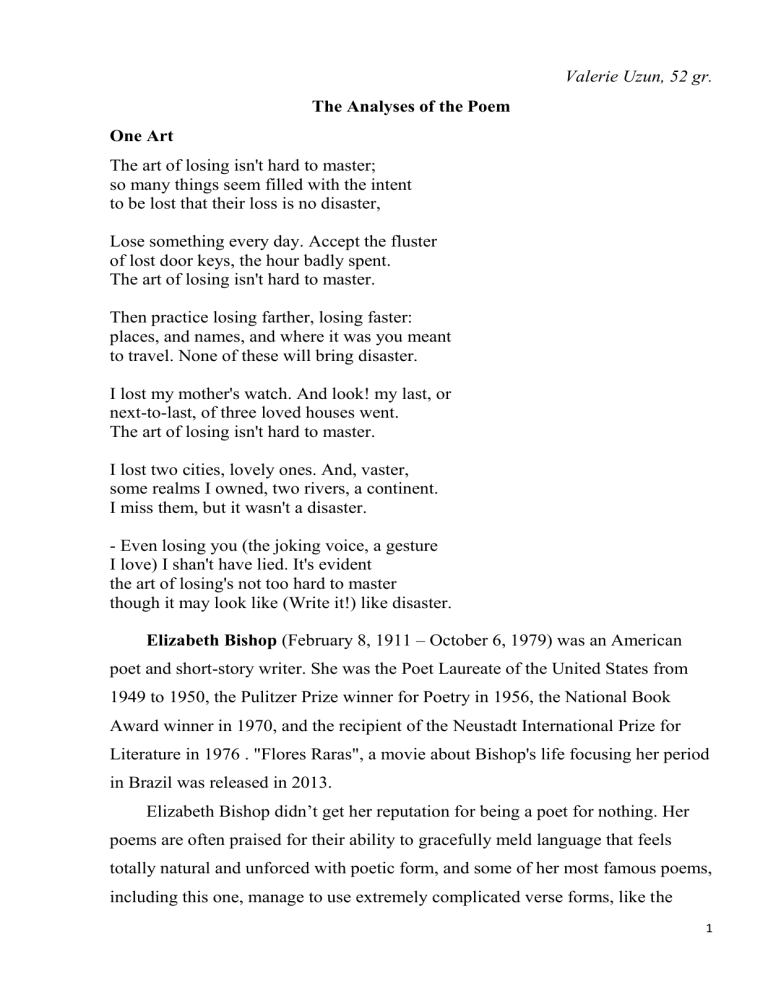

Valerie Uzun, 52 gr. The Analyses of the Poem One Art The art of losing isn't hard to master; so many things seem filled with the intent to be lost that their loss is no disaster, Lose something every day. Accept the fluster of lost door keys, the hour badly spent. The art of losing isn't hard to master. Then practice losing farther, losing faster: places, and names, and where it was you meant to travel. None of these will bring disaster. I lost my mother's watch. And look! my last, or next-to-last, of three loved houses went. The art of losing isn't hard to master. I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster, some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent. I miss them, but it wasn't a disaster. - Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture I love) I shan't have lied. It's evident the art of losing's not too hard to master though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster. Elizabeth Bishop (February 8, 1911 – October 6, 1979) was an American poet and short-story writer. She was the Poet Laureate of the United States from 1949 to 1950, the Pulitzer Prize winner for Poetry in 1956, the National Book Award winner in 1970, and the recipient of the Neustadt International Prize for Literature in 1976 . "Flores Raras", a movie about Bishop's life focusing her period in Brazil was released in 2013. Elizabeth Bishop didn’t get her reputation for being a poet for nothing. Her poems are often praised for their ability to gracefully meld language that feels totally natural and unforced with poetic form, and some of her most famous poems, including this one, manage to use extremely complicated verse forms, like the 1 villanelle and the sestina, while maintaining a sense of real-time conversation and clarity. Bishop’s work is also notable for its tone of calm reflection and sometimes unexpected bursts of humor. The title "One Art" works on two levels; on the first, we can take the meaning of the title from the first line, and assume that the "art of losing" (1.1) is the only art here. However, if we take a closer look at the poem, we see that the art of writing is also in the mix here – and that these two experiences, losing something and crafting a poem, are inextricably interwoven. The "one art" of the title combines loss, coping with loss, and expressing the experience through verse. "One Art" approaches loss in a rather sidelong manner; it doesn’t dive straight in and attack the big issues, like the loss of a home or a loved one, but instead begins with the little things that we lose here and there. In so doing, Bishop aligns these unimportant possessions with the more significant things we "own." As the poem goes on, the objects mentioned become more and more meaningful, as does their loss. We see by the end that the loss of simple objects, like a key or a watch, becomes an extended metaphor for the loss of other things the poet loves, such as her past homes or lovers. Lines 2-3: The poet personifies the lost objects, stating that they "seem filled with the intent/ to be lost" (1.2-3); that is to say, they want to get lost. Lines 4-5: "Lost door keys" (2.4) are mentioned alongside misspent hours, and we see that objects and more abstract things, like time, are viewed equivalently here. Line 10: The poet mentions casually that she lost her mother’s watch – but there’s more going on here than meets the eye. She’s already getting into the territory of emotionally significant objects, and we can be sure that the watch is a symbol for her relationship with her mother. The poet’s brief discussion of homes and places that she’s loved provides a smooth segue into the final stanza, in which she reveals that the poem is actually about the loss of a loved one. The idea of possession and loseable things is greatly expanded by her inclusion of "three loved houses" (4.11), and in the following 2 stanza, "two cities" (5.13) and "some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent" (5.14). Lines 10-11: The ante is upped by the introduction of a new idea: the loss of a home. The poet mentions that she lost "[her] last, or/ next-to-last, of three loved houses" (4.10-11). Lines 13-14: The poet takes this abstraction one step further, mentioning not only specific homes, but also beloved cities and a continent that she’s lost. This makes us wonder exactly how she "owned" (5.14) these places; these mentions of place are perhaps symbolic of the memories she had of them, or of the relationships she once had there. Art is a double-edged sword here. The poet focuses on "the art of losing," which she depicts as something wherein practice makes perfect. However, this isn’t necessarily an art we can ever truly master. The poem’s ironic command that we "lose something every day" (2.4) to practice getting over the sensation of loss implies that if we lose enough small things, we’ll be ready when we lose bigger or more important ones. No matter how practiced we become at the art of losing, though, we can never really be prepared for losses, which will always seem like "a disaster." The other art involved in this poem is that of poetry. The entire poem functions as a kind of coping mechanism for the poet, who forces herself to confront her losses by writing them down. Line 1 (repeated in lines 6, 12): This refrain serves as the backbone of the poem. Its meaning gradually shifts as the poem goes on; rather than being totally straightforward, it grows more and more ironic as we see that "the art of losing" is indeed quite hard to master. Line 18: In this final appearance of the refrain we see it somewhat modified: the poet admits that "the art of losing’s not too hard to master," a significant change from the more confident tone of the original. Line 19: The poet’s internal command ("Write it!") alerts us to a couple of things: first of all, this is a very self-aware nod to the fact that the poet is 3 writing a poem; secondly, it shows us that she has difficulty admitting the pain of her loss, even to herself. Villanelle The villanelle is a complicated verse form, to say the least. It’s actually quite famous for its convoluted structure, and the resulting difficulties it can present to writers. The villanelle has nineteen lines, divided up into six stanzas. The first five have three lines and last stanza has four. The form follows a very specific rhyme scheme. The poem utilizes two rhymes – that is to say, everything either rhymes with [a] or [b] (in Bishop’s poem, all the lines rhyme with either "master" or "intent"). To further complicate things, there are two refrains, which are lines that are repeated several times. Here, Bishop sticks consistently to one refrain, "the art of losing isn’t hard to master," which she only slightly modifies at the end: "the art of losing’s not too hard to master." Theoretically, the villanelle should have a second line like this, that’s repeated throughout the poem. Bishop, however, takes some liberties here, and instead of actually repeating lines verbatim, her second so-called refrain always ends in the word "disaster" (lines 3, 9, 15, and 19). Conclusion The speaker in "One Art" isn’t new to the troubles of life and love; she’s been around the block a few times, and probably feels like she’s seen it all. We know that the speaker well traveled and has lived in her share of different places, and we can imagine that she’s probably loved her share of people, too. Her experience has taught her that no matter how terrible a loss seems, people always survive, and the lesson she attempts to teach her readers (and herself) in this poem echoes that idea. The phrase "The art of losing isn’t hard to master" (1.1), urges us to get used to the idea of loss, and to accept that some things just can’t stay. Underneath this placidly resigned surface, however, we get the feeling that this speaker still feels each loss profoundly. 4