1 Альтернативная спецификация издержек освоения капитала

реклама

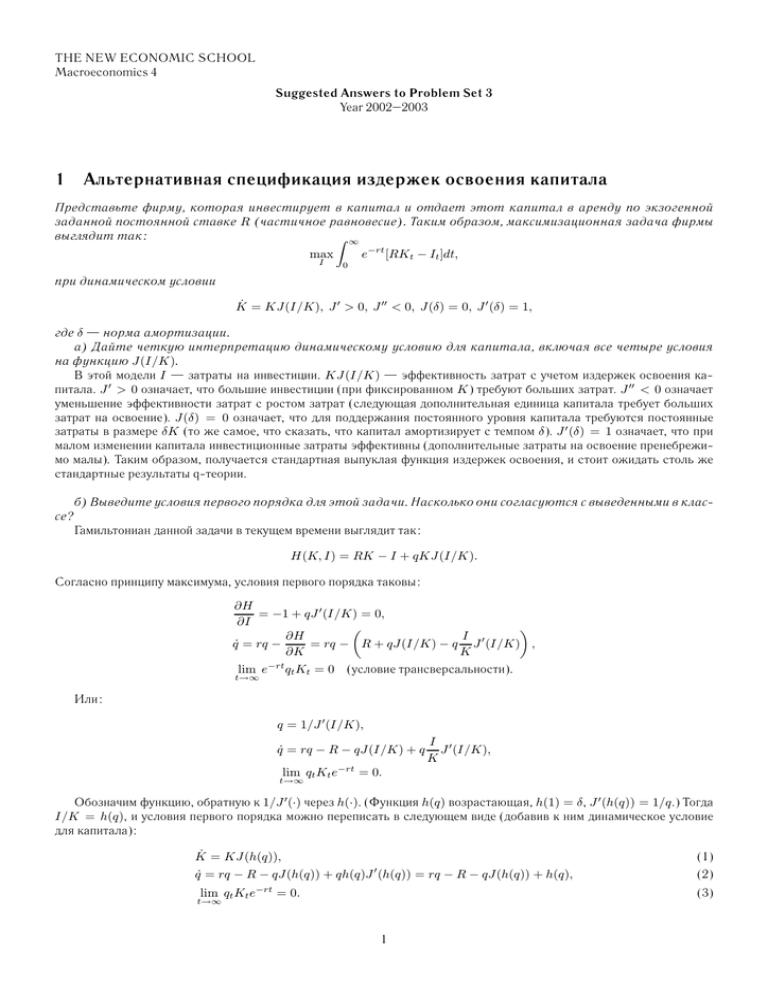

THE NEW ECONOMIC SCHOOL Macroeconomics 4 Suggested Answers to Problem Set 3 Year 2002–2003 1 Альтернативная спецификация издержек освоения капитала Представьте фирму, которая инвестирует в капитал и отдает этот капитал в аренду по экзогенной заданной постоянной ставке R (частичное равновесие). Таким образом, максимизационная задача фирмы выглядит так: ∞ e−rt [RKt − It ]dt, max I 0 при динамическом условии K̇ = KJ(I/K), J > 0, J < 0, J(δ) = 0, J (δ) = 1, где δ — норма амортизации. а) Дайте четкую интерпретацию динамическому условию для капитала, включая все четыре условия на функцию J(I/K). В этой модели I — затраты на инвестиции. KJ(I/K) — эффективность затрат с учетом издержек освоения капитала. J > 0 означает, что большие инвестиции (при фиксированном K) требуют больших затрат. J < 0 означает уменьшение эффективности затрат с ростом затрат (следующая дополнительная единица капитала требует больших затрат на освоение). J(δ) = 0 означает, что для поддержания постоянного уровня капитала требуются постоянные затраты в размере δK (то же самое, что сказать, что капитал амортизирует с темпом δ). J (δ) = 1 означает, что при малом изменении капитала инвестиционные затраты эффективны (дополнительные затраты на освоение пренебрежимо малы). Таким образом, получается стандартная выпуклая функция издержек освоения, и стоит ожидать столь же стандартные результаты q-теории. б) Выведите условия первого порядка для этой задачи. Насколько они согласуются с выведенными в классе? Гамильтониан данной задачи в текущем времени выглядит так: H(K, I) = RK − I + qKJ(I/K). Согласно принципу максимума, условия первого порядка таковы: ∂H = −1 + qJ (I/K) = 0, ∂I I ∂H = rq − R + qJ(I/K) − q J (I/K) , q̇ = rq − ∂K K lim e−rt qt Kt = 0 (условие трансверсальности). t→∞ Или: q = 1/J (I/K), q̇ = rq − R − qJ(I/K) + q lim qt Kt e−rt = 0. I J (I/K), K t→∞ Обозначим функцию, обратную к 1/J (·) через h(·). (Функция h(q) возрастающая, h(1) = δ, J (h(q)) = 1/q.) Тогда I/K = h(q), и условия первого порядка можно переписать в следующем виде (добавив к ним динамическое условие для капитала): K̇ = KJ(h(q)), q̇ = rq − R − qJ(h(q)) + qh(q)J (h(q)) = rq − R − qJ(h(q)) + h(q), lim qt Kt e−rt = 0. (1) (2) (3) t→∞ 1 Полученные условия почти не отличаются от выведенных в классе. Единственное существенное отличие заключается в том, что в уравнении (2) отсутствует K. Это является следствием линейности «производственной функции» RK по K. Если же сделать замену переменной V /K = J(I/K) (V — инвестиции), то затраты на инвестирование запишутся в виде I = V (J −1 (V /K)/(V /K)). В классе затраты записывались в виде I = V (1 + φ(V /K)), где функция xφ(x) была выпукла и имела минимум в нуле. В нашей модели xφ(x) = J −1 (x) − x. Нетрудно проверить, что она выпукла и достигает минимума в нуле. Если положить δ = 0, то затраты на инвестиции станут в точности такими, как на лекции. в) Существует ли стационарный режим в данной модели, где стационарный режим определяется как K̇ = q̇ = 0 ? Если да, то при каких условиях, и является ли он единственным? Рассмотрим уравнение (1). Условие K̇ = 0 эквивалентно (считаем, что K не может быть равным нулю) условию J(h(q)) = 0, или h(q) = δ, или q = 1. Подставим условие q = 1 в уравнение (2). Получим, что 0 = r − R − J(h(1)) + h(1)J (h(1)) = r − R + δ. Таким образом, если R = r + δ, то стационарного состояния в модели не существует. Если R = r + δ, то весь луч q = 1 состоит из стационарных состояний (заметим, что для них условие трансверсальности выполнено). г) Изобразите получившуюся систему на фазовом портрете в пространстве q, K, с капиталом, отложенным по горизонтальной оси, для случая, когда стационарный режим существует. Так как функция J(h(q)) возрастающая (суперпозиция двух возрастающих), то K̇ > 0 при q > 1, K̇ < 0 при q < 1. Аналогичное условие для q̇, вообще говоря, неверно, но в окрестности прямой q = 1 функция rq−R−qJ(h(q))+h(q) являетчя возрастающей по q. Действительно, (rq − R − qJ(h(q)) + h(q)) = r − J(h(q)) − qJ (h(q))h (q) + h (q) = r − J(h(q)). В точке q = 1 это выражение равно r. Значит, в окрестности прямой q = 1 q̇ > 0 при q > 1, q̇ < 0 при q < 1. Таким образом, траектории динамической системы имеют следующий вид (на рисунке изображена только одна из них): q 1 . . q=K=0 . K Решения задачи максимизации — стационарные состояния (переходной динамики в данной модели нет). 2 Investment and the Housing Market Consider the following model of the housing market (due to Jim Poterba) : I = ψ(P ), ψ > 0 R + Ṗ P R = R(H). R < 0 r+δ = Ḣ = I − δH where I is gross investment in housing, P is the price of a house, R is the rental cost of a house, and r is the real interest rate. (a) Explain why each of the equations of the model is reasonable. 2 The first equation is the supply of gross investment, which is an increasing function of the price of a house. Builders will undertake more investment in the housing stock (build more houses), the higher is the price of a house. This is the supply curve for the flow of new housing and is upward sloping in the price. Notice that the stock of housing H is fixed at any point in time and is thus price-inelastic. The second equation is the arbitrage equation for the owner of the house. Bringing δ, the depreciation rate, to the RHS, we get the exact expression for the return on renting the house to some one else (dividend in terms of rental rate, capital gains/losses and the depreciation). In order to eliminate the opportunity of arbitrage profits, this rate should equal the interest rate. We can integrate this equation to show that P is the present value of future expected rental income, with the appropriate discount rate (r + δ). The third equation is the inverse demand curve for houses. The fourth equation is the accumulation equation for houses: net investment into housing equals gross investment less depreciation. (b) Write the model in terms of two variables (a state variable and costate variable) and two equations of motion. To answer this problem, we first recognize that the state variable in this setting is H. After all, we are given the accumulation equation for the variable, which suggests that the stock of houses cannot jump, but rather adjusts slowly. It is worth noting, however, that we have not imposed any adjustment costs to housing, and hence there is no economic reasons why this variable should not be allowed to jump. Nonetheless, the shadow price of H should be the costate variable. In fact, we are given the price of housing, P , in our equations. The other two endogenous variables are I and R, and we can easily eliminate them via simple substitution. Thus, the equations of motion are Ḣ = I − δH = ψ(P ) − δH, Ṗ = (r + δ)P − R = (r + δ)P − R(H). (c) In a phase diagram, display the system’s dynamics To find the Ḣ = 0 locus, notice that Ḣ = 0 implies ψ(H) = δH. Totally differentiating, we can find the slope of this line in (H, P ) space : δ dP > 0. = dH Ḣ=0 ψ (P ) Thus, the Ḣ = 0 locus is upward-sloping. Next, Ṗ = 0 implies that (r + δ)P = R(H). Totally differentiating, dP R (H) <0 = dH Ṗ =0 r+δ so that Ṗ = 0 locus is downward sloping. The graph below shows these two lines with the intersection being the steady state. P . H=0 E P* . P=0 H* H The graph also shows the arrows of motion. Here is how we find them. Consider points above the Ḣ = 0 locus. For a given level of H, a P which is above the level consistent with zero net investment implies that investors must be adding to the housing stock (ψ(P ) > 0). That is, Ḣ > 0 in that region, and hence, the opposite is true on the opposite side of the isocline. Mathematically, just look at the accumulation equation for H and see that an increase in P holding H constant increases growth rate of H. Now consider the Ṗ = 0 locus. Accumulation equation shows that an increase in P makes Ṗ increase, and hence arrows should point up above the locus and down below it. Intuitively, high price means that returns to housing are low (look back at the second equation of the model). To compensate house-owners for that, capital gains must be high. 3 (d) What is the steady state effect on H, P, I, and R of an increase in the real interest rate r? First, it should be apparent that Ḣ = 0 locus is not affected by this shock. But locus Ṗ = 0 shifts to the left, as is demonstrated on the graph below : P . H=0 P* P** . P=0 . P=0|r H* H** H Does a higher r leading to smaller amount amount of housing and lower price make sense intuitively ? At the steady state (i.e. in absence of capital gains or losses) an increase in r must be matched by an increase in R(H) − δ in order to satisfy the P arbitrage equation and make investors indifferent. The RHS will increase if P or H fall. If the return on other assets rises, investors shift towards those assets, until the returns are equal again. If the stock of houses falls, then the gross investment I should also fall at steady state, since there is less depreciation to take care of. (e) What is the effect on h, P, I, and R over time of an unanticipated, permanent increase in the rental rate r? At the time of shock, the price must jump to the new stable arm and converge to the new steady state : P . H=0 P* P** . P=0 H* H** H Why does P overshoot its steady state value ? Since H cannot jump, at the point of the shock there are more houses than investors wish to have. In order for the arbitrage condition to hold, the price of the houses should be rising. But the new steady state value is below the old. Hence, the price has to jump yet further down initially to give itself some room for growth. Paths of all variables demonstrated below : r P, I H R t1 t 4 The corresponding time paths are : r P, I H R t2 t1 t (f) What is the effect of an unanticipated, temporary increase in real interest rate? Suppose the shock hits at time T1 and lasts till T2 . At T2 , we need to arrive precisely at the old stable arm following a dynamic path in the interim. Hence, we have to jump immediately to that dynamic path which will take us to the old stable arm, when it returns: P . H=0 P* P** . P=0 H* H** H (g) What is the effect of a pre-announced future permanent increase in the real interest rate? Suppose the announcement is made at T0 . Again, we need to do the jumping at this point, because an anticipated jump in price creates profit opportunities and should be ruled out. Until time T1 of the shock, we need to be on a dynamic path that will take us to the new stable arm precisely at T1 , as is demonstrated on the graph: P . H=0 P* P** . P=0 H* H** and the time paths are : 5 H r P, I H R t2 t1 t Suppose that instead of having rational expectations (here, perfect foresight) about the price of a house, people have static expectations - they expect that the price of a house will never change from what it is now. Redo part (e) under this new assumption In this case, we get from the second equation of the model that all of the adjustment will have to be done through the rental rate, which will increase together with r. P will stay the same, and therefore, gross investment will not change either. 3 Asymmetric Information and Market Collapse Consider the following model of student loans (following Gregory N. Mankiw). Each student decides whether to take a bank loan and invest in education, which will bring an expected return R to the student, but with probability P the student will default and pay nothing to the bank. R, P are heterogeneous across students; students know their own values, but the bank only knows the general distributions. Specifically, the average probability of default is Π. The bank can invest into a risk-free security with return ρ or lend to student at interest rate r. The banks and students are risk-neutral. (a) Equalizing returns for banks, what is the relation between r and ρ given that the banking sector is competitive? Call this condition (1). Доход банка от вложения в безрисковый актив равен ρ. Средний доход банка от кредита студенту равен (1 − Π)r (процент, умноженный на вероятность возврата кредита). Если банковский сектор конкурентен, то должно быть выполнено условие (1 − Π)r = ρ. (1) Иначе, если (1 − Π)r > ρ, то банк-конкурент понизит ставку r и переманит всех клиентов. Если (1 − Π)r < ρ, то рынка займов не будет, так как банки предпочтут вложить средства в безрисковый актив. (b) For the student, what is the expected return and expected payment for loan? Under what condition will the student take a loan? Draw this condition in P , R space. Will all students for whom R > ρ take the loan? What about the other? Why or why not? Ожидаемый выигрыш студента равен R, ожидаемая плата за кредит равна (1−P )r. Значит, студент возьмет кредит, если R > (1 − P )r. На рисунке показана область в пространстве P , R, где студенты берут кредит. P . 1 A D ρ r R 6 Заметим, что студенты, чьи P , R лежат в области D не берут кредит, несмотря на то, что R > ρ. Это потому, что собственная оценка вероятности дефолта у студента ниже, чем у банка, исходящего из средней вероятности. С другой стороны, студенты из области A берут кредит, несмотря на то, что их доход R мал. Вероятность невозврата кредита у них велика, поэтому ожидаемый выигрыш положителен. (c) For the bank, what is the probability of repayment conditional on the knowledge about what type of students take the loan (use the answer to (b) in answering this question) ? Write down the corresponding function Π(r), and call it condition (2). Средняя вероятность невозврата кредита теми студентами, кто его взял под процент r, равна Π(r) = E[P | R > (1 − P )r]. (2) Замемтим, что чем выше r, тем меньше студентов с высокой вероятностью возврата кредита будет брать кредит. Значит, условное матожидание Π(r) возрастает по r. (d) Draw conditions (1) and (2) in the Π, r space. Will there always be an equilibrium? На рисунках ниже показаны два случая: в первом из них равновесие существует. во втором — нет. Π . 1 (1) (2) ρ Π r2 r1 r . 1 (1) (2) ρ r (e) Solve for a particular case when R is constant and P is uniform. Under what conditions will there be an equilibrium? Если R постоянно и P распределено равномерно на [0, 1] (для простоты ограничимся только этим случаем), то при R r все студенты возьмут кредит, и 1−Π(r) = 1−E[P | R > (1−P )r] = 1/2. Если R < r, то условное распределение вероятности вернуть кредит равномерное на отрезке [0, R/r], следовательно, 1−Π(r) = 1−E[P | R > (1−P )r] = R/2r. Добавив к этому условию условие 1 − Π = ρ/r, получаем, что при R < 2ρ равновесия нет. При R > 2ρ равновесное значение r определяется из условия ρ/r = 1/2 или r = 2ρ. При R = 2ρ решений бесконечно много, но имеет смысл брать только крайнее левое из них, т. е. r = 2ρ. (f) What does this model imply about the sensitivity of investment with respect to the interest rate? Can this model help understand the collapse of investment during the Great Depression in the U.S. and in Russia of 1990s? В данной модели инвестиции крайне чувствительны к процентной ставке ρ. Действительно, возможна ситуация, когда малое изменение ρ приведет к обрушению рынка инвестиций (ситуация, когда ρ перескакивает отметку R/2). Рост поцентной ставки может произойти, например, в результате ограничительной денежной политики центробанка. Так что отчасти эта модель позволяет понять причины коллапса рынка инвестиций. Кроме этого, небольшое увеличение рисков само по себе может привести к полному коллапсу системы. Bernanke (1983) утверждает, что такой механизм ускорил развитие Великой депрессии, так как банки перестали в силу рискованности давать кредиты. Такая же ситуация часто называется причиной отсутствия кредитования в российской экономике. 7