CAMBRIDGE

UNIVERSITY

PRES S

Cambridge,

New York,Melbourne,Madrid, CapeTown,Singapore,

Sio Paulo,Delhi

CambridgeUniversityPress

The EdinburghBuilding,CambridgeCB2 8RU,UK

www.cambridge.org

Information on this title: www.cambridge.org19780521,449946

@ CambridgeUniversity

Press1991

It is normallynecessary

for writtenpermissionfor copyingto be

obtainedin aduancefrom a publisher.The worksheets,role play

card,testsandtapescripts

at the backof this book aredesigned

to

be copiedand distributedin class.The normal requirements

are

waivedhereand it is not necessaryto write to CambridgeUniversity

Pressfor permissionfor an individual teacherto make copiesfor use

within his or her own classroom.Only thosepageswhich carry the

wording 'O CambridgeUniversityPress'may be copied.

Firstpublished1996

lTth printing2009

Printedin the United Kingdomat rhe UniversiryPress,Cambridge

A cataloguerecordfor this publicationis auailablefrom the British Library

Library of CongressCataloguingin Publicationdata

Ur, Penny.

A coursein languageteaching:practiceand theory / PennyUr.

p. cm.

Includesbibliographical

refrrences.

ISBN978-0-521

-44994-6paperback

1. Languageand language- Studyand teaching.I. Title

P51.U71995

41.8'.007- dc20

94-35027

CIP

ISBN 978-0-521-44994-6

Paperback

CambridgeUniversityPresshas no responsibilityfor the persistence

or

accuracyof URLs for externalor third-party Internetwebsitesreferredto in

this publication,and doesnot guaranteethat any contenton suchwebsitesis,

or will remain,accurateor appropriate.Information regardingprices,travel

timetablesand other factual information givenin this work are correctat

the time of first printing but CambridgeUoiversityPressdoesnot guaranree

the accuracyof suchinformation thereafter.

Gontents

Units with a ) symbol are componentsof the 'core' course;thosewith a F

symbolare'optional'.

Acknowledgements

ix

Readthisfirst To the (trainee)teacher

To thetrainer

xii

xl

lntroduction

Module

1:Presentations

andexplanations

) Unit One: Effectivepresentation

D Unit Two: Examplesof presentationprocedures

) Unit Three: Explanationsand instructions

LI

1.3

L6

2:Practice

Module

activities

) Unit One: The function of practice

) Unit Two: Characteristicsof a good practiceactiviry

) Unit Three: Practicetechniques

D Unit Four: Sequenceand progressionin practice

19

21,

24

27

Module

3:Tests

'What

are testsfor?

) Unit One:

Unit

Two:

Basic

concepts;

the test experience

)

Unit

Three:

Typ"r

elicitation

of

test

techniques

)

Four:

Designing

Unit

a

test

F

F Unit Five: Testadministration

11

JJ

35

37

41,

42

4:Teaching

Pronunciation

Module

'What

doeste4chingpronunciation involve?

) Unit One:

F Unit Two: Listeningto accents

) Unit Three: Improving learners'pronunciation

F Unit Four: Further topics for discussion

) Unit Five: Pronunciationand spelling

,

47

50

52

54

56

Contents

Mo d u 5

l e:T e a ch ivo

n gca bular y

) Unit One: \fhat is vocabulary and what needsto be taught?

) Unit Two: Presentingnew vocabulary

tr Unit Three: Rememberingvocabulary

) Unit Four: Ideasfor vocabularywork in the classroom

F Unit Five: Testingvocabulary

60

63

64

68

69

Mo d u 6

l e:T e a ch ignra

g mm ar

'Vfhat

is grammar?

) Unit One:

F Unit Two: The place of grammar teaching

tr Unit Three: Grammaticalterms

) Unit Four: Presentingand explaining grammar

) Unit Five: Grammar practiceactivities

Grammaticalmistakes

D Unit Six:

75

76

78

81

83

85

Module

7:Topics,

situations,

notions,

functions

) Unit One: Topics and situations

) Unit Two: What ARE notions and functions?

) Unit Three: Teachingchunks of language:from rext to task

F Unit Four: Teachingchunks of language:from task to text

F Unit Five: Combining different kinds of languagesegments

90

92

93

96

98

Module

8:Teaching

listening

) Unit One: \7hat doesreal-life listeninginvolve?

) Unit Two: Real-lifelisteningin the classroom

tr Unit Three: Learnerproblems

) Unit Four: Typesof activities

F Unit Five: Adapting activities

105

1,07

1.1,1,

1,1,2

115

Mo d u 9

l e:T e a ch isp

n ge a king

) Unit One: Successfuloral fluencypracice

) Unit Two: The functions of topic and task

) Unit Three: Discussionactivities

F Unit Four: Other kinds of spokeninteracrion

F Unit Five: Role play and relatedtechniques

Oral testing

D Unit Six:

120

1.22

1,24

1,29

131.

133

Mo d u l1e0T: e a ch ire

n ga ding

) Unit One: How do we read?

F Unit Two: Beginningreading

) Unit Three: Typesof readingactivities

) Unit Four: Improving readingskills

F Unit Five: Advancedreading

VI

138

1,41

143

147

150

Contents

Module

11:Teaching

writing

F Unit One: Written versus spoken text

) Unit Two: Teachingprocedures

) Unit Three: Tasks that stimulate writing

D Unit Four: The processof composition

) Unit Five: Giving feedback on writing

t59

r62

r64

1.67

170

M o d u l1e2 :T hsyl

e labus

'Sfhat

is a syllabus?

) Unit One:

) Unit Two: Different fypes of language syllabus

) Unit Three: Using the syllabus

176

777

179

M o d u l1e3 :Ma te ri a l s

) Unit One: How necessaryis a coursebook?

) Unit Two: Coursebookassessment

) Unit Three: Using a coursebook

F Unit Four: Supplementarymaterials

worksheetsand workcards

F Unit Five: Teacher-made

183

1,84

1,87

1,89

192

Module

14:Topic

content

) Unit One: Different kinds of content

) Unit Two: Underlying messages

tr Unit Three: Literature (1): should it be included in the course?

) Unit Four: Literature (2): teachingideas

D Unit Five: Literature (3): teachinga specifictext

197

199

200

202

206

M o d u l1e5L: e ssopnl a n n i n g

) Unit One: What doesa lessoninvolve?

D Unit Two: Lessonpreparation

) Unit Three: Varying lessoncomponents

F Unit Four: Evaluatinglessoneffectiveness

) Unit Five: Practicallessonmanagement

2t3

2t5

216

2L9

222

16:Classroom

interaction

Module

) Unit One: Patternsof classroominteraction

) Unit TWo: Questioning

) Unit Three: Group work

) Unit Four: Individualization

D Unit Five: The selection of appropriate activation techniques

227

229

232

233

237

M o d u l1e7Gi

: vi nfe

g e d b a ck

)Unit One:

Different approachesto the nature and function of

feedback

242

vll

Contents

D Unit Two: Assessment

) Unit Three: Correctingmistakesin oral work

) Unit Four: lTritten feedback

D Unit Five: Clarifying personalattitudes

244

246

250

253

: l a ssrodoim

Mo d u l1e8C

scipline

) Unit One: What is discipline?

) Unit Two: What doesa disciplinedclassroomlook like?

D Unit Three: What teacheraction is conduciveto a disciplined

classroom?

) Unit Four: Dealing with disciplineproblems

F Unit Five: Discipline problems:episodes

2s9

260

262

264

267

motivation

Module

19:Learner

andinterest

D Unit One: Motivation: somebackgroundthinking

F Unit Two: The teacher'sresponsibility

) Unit Three: Extrinsic motivation

) Unit Four: Intrinsic motivation and interest

F Unit Five: Fluctuationsin learnerinterest

274

276

277

280

282

Module

20:Younger

andolder

learners

'What

differencedoesagemake to languagelearning?

) Unit One:

D Unit Two: Teachingchildren

D Unit Three: Teachingadolescents:studentpreferences

D Unit Four: Teachingadults: a different relationship

286

288

290

294

Module

21:Large

heterogeneous

classes

) Unit One: Defining terms

) Unit Two: Problemsand advantages

) Unit Three: Teachingstrategies(L): compulsory + optional

) Unit Four: Teachingstrategies(2): open-ending

D Unit Five: Designingyour own activities

302

303

307

309

3L2

Module

22:Andbeyond

vlll

F Unit One: Teacherdevelopment:practice,reflection,sharing

F Unit Two: Teacherappraisal

tr Unit Three: Advancing further (1): intake

F Unit Four: Advancing further (2): output

318

322

324

327

Bibliography

360

In d e x

367

Acknowledgements

I should like to thank all those who have contributed in different ways to this

book:

- To editor Marion'STilliams, who criticised, suggestedand generally

supported me throughout the writing process;

- To Cambridge University Press editors Elizabeth Serocold and Alison Sharpe,

who kept in touch and often contributed helpful criticism;

- To Catherine Walter, who read the typescript at a late stage and made

practical and very useful suggestions for change;

- To my teachers at Oranim, with whom I have over the years developed the

teacher-training methodology on which this book is based;

- And last but not least to my students, the teacher-trainees, in past and present

pre-service and in-service courses, to whom much of this material must be

familiar. To you, above anyone else, this book is dedicated; with the heartfelt

wish that you may find the fulfilment and excitement in teaching that I have;

that you may succeed in your chosen careers, and may continue teaching and

learning all your lives.

The authors and publishersare grateful to the authors,publishersand otherswho have

given their permission for the use of copyright information identified in the text. \7hile

everyendeavourhas beenmade,it has not beenpossibleto identify the sourcesof all

material usedand in suchcasesthe publisherswould welcomeinformation from

copyright sources.

p6 diagram from ExperentialLearning: Experienceas the Sourceof Learning and

Deuelopmenrby David Kolb, published by PrenticeHall, 1984@ David Kolb; p14 from

'Exploiting textbook dialoguesdynamically' by Zokan Drirnyei, PracticalEnglisb

Teacbing,1986,614:1.5-16,and from 'Excuses,excuses'by Alison Coulavin, Practical

English Teaching,1983,412:31@ Mary Glasgow MagazinesLtd, London; p14 from

English Teacher'sJournal, 1986,33; p48 from Pronunciation Tasksby Martin

Hewings, Cambridge University Press,1993;p77 (extracts1 and 2) from 'How nor to

interferewith languagelearning' by L. Newmark and (extract3) from 'Directions in the

teachingof discourse'by H. G. Widdowson in The CommunicatiueApproach to

LanguageLearning bV C.J. Brumfit and K. Johnson (eds.),Oxford University Press,

1979,by permissionof Oxford Univer3ityPress;p77 (extract4) from Awarenessof

Language:An Introdwction by Eric Hawkins, Cambridge University Press,1984;p116

adapted from TeachingListening Comprehensionby PennyUr, Cambridge University

Press,1984;p130 (extract 1) from The LanguageTeachingMatrix by Jack C. Richards,

Cambridge University Press,1990;p1.30(extract2) from Teachingtbe SpokenLanguage

by Gillian Brown and GeorgeYule, Cambridge University Press,1983;p130 (extract3)

from Discussionsthat Work-by PennyUr, Cambridge University Press,1981;pp 130-1

from Ro/e Play by G. Porter-Ladousse,Oxford University Press,1987,by permissionof

Oxford Univsrsity Press,pl51 from Task Reading by EvelyneDavies,Norman

Whitney, Meredith Pike-Blakeyand Laurie Bass,CarnbridgeUniversity Press,1.990,p152

from Points of Departure by Amos Paran,Eric Cohen Books, 1.993;p153 from Effectiue

Reading: Skillsfor AduancedStudentsby Simon Greenall and Michael Swan, Cambridge

IX

Acknowledgements

University Press,1985; Beat the Burglar, Metropolitan Police; p157 (set 3) from A few

short hops to Paradise'by JamesHenderson, The Independenton Sunday,l'1'.12'94,by

permission of The Independent; p160 from Teaching.Written English by Ronald V

'White,Heinemann Educational Books, 1980,by permissionof R. .White;p207'Teevee'

from Catch a little Rhyme by Eve Merriam @ 1966 Eve Merriam. @ renewed 1994 Dee

Michel and Guy Michel. Reprinted by permission of Marian Reiner; p251 from English

Grammar in[Jseby Raymond Murphy, Cambridge University Press,1985;p269 (episode

1 and 3) from ClassManagementand Controlby E. C. Wragg,Macmillan, 1981,

(episode2 and 5) adapted from researchby Sarah Reinhorn-Lurie;p281 (episode4) and

p291 from Classroom Teacbing Skillsby E. C. Wragg, Croom Helm, L984; p323 based

on Classroom Obseruation Tasks by Ruth !(ajnryb, Cambridge University Press,t992.

Drawings by Tony Dover. Artwork by Peter Ducker.

Rea

dthisfirst

This book is a coursein foreign languageteaching,addressedmainly to the

trainee or novice teacher,but some of its material may also be found interesting

by experiencedpractitioners.

If it is your coursebookin a trainer-ledprogramme of study then your trainer

will tell you how to use it. If, however, you are using it on your own for

independent study, I suggestyou glance through the following guidelines before

starting to read.

How to use the book

1. Skim through, get to know the'shape'of the book

Beforestarting any systematicstudy,have a look at the topics as laid out in the

Contents,leaf through the book looking at headings,read one or two of the

tasksor boxes.

The chaptersare called'modules' becauseeachcan be usedindependently;

you do not have to have done an earlier one in order to approach alatet On the

whole, however,they are ordered systematically,with the more basictopics

first.

2. Do not try to read it all!

This book is rather long, treating many topics fairly fully and densely.It is not

intendedto be read cover-to-cover.Someof the units in eachmodule are 'core'

units, marked with a black arrowhead in the margin next to the heading;you

should find that thesegive you adequatebasiccoverageof the topic, and you

can skip the rest. However,glanceat the 'optional' units, and if you find

anything that interestsyou, use it.

3. Using the tasks

The tasks are headedTask, Question,lnquiry, etc., and are printed in bold.

They often refer you to material provided within a rectangular frame labelled

Boxz for example in Module 1, Unit One there is a task in which you are asked

to considera seriesof classroomscenariosin Box 1.1, and discusshow the

teacherpresentsnew material in each.

The objectiveof the tasks is to help you understandthe material and study it

thoughtfully and critically - but they are rather time-consuming.Those that are

clearly meant to be done by a group of teachersworking togetherare obviously

impractical if you are working alone, but othersyou may find quite feasibleand

rewarding to do on your own. Someyou may prefer simply to read through

xl

Readthis first

without trying themyourself.In any case,possiblesolutionsor comments

usuallyfollow immediatelyafter the task itself, or areprovidedin the Notes

sectionat the endof eachmodule.

If vou areinterestedin moredetailedrntormatronabout the materialin this

book and the theory behindit, go on to reaclthe lntroductron on Pages1-9.

To the trainer

This book presentsa systematicprogrammeof studyintendedprimarily for preserviceor noviceteachersof foreignlanguages.

Structure

whichI havecalled'modules',sincetheyare

It is composedof.22chapters

Eachmoduleis dividedinto unitsof study;a unit

intendedto befree-standing.

usuallytakesbetweenoneandtwo hoursto do.

A foundationcourseis providedby the coreunits (labelledwith black

arrowheadsin the marginwheretheyoccurin the book,and in the Contents);

sucha coursewould takeabout50-80 hoursof classtime if you do not

it in anyway.Someof the optionalunitsmay be substitutedfor core

supplement

units whereyou feelit appropriatefor your own context,or simply addedfor

further enrichment.An evenshortercoufsemay be basedon the coreunits of

onlv the first elevenmodules.

courses;a Isingle

for short

snort rn-servrce

rn-servrce

modulesmay

mavbeusedas basestor

Individual

lndrvrdualmodules

module,studiedin its entireryshouldtakeaboutonestudyday (aboutsix

tl

nours,to get tnrougn.

Content

The materialin the modulesincludesinformation, tasksand study basedon

practiceteachingand observation.

The information sectionscan furnish eithera basisfor your own input

checkson

sessions

or readingfor trainees.Thereareoftenbrieftasks(questions,

which may be usedfor shon

within thesesections,

interspersed

understanding)

or homewriting assignments.

discussions

to materiallaid out in the boxes:for

Tasksareusuallybasedon responses

examplea box may displaya shortscenarioof classroominteraction,and the

readeraskedto criticizethe way the teacheris elicitingstudentresponses.

'Where

appropriate,possiblesolutionsor my own ideason the issuesaregiven

immediatelybelowthe task.This closejuxtapositionof questionsand answers

is intendedto savethe readerfrom leafingback and forth looking for the

is that traineesmay be temptedto look

but the disadvantage

answerselsewhere,

first. The

on to the answerswithout engagingproperlywith the task themselves

of fne

the

probablyto maKe

makecopresor

problemls proDably

practicalsolutron

this problem

s olutionto thls

most practlcal

relevantbox (which should be marked@CambridgeUniversityPress)and hand

instructionsyourself,so that trainees

them out separatelygiving any necessary

xll

Readthis first

do not needto open the book at all in order to do the task; they may later be

referredto the possiblesolutionsin the book for comparisonor further

discussion.

How much you usethe tasksinvolving teachingpracticeand observation

depends,of course,on whether your traineesare actually teachingor have easy

and the viewing of

accessto activelanguage-learningclasses.Peer-teaching

video recordingsof lessons(for example,Looking at LanguageClassrooms

(t996) CambridgeUniversity Press)may be substitutedif necessary.

The Trainer'snotesat the end of the book add somesuggestionsfor

variations on the presentationof the different units, and occasionallycomment

on the background,objectivesand possibleresultsof certain tasks.They also

include estimatesof the timing of the units, basedon my experiencewhen doing

them with my own traineeslhowever,this is, of course,only a very rough

approximation, and variesa greatdeal, mainly dependingon the needfelt by

you and the traineesto developor cut down on discussions.

The following Introduction providesmore detailson the content and layout

of the book and its underlying theory and educationalapproach.

xlll

lntroduction

Gontent

The main part of this book is divided into 22 modules,eachdevotedto an

aspectof languageteaching(for example'grammar', or 'the syllabus').At the

end of most modulesis a set of Notes, giving further information or comments

on the tasks.Also attachedto eachmodule is a sectionentitled Further reading,

which is a selectedand annotatedbibliography of books and articlesrelevantto

the topic.

The modulesare grouped into sevenparts, eachfocussingon a cerftralaspect

or themeof foreign languageteaching:Part I, for example,is calledThe

teacbingprocess)and its modulesdeal with the topics of presentation,practice

and testing.Eachpart has a short introduction definingits theme and clarifying

the underlying concepts.

Each module is composedof severalseparateunits: theseagain are freestanding,and may be usedindependentlyof one another.Their content

includes:

l.lnput: background information, both practical and theoretical.Suchinput is

intendedto be treatednot as somekind of objective'truth' to be accepted

and learnedas it stands,but as a summary of ideasthat professionals,

scholarsand researchershave produced and which teachersthereforemay

benefitfrom studying and discussing.Thesesectionsmay simply be read by

teachersindependentlgor mediatedby trainers through lecturesessions.

Input sectionsare usually precededor followed by questionsor tasksthat

allow readersto reflecton and interact with the ideas,checkunderstanding

or discusscritically; in a trainer-ledsessionthey can serveas the basisfor

brief group discussionsor written assignments.The point of this is to ensure

that traineesprocessthe input and make their own senseof it rather than

simply acceptinga body of transmittedinformation.

2. Experiential work: tasks basedon teaching/learningexperience,which may

be one or more of the following:

a) Lessonobservation:focussingon the point under study.

b)Classroom teaching:where the teachertries out different procedureswith

classesof foreign languagelearners.

c) Micro-teaching:the teacherteachessmall groups of learnersor an

individual learnerfor a short period in order to focus on a particular

teachingpoint.

d) Peer-teaching:

one of a group of teacherstries out a procedureby

'teaching'the rest of the group.

lntroduction

e) Experiment: teacherstry out a techniqueor processof learning or

teaching,document resultsand draw conclusions.

f) Inquiry: a limited aspectof classroomteachingis studied through

observation,practice, or limited survey;the resultsof the study may be

written up and made availableto others.

Most experientialwork is followed by critical reflection,usually in the

form of discussionand/or writing. Its aim is to allow teachersto processnew

ideasthoughtfully and to form or test theories.

For teacherswho are not in a position to try out experientialprocedures

themselves,somepossibleresultsand conclusionsare given within the unit

itself or in the Notes at the end of the module.

3. Tasks:learning tasks done by teachersin groups or individually, with or

without a trainer, through discussionor writing. Thesemay involve such

processesas critical analysisof teachingmaterials,comparison of different

techniques,problem-solvingor free debateon controversialissues;their aim

is to provoke careful thinking about the issuesand the formulation of

personaltheories.Brief tasks may be labelled Question, Application or To

checkunderstanding,and usually follow or precedeinformational sections.

As with the experientialtasks,suggestedsolutions,resultsor commentsare

suppliedwhere appropriate: immediately following the task if they are seenas

useful input in themselves;or in the Notes at the end of the module if they are

seenrather as optional, perhapsinteresting,additions (my own personal

experiences,for example,or further illustration).

Different componentsare often combined within a unit: a task may be basedon

a reading text, or on teachingexperience;an idea resulting from input may be

tried out in class.This integration of different learning modesprovides an

expressionin practice of the theory of professionallearning on which this book

is based,and which is discussedin the Rationale below.

Note that although this courseis meant for teachersof any foreign language,

examplesof texts and tasks are given throughout in English (exceptwhen

another languageis neededfor contrast). The main reasonfor this is that the

book itself is in English, and I felt it was important as a courtesyto the reader to

ensurethat all illustrative material be readily comprehensible.Also, of course,

English itself is probably the most widely taught languagein the world today;

but if you are concernedwith the teachingof another language,you may need

to translateor otherwiseadapt texts and tasks.

The collection of topics on which the modules are basedis necessarily

selective:it is basedon those that furnish the basisfor my own (pre-service)

teacher-trainingprogramme, and which seemto me the most important and

useful.The last module of the book includesrecommendationsfor further

studS with suggestedreading.

lntroduction

Rationale

Defining concepts

'Training' and'education'

The terms 'teachertraining' and 'teachereducation' are often usedapparently

interchangeablyin the literature to refer to the samething: the professional

preparation of teachers.Many prefer 'teachereducation', since'training' can

imply unthinking habit formation and an over-emphasison skills and

techniques,while the professionalteacherneedsto developtheories,awareness

of options, and decision-makingabilities- a processwhich seemsbetter defined

by the word 'education' (see,for example,Richardsand Nunan,l'9901. Others

have made a different distinction: that 'education' is a processof learning that

developsmoral, cultural, social and intellectualaspectsof the whole personas

an individual and member of society,whereas'training' (though it may entail

some'educational'components)has a specificgoal: it preparesfor a particular

function or profession(Peters,1,9662Ch.I). Thus we normally refer to 'an

educatedperson', but'a trained scientist/engineer/nurse'.

The secondof the two distinctionsdescribedabove seemsto me the more

useful:this book thereforeusesthe term 'training'throughout to describethe

processof preparation for professionalteaching,including all aspectsof teacher

development,and reserves'education' for the more varied and generallearning

that leadsto the developmentof all aspectsof the individual as a memberof

society.

Practice and theory

Teacherscommonly complain about their training: 'My coursewas too

theoretical,it didn't help me learn to teach at all'; or praisea trainer: 'Sheis so

practical!' Or they say: 'It's fine in theory, but doesn'twork in practice.'It

soundsas if they are sayingthat theory is uselessand practiceis what they

want. And indeedthis is what many teachersfeel.But they are understanding

the two words in a very specificway: 'theory' as abstract generalizationthat has

no obvious connection with teaching reality; 'practice' as tips about classroom

procedure. The two conceptsare understood rather differently in this book.

Practiceis definedhere as (a descriptionof) a real-time localizedevent or set

of such events:particular professionalexperiences.Theory is a hypothesisor

classes

conceptthat generalizes;it may cover a set of practices('heterogeneous

learn better from open-endedtasksthan from closed-endedones');or it can

describephenomenain generalterms ('languageis usedfor communication'); or

it can expressa personalbelief ('languagelearning is of intrinsic value'). (For a

more detaileddiscussionof different types of theory seeStern, 1'983:23-32.)

Experiencing or hearing about practice is of limited use to the teacher if it is not

made more widely applicableby being incorporatedinto somesort of

theoretical framework constructed and 'owned' by the individual. For example,

you might learn about a brainstorming activity ('How many things can you

think of that ... ?') which can be usedat certain levelsfor practisingcertain

language;but if that is all you learn, then you will only ever be able to useit in

the particular context where you learnt it. However, if you then think out why

lntroduction

the activityis useful,or defineits basicfeaturesand purposesin generalterms,

or relateit to the kind of learningit produces- in otherwords,construct

theoriesto explainit - you are enabledto criticizeand designotherideasand

will know when and why to usethem. Good theoriesgeneratepractice;hence

Kurt Lewin'sfamousdictum:'Thereis nothingsopracticalasa goodtheory.'A

teacherwho hasformed a clearconceptionof the principlesunderlyinga

particularteachingprocedurecanthenusethoseprinciplesto inform and create

furtherpractice;otherwisethe originalprocedurernayremainmerelyan

isolated,inerttechniquewhich canonly be usedin onespecificcontext.In other

words,practiceon its own, paradoxicallgis not verypractical:it is a deadend.

Theory on its own is evenmore useless.

A statementlike 'Languageis

communication',

for example,is meaningfulonly if we canenvisage

its

implementation

in practice.If you reallybelievein the theoreticalconceptcalled

'communicative

languageteaching',andhavemadeit your own, this will

expressitselfin the kindsof practicalcommunicative

you use.If you

techniques

in fact usemostlymechanical

drills in class,your practiceis inconsistent

with

the theory,andclearlyyou do not genuinelybelievein the latter:you havenot

madeit your own, but havemerelgin Argyrisand Schon's(L974)terms,

'espoused'

it. 'Espoused'

theoriesthat areclaimedby an individualto betrue

but haveno clearexpression

in practice- or areevencontradictedby it - arethe

foundationof the kind of meaningless

theorythat traineescomplainabout.

Predictivehypotheses

producedby researchers

or theoristsaresimilarly

dependent

on classroompracticefor their validationand usefulness.

For

example,accordingto audiolingualism,peoplewill learnlanguages

best

throughmimicryandrepetition.Doesthis accordwith your own classroom

experience?

If not, thenthe theoryasit standsis useless

to you; but if you can

processit andreformulateit for yourselfassomethingthat is true in the light of

('Mimicry and repetitionhelpstudentsX to learnY under

your own experience

conditionsZ') thenit becomes

meaningfuland helpful.

This book attemptsto maintaina consistentlink betweenpracticeand theory:

theoreticalideasaretestedthroughand illustratedby practicalexamples,

while

samplesof practicearediscussed

and analysedin orderto studytheir wider

theoreticalimplications.

The integrationof practiceandtheorywithin the processof professional

learningis described

in moredetailin the section'Enrichedreflection'below

Foreignlanguageteaching

Finallg two briefcommentson the term 'foreignlanguageteaching',asit is

understoodin this book.

Learningmay takeplacewithout conscious

teaching;but teaching,asI

understand

it, is intendedto resultin personallearningfor students,and is

worthlessif it doesnot do so.In otherwords,the conceptof teachingis

understoodhereasa processthat is intrinsicallyandinseparably

boundup with

learning.Youwill find, therefore,no separate

of languagelearningin

discussion

this book;instead,both contentand processof the variousmodulesconsistently

requirethe readerto studylearners'problems,needsand strategies

asa

necessary

basisfor the formulation of effectiveteachingpracticeand theory.

Second,it is necessary

to distinguishbetween'teaching'and 'methodology'.

Foreignlanguageteachingmethodologycanbe definedas'the activities,tasks

4

lntroduction

and learning experiencesused by the teacherwithin the [language]teachingand

learningprocess'(Richards,1.990:351.Any particular methodologyusually has

a theoreticalunderpinningthat should causecoherenceand consistencyin the

choiceof teachingprocedures.'Foreign languageteaching',on the other hand,

though it naturally includesmethodologg has further important components

such as lessonplanning, classroomdiscipline,the provision of interest- topics

which are relevantand important to teachersof all subjects.Suchtopics,

therefore,are included in this book as well as the more conventional

methodology-basedonessuchas'teaching reading'.

Models of teacher learning

Various modelsof teacherlearning have beensuggested;the three main ones,as

describedin \Tallace(1,993),are as follows:

1. The craft model

The traineelearnsfrom the exampleof a 'masterteacher',whom he/she

observesand imitates.Professionalaction is seenas a craft, rather like

shoemaking or carpentry, to be learned most effectively through an

apprenticeshipsystemand accumulatedexperience.This is a traditional

method, still usedas a substitutefor postgraduateteachingcoursesin some

countries.

2. The applied sciencemodel

The trainee studiestheoreticalcoursesin applied linguisticsand other allied

subjects,which are then, through the construction of an appropriate

methodology,applied to classroompractice.Many university-and collegebasedteacher-trainingcoursesare based,explicitly or implicitly on this idea of

teacherlearning.

3. The reflective model

The traineeteachesor observeslessons,or recallspast experience;then reflects,

alone or in discussionwith others,in order to work out theoriesabout teaching;

then tries theseout again in practice.Sucha cycleaims for continuous

improvementand the developmentof personaltheoriesof action (Schon,1'983).

This model is usedby teacherdevelopmentgroups and in somerecently

designedtraining courses.

Vhich is likely to be most effective?Or, perhapsa better question:how do

teacherslearn most effectively,and how can this learning be integrated into a

formal courseof study?

I have severaltimes askedgroups of teachersin different countriesfrom

what, or whom, they feel they learnedtheir presentteachingexpertiseand

knowledge.Various possiblesourceswere suggested,such as colleaguesand

'masterteachers',the literature, pre- or in-servicecourses,their own experience

as teachers,their students,their own experienceas learnersland teacherswere

askedto rate eachof thesein importancefor professionallearning.Every time

the majority replied that personalteachingexperiencewas by far the most

important. (Try this yourself with teachersyou know!)

lntroduction

This answermakessenseon an intuitive, personallevel as well. I myself have

done my bestto read, study,discusswith colleagues,attend coursesand

conferencesin order to improve my professionalknowledge.Nevertheless,if

asked,I would make the samereply as the teachersin my survey:I have learnt

most through (thinking about) my own teachingexperience.This doesnot mean

that other sourcesof knowledge and learning processesdo not contribute; but it

doesmean that they are probably lessimportant.

Thus, I have chosento basethis courseprimarily on the 'reflectivemodel' as

defined at the beginning of this section.

My only reservationis that this model can tend to over-emphasizeexperience.

Coursesbasedon it have sometimesusedthe (student-)teachersthemselvesas

almost the sole sourceof knowledge,with a relative neglectof external input lectures,reading,and so on - which help to make senseof the experiencesand

can make a very real contribution to understanding.As I seeit, the function of

teacherreflectionis to ensurethe processingof any input, regardlessof where it

comes from, by the individual teacher,so that the knowledge becomes

personally significant to him or her. Thus a fully effective reflective model

should make room for external as well as personalinput.

Perhapswe might call this model 'enrichedreflection'! It is describedbelow.

'Enrichedreflection'

Kolbt (1984) theory of experientiallearning elaboratesthe idea of 'experience+

reflection'. He definesfour modes of learning: concrete experience,reflective

observation,abstractconceptualizationand activeexperimentation.In order for

optimal learningto take place,the knowledgeacquiredin any one mode needs

to be followed by further processingin the next; and so on, in a recursivecycle.

Thus, concreteexperience('somethinghappenedto me in the classroom'),which

involvesintuitive or'gut' feeling,should be followed by reflectiveobservation

('let me step back and look at what took place'),which involveswatching and

perception;this in its turn is followed by abstractconceptualization('what

principle, or concept,can I formulate which will accountfor this event?'),

involving intellectualthought; then comesactiveexperimentation('let me try to

implementthis idea in practice'),involving real-time action which will entail

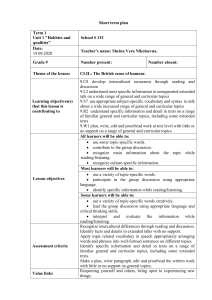

further concreteexperience... and so on (seeBox 0.1).

BOX0.1:EXPERIENTIAL

LEARNING

Concrete

con ceptua Ii zation

(basedon D. A. Kolb, Experiential

Learning:Experienceas the

S ourceof Learni ngand

Development,PrenticeHall,

1984, p. 42t-

lntroduction

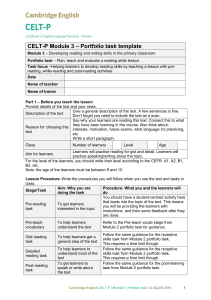

This model, however, needsto be enriched by external sourcesof input. It is

unrealisticand a wasteof time to expecttraineesto 'reinvent the wheel': this is

like expecting physics students to discover known laws of physics through their

own experimints. There is a lot to be learnt from experiencedteachers(asin the

craft model), from experts,from researchand.from reading (asin the applied

sciencemodel) - provided all this can be integratedinto one'sown reflectionbasedtheories.So at eachstageof Kolb's circle let us add the external sources:

experiencecan be vicarious (i.e. second-hand,such as observation,anecdote,

video, transcripts);descriptionsof other people'sobservationscan add to our

ownl theoreticalconceptscan come from foreign languageresearchersand

thinkers; ideasfor or descriptionsof experimentsfrom writers or other

professionals.And the initial stimulusfor a learning cycleof this kind can occur,

of course,at any of the eight points, not just at the point of experience(seeBox

0.2\.

REFLECTION'

BOX0.2:'ENRICHED

Vicarious

conceptualization

t\ Inputfrom professional

research,theorizing

Thus, sourcesof knowledgemay be either personalexperienceand thought

or input from outside;but in either casethis knowledgeshould, in principle, be

integiated into the trainees' own reflective cycle in order that effective learning

may take place.

To summarize:the,mostimportant basisfor learningis personalprofessional

practice;knowledgeis most usefulwhen it either derivesdirectly from such

practice,or, while deriving originally from other sources,is testedand validated

ihrough it. Hence the subtitle of this book: Practice and Theory, rather than the

more conventionalTheory and Practice.

The role of the trainer

Sucha model of professionallearning has, of course,implications for the role of

the trainer. In the 'craft model', the trainer is the masterteacher,providing an

exampleto be followed. The'applied science'modelalso givesthe trainer an

authoritative role, as the sourceof theory which the teacheris to interpret in

lntroduction

practice.Theconventional'reflecdvemodel',in contrast,caststhe trainerin the

role of 'facilitator'or'developer',givinglittle or no information,but

encouraging

traineesto developtheir own bodyof knowledge.

Accordingto the modelsuggested

here,the functionof the traineris neither

just to 'tell' the traineeswhat theyshouldbe doing,nor - just asbad- ro refuse

to tell themanythingin orderfor themto developall their knowledgeon rheir

own. The functionsof the trainer,I believe,are:

- to encourage

traineesto articulatewhat theyknow andput forward new

ideasof their own;

- to provideinput him- or herselfandto makeavailablefurthersourcesof

relevantinformation;

- and,aboveall, to gettraineesto acquirethe habit of processing

input from

eithersourcethroughusingtheir own experience

andcriticalfaculty,so that

theyeventuallyfeelpersonal'ownership'of the resultingknowledge.

Whatthe traineeshouldget from the course

Teachers,

asmentionedabove,generallyagreethat theylearnedmostfrom their

own experience

andreflectionwhile in professional

practice.Someevenclaim

that theylearnedeverythingfrom experience

andnothingfrom theirpre-service

courseat all- this is especially

true of thosewho took coursesthat were

predominantlytheoretical.

Pre-service

courses,

howevergood,cannotnormallyproducefully competent

practitionerswho canimmediatelyvie with their experienced

colleagues

in

expertise.

This is probablytrue of trainingcoursesin all theprofessions.

On the

otherhand,without an effectivecourseincomingteachers

will merely

perpetuate

the way theyweretaughtor rheway colleagues

reach,with little

opportunityto encounternew ideas,to benefitfrom progressmadein the field

by otherprofessionals,

researchers

andthinkers,or to developpersonaltheories

of actionthroughsystematic

studyandexperiment.The primaiy aim,then,of

sucha courseis to bringtraineesto the point at whichthiy can beginto

functioncompetentlyandthoughtfullgasa basisfor furtherdevelopment

and

improvementin the courseof their own professional

practice.occasionally

coursegraduates

arealreadywell on theirway to excellence,

but mostof us

start(ed)our teachingcareersat a fairlymodestlevelof competence.

Thus,a second,importantaim of the courseis to lay the seedsof further

development.

The courseshouldbe seenasthe beginningof a process,

not a

completeprocessin itself:participantsshouldbeencouraged

to develophabits

of learningthat will carrythroughinto laterpracticeandcontinuefor iheir

entireprofessional

lives(SeeModule22: And beyondl.

Finally,thereis a morelong-termaim: to promotea view of teachers

as

autonomousandcreativeprofessionals,

with responsibility

for the wider

development

of professional

theoryandpractice.This is in clearoppositionto

the 'appliedscience'modelof teacherlearning,which carrieswithli the

implicationthat thereis a hierarchyof prestigeand authority.In sucha

hierarchythe research

experrsand academics

takethehighestplace,and the

classroom

teachers

thelowest(Schon,1,983;

Bolitho,1988).Thejob of the

classroomteachers

is merelyto interpretand implementtheorywhichis handed

down to themfrom the universities.

They(theteachers)

areallowedto take

8

lntroduction

decisions,but only thosewhich affect their own classroompractice.In contrast,

this book supportsa view that teacherscan and should developtheoriesand

practicesthat are useful both within and beyondthe limits of their own

writings in Rudduck and Hopkins, 1985); and that

classrooms(seeStenhouse's

such a messageshould be conveyedthrough pre- and in-servicetraining.

Coursesshould lead traineesto rely on their own judgementand to be confident

enoughto discussand criticize ideasput forward by others,whether local

They should also

colleagues,trainers,lecturers,or universityresearchers.

promote individual researchand innovation, in both practical and theoretical

topics, and encouragethe writing up and publication of original ideasfor

sharingwith other professionals.

References

Argyris, C. and Schon,D. A. (1,974)Theory in Practice:IncreasingProfessional

Effectiueness,SanFrancisco:JosseyBass.

Bolitho, R. (1988) 'Teaching,teachertraining and applied linguistics',TDe

TeacherTrainer,2, 3, 4-7.

Kolb, D. A. (1934) Experiential Learning: Experienceas tbe Sowrceof Learning

and Deuelopment,Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey:PrenticeHall.

Peters,R. S. (1966) Ethics and Education,London: GeorgeAllen and Unwin.

Richards,J. (,990) The LanguageTeachingMatrix, Cambridge:Cambridge

UniversiryPress.

Richards,J. and Nunan, D. (1990) SecondLangwageTeacherEducation,

Cambridge:CambridgeUniversity Press.

Rudduck, J. and Hopkins, D. (1985) Researchas a Basisfor Tehching:

Readingsfrom the uork of LawrenceStenhouse,London:Heinemann

EducationalBooks.

Schon,D. A. (1983) The ReflectiuePractitioner:How ProfessionalsThink in

Action, New York: BasicBooks.

Stern,H. H. (1983) FundamentalConceptsof LangwageTeaching,Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Wallace, M. (1993) Training Foreign Language Teachers:A Reflectiue

Approach, Cambridge:CambridgeUniversity Press.

process

The processof teaching a foreign languageis a complex one: as with many

other subjects,it has necessarilyto be broken down into components for

purposesof study. Part I presentsthree such components:the teaching acts of

( 1) presentingand explaining new materi aI; (2) providing practice; and (3)

testing. Note that the first two conceptsare understood here rather differently

from the way they are usually usedwithin the conventional'presentationpractice-production' paradigm.

In principle, the teaching processesof presenting,practising and testing

correspond to strategiesused by many good learnerstrying to acquire a foreign

languageon their own. They make sure they perceiveand understand new

language(by paying attention, by constructing meanings,bI formulating rules

or hypothesesthat account for it, and so on); they make consciousefforts to

learn it thoroughly (by mental rehearsalof items, for example, or by finding

opportunities to practise);and they check themselves(get feedbackon

performance, ask to be corrected). (For a thorough discussionof rhe cognitive

processes

and strategiesof languagelearners,seeO'Malley and Chamot, 1990.1

In the classroom,it is the teacher'sjob to promote thesethree learning

processesby the useof appropriateteachingacts.Thus, he or she:presentsand

explainsnew material in order to make it clear,comprehensibleand available

for learning; givespractice to consolidateknowledge; and tests,in order to

checkwhat has beenmasteredand what still needsto be learnedor reviewed.

Theseactsmay not occur in this order,and may sometimesbe combinedwithin

one activity; neverthelessgood teachersare usually aware which is their main

objective at any point in a lesson.

This is not, of course,the only way peoplelearn a languagein the classroom.

They may absorb new material unconsciouslSor semi-consciously,

through

exposure to comprehensibleand personally meaningful speechor writing, and

through their own engagementwith it, without any purposeful teacher

mediation as proposed here. Through such mediation, however,the teachercan

provide a framework for organized,consciouslearning, while simultaneously

being aware of - and providing opportunities for - further, more intuitive

acqulsltron.

Thus, the three topics of presentation,practice and testing are presentedin

the following units not as the exclusivesourceof studentlearning,nor as

representinga rigid linear classroomroutine, but rather as simplified but

comprehensivecategoriesthat enableusefulstudy of basicteachingacts.

Reference

O'MalleS J. M. and Chamot, A. U. (1990) Learning Strategiesin Second

LanguageAcquisition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

10

Module

1:Presentations

andexplanations

Unit One: Effective presentation

The necessityfor presentation

It would seemfairly obvious that in order for our students to learn something

new (a texq a new word, how to perform a task) they needto be first able

to perceiveand understandit. One of the teacher'sjobs is to mediatesuch new

material so that it appearsin a form that is most accessiblefor initial

learning.

This kind of mediation may be called 'presentation';the terrn is applied here

not only to the kind of limited and controlled modelling of a target item that we

do when we introduce a new word or grammatical structure, but also to the

initial encounter with comprehensibleinput in the form of spoken or written

texts, as well as various kinds of explanations,instructionsand discussionof

new languageitems or tasks.

Peoplemay, it is true, perceiveand even acquire new languagewithout

'We

consciouspresentation on the part of a teacher.

learn our first language

mostly like this, and there are somewho would argue for teaching a foreign

languagein the sameway - by exposinglearnersto the languagephenomena

without instructional intervention and letting them absorb it intuitively.

However, raw, unmediated new input is often incomprehensibleto learners; it

doesnot function as 'intake', and thereforedoesnot result in learning.In an

immersion situation this doesnot matter: learnershave plenty of time for

repeatedand different exposuresto such input and will eventuallyabsorb it. But

given the limited time and resourcesof conventionalforeign languagecourses,

as much as possibleof this input has to becomealso 'intake' at first encounter.

Hencethe necessityfor presentingit in such a way that it can be perceivedand

understood.

Another contribution of effective teacher presentationsof new material in

formal coursesis that they can help to activateand harnesslearners'attention,

effort, intelligenceand conscious('metacognitive')learning strategiesin order

to enhancelearning- again, somethingthat doesnot necessarilyhappenin an

immersion situation. For instance,you might point out how a new item is

linked to something they aheady know, or contrast a new bit of grammar with

a parallel structurein their own language.

This doesnot necessarilymean that everysinglenew bit of language- every

sound,word, structure,text, and so on - needsto be consciouslyintroduced; or

that everynew unit in the syllabushas to start with a clearly directed

presentation.Moreover, presentationsmay often not occur at the first stageof

learning: they may be given after learners have akeady engagedwith the

LL

1 Presentationsand explanations

languagein question, as when we clarify the meaning of a word during a

discussion,or read aloud a text learnershave previously read to themselves.

The ability to mediate new material or instruct effectivelyis an essential

teaching skill; it enablesthe teacherto facilitate learners'entry into and

understandingof new material, and thus promotes further learning.

Question

If you have learned a foreign langnrage in a course, can ]rou recall a

particular teacher presentation or e:rplanation that facilitated your grasp of

some aspect of this language? Hovv did it help?

What happensin an effectivepresentation?

Attention

The learners are alert, focussing their attention on the teacher and/or the

material to be learnt, and aware that something is coming that they need to take

in. You need to make sure that learnersare in fact attending; it helps if the target

material is perceivedas interestingin itself.

Perception

The learnersseeor hear the target material clearly.This meansnot only making

sure that the material is clearly visible and/or audible in the first place; it also

usually meansrepeating it in order to give added opportunities for, or reinforce,

perception.Finallg it helps to get some kind of responsefrom the learnersin

order to check that they have in fact perceivedthe material accurately:

repetition, for example, or writing.

Understanding

The learnersunderstandthe meaning of the material being introduced, and its

connection with other things they already know (how it fits into their existing

perceptionsof realiry or 'schemata').So you may need to illustrate, make links

with previously learnt material, explain (for further discussionof what is

involved in explaining, seeUnit Three). A responsefrom the learners,again, can

give you valuable feedbackon how well they have understood: a restatementof

concepts in their own words, for example.

Short-term memory

The learnersneed to take the material into short-term memory: to rememberit,

that is, until later in the lesson,when you and they have an opportunity to do

further work to consolidatelearning (seeModule 2: Practiceactiuities).So the

more 'impact' the original presentationhas - for example, if it is colourful,

dramatic, unusual in any way - the better.Note that some learnersremember

better if the material is seen,others if it is heard, yet others if it is associated

with physical movement (visual, aural and kinaestheticinput): theseshould

ideally all be utilized within a good presentation.If a lengthy explanation has

taken place, it helps also to finish with a brief restatementof the main point.

t2

Examples of presentation procedu res

Group task Peer-teaching

One participant chooses a topic or item of information (not necessarily

anything to do with langruage teaching) on which they arrewell informed

and in which they are interested, but which others are likely to be relatively

ignorant about. They prepare a presentation of not more than five minutes,

and then give it.

As many participants as possible give such presentations.

For eachpresentation, pick out and discuss whatwas effective about it,

using where relevant the criteria suggested under What happens in an

effec tive presentation? above.

In Box 1.1 are four accounts,three written by teachersand one by a student,of

four quite different types of presentations.The first describeshow a teacherof

young children in a primary school in New Zealand teachesthem to read and

write their first words; the secondis a recommendationof how to introduce a

short foreign languagedialoguein primary or secondaryschool;the third is an

unusual improvisedpresentationof a particular languagefunction with a class

of adults; and the fourth is the first presentationto a middle-schoolclassof a

play.

soliloquy from a Shakespeare

you

may

help

study the texts; my own commentsfollow.

The task below

Task Griticizing

presentations

For each of the descriptions in Box l.l, consider and/or discuss:

l. lMhat was the aim of the presentation?

2. Hor successful do you think this presentation was' or would be, in

getting students to attend to, perceive, understand and remember the

target material? You may find it helpfitl to refer back to the criteria

described in Unit One.

3. Hovvappropriate and effective wor:ld a similar procednre be for you, in

your teaching situation (or in a teaching situation you are familiar with)?

Comments

This is obviously only a small sampleof the many presentationtechniques

availableto languageteachers.

1. Reading words

The teacherhas basedthis presentationon the students'own choice of

vocabularg derivedfrom their own 'inner worlds'. Sheis thus tapping not only

intellectualbut also personalemotional associationswith the vocabulary;such

associations,it has beenshown by research,have a clear positive effecton

retention, as well as on immediateattention, generalmotivation, and - her main

objective- ability to read the material.

t3

1 Presentationsand explanations

PRESENTATIONS

BOX 1.1: DIFFERENT

Presentation

1:Readingwords

onecanalwaysbeginhimon

... Butif thevocabulary

of a childis stillinaccessible,

commonto anychildin anyrace,a set of wordsbound

the generalKeyVocabulary,

andlateron theircreativewriting,showto be

up with securitythat experiments,

'kiss','frightened',

organically

associated

withthe innerworld:'Mummy','Daddy',

'ghost'.

'Mohi... whatworddoyouwant?'

'Jet

lsmileandwriteit ona stronglittlecardandgiveit to him.

,What is it again?'

'Jet

'Youcanbringit backinthemorning.

Whatdoyouwant,Gay?'

mother.

victimof therespectable

Gayistheclassic

overdisciplined,

bullied

'House,'

shewhispers.

SoI writethat,too,andgiveit intohereagerhand.

(fromSylvia

1980,pp.3F6)

Teacher,Yirago,

Ashton-Warner,

2: Learninga dialogue

Presentation

of the

isto achieve

Themainobiective

at thebeginning

a goodworkingknowledge

...

afterwards

inthetextbook,

or elaborated

dialogue

sothatit canbealtered

andaskthe studentsto repeatit

1. Readout the dialogue,

utterance

by utterance,

in differentformations,

actingoutthe rolesin thefollowingways:

a) togetherin chorus;

b) halfof the classtakeoneroleandtheotherhalftaketheotherrole;

c) onestudentto anotherstudent;

d) onestudent

to therestof theclass...

(fromZoltanDdrnyei,'Exploiting

dynamrcally'

English

textbookdialogues

, Practical

1986,6,4, 15-16)

Teaching

Presentation

3:Accusations

- a trafficjam,a lastminutephonecall,a

It canhappen

to anyone

who commutes

car that won't start- andyou realiseyou are goingto be latefor a lesson...

However,attackbeingthe bestformof defence,I recentlyfounda wayto turnmy

latenessto goodaccount.A full ten minutesafterthe startof the lesson,I strode

intothe classroom

andwroteon the boardin hugeletters

YOU'RE

LATE!

ThenI invitedthe students

to yellat me with allthe venomtheycouldmuster

andwe alllaughed.

SoI wrote:

You'relateagain!

and:

You'realwayslatel

Sowe practised

theseforms.Theyseemedto get a realkickout of puttingthe

the pleasure

of righteous

stressin the rightplace... Whenwe had savoured

most

indignation,

I proposed

that everyone

shouldwrite downthe accusations

poured

outsuchas:

levelled

at him(orher).A richandvariedselection

commonly

Youalwayseatmy sweets!

You'velostthe kevsr

Youhaven'tlostthe keysagain!

'Excuses,

(fromAlisonCoulavin,

Teaching,

1983,4, 2, 31)

Practical

excuses',

English

4: Dramaticsoliloquy

Presentation

... I shallneverforgetMissNancyMcCall,

andthe dayshewhippeda ruleroff my

'ls thisa dagger

whichI

desk,andpointing

it towardsheramplebosom,declaimed,

heartsa-thumping,

in electrified

seebeforeme?'Andtherewe sat,eyesa goggle,

sIence.

(aletterfromAnnaSottoin TheEnglishTeachers'

Journal(lsrael)1986,33)

@CambridgeUniversityPress1996

1,4

Examplesof presentationprocedures

Certainly the use of items suggestedby the learners themselvescan contribute

to the effectivenessof any kind of presentation; however, this idea may be more

difficult to implement in large classes,or where classroomrelationshipsare

more formal.

2. Learninga dialogue

The aim of this presentation is to get students to learn the dialogue by heart for

further practice.

The writer describesa systematicprocedureinvolving initial clear

presentation of the target text by the teacher,followed by varied and numerous

repetitions. The resulting preliminary rote learning of the words of the dialogue

would probably be satisfactory.

But nothing is done to make sure the dialogue is meaningful and interesting

to the students.As it stands,the method of teachingdoesnot provide for

cognitive or affective 'depth': it fails to engagethe students' intellectual or

emotional faculties in any way. [t is important to emphasizelearners'

understanding of the meaning of the dialogue from the beginning, not iust their

learning by heart of the words, and to find ways of stimulating their interest in

it, through the content of the text itself, the teacher'spresentation of it, visual

illustration, or various other means.

3. Accusations

The first two exampleswere accounts of systematicpresentationsof planned

material. This, in contrast, describesan activity improvised by a resourceful

teacherwith a senseof humour and a friendly relationshipwith the class,who

exploits a specificreal-timeeventto teach a languagefunction (accusation,

reproach),with its typical grammar and intonation pafferns.

The presentation seemslikely to produce good perception and initial

learning:not becauseof any carefully planned process,but becauseof the

heightenedattention and motivation causedby the humour (rooted in the

temporary legitimizing of normally 'taboo'verbal aggression)and by the fact

that many of the actual texts are personally relevant to the learners (compare

with PresentationL above).

4. Dramatic soliloquy

This classroomevent is recalled from the point of view of the student, and it was

obviously successfulin attracting the students' attention, getting them to perceive

the material and imprinting it very quickly on their short-term (indeed,longterm!) memory - all these,probablS beingpart of the teacher'sobjectives.As to

understanding:if the classwas native English-spdakingthen one would assumethat

the teacher'sacting and useof props was probably sufficientto cover this aspect

also;foreign languagelearnerswould presumablyneeda little more clarification.

Not everyone,it must be said, has the dramatic ability of the teacherdescribed;

the applicability of this examplefor many of us may be limited! Howeveq if you can

act, or have video material available,dramatic presentationscan be very effective.

15

1 Presentations

and explanations

Unit Three: Explanationsand instructions

'When

introducingnew materialwe often needalsoto giveexplicit descriptions

or definitionsof concepts

or processes,

andwhetherwe canor cannotexplain

suchnewideasclearlyto our students

maymakea crucialdifference

to the

success

or failureof a lesson.Thereis. moreover.

someindicationin research

that learnersseethe ability to explainthingswell asone of the mosrimportant

qualitiesof a goodteacher(see,for example,ITraggandWood,1984).(The

problemof how to explainnew languagewell is perhapsmosrobviousin the

fieldof grammar;for a detailedconsideration

of grammarexplanation,seeUnit

Four of Module 6,Teachinggrammar.)

Oneparticularkind of explanationthat is veryimportantin teachingis

instruction:the directionsthat aregivento introducea learningtask which

entailssomemeasureof independent

studentactivity.The task belowis based

on the experienceof giving instructions,and the following Guidelineson

effectiveexplainingmay be studiedin the light of this experience.Alternatively,

the Guidelines

may bestudiedon their own and tried out in your own teaching.

Task Giving instructions

Sfage1: Experience

If you are cuJrently teaching, notice carefully how you yourself give

instructionsfor a grroup-or pair-work activity in class,and note do,mr

imrnediately afterwards what you did, while the event is still fresh in your

memory.Better,but not alwaysfeasible:aska colleagueto observeyou

and take notes.

Alternatively,within a group of colleagrues:

eachparticipantchoosesan

activity and preparesinstructionson how to do it. The activity may be: a

gamewhich you knor,rhornrto play but others do not; a process(how to

prepare a certarn

certain dish, howto

how to mend orbuild

or build something); or a classroom

procedure.T\voor tluee volunteerparticipantsthen actuallygive the

instructions,and (if practical)the group goeson to startperforming the

activity.

Stage2: Dkcussion

Read the guidelines on giving effective e:rplanationslaid out below, Think

about or discussthemwith colleagues,relating them to the actual

instructionsgiven in stage l. In what ways did theseinstruction$accord

with or differ from the guidelines? Can you now think of ways in which

theseinsfuctions could have been made more effective?

Guidelineson giving effectiveexplanationsand instructions

1. Prepare

Youmayfeelperfectlyclearin your own mindaboutwhat needsclarifying,and

thereforethink that you canimprovisea clearexplanation.

But experience

showsthat teachers'

explanations

areoftennot asclearto theirstudents

asthey

areto themselves!

It is worth preparing:thinkingfor a while aboutthe words

t6

Explanations and i nstructions

you will use,the illustrationsyou will provide, and so on; possiblyevenwriting

theseout.

2. Make sure you have the class's full attention

In ongoing languagepracticelearners'attentionmay sometimesstray; they can

usually make up what they have lost later. But if you are explaining something

essential,they must attend. This may be the only chancethey have to get some

vital information; if they miss bits, they may find themselvesin difficulties later.

One of the implications of this when giving instructions for a group-work task

is that it is advisableto give the instructionsbefore you divide the classinto

groups or give out materials,not after! Once they are in groups, learners'

attention will be naturally directedto eachother rather than to you; and if they

have written or pictorial material in their hands,the temptation will be to look

at it, which may also distract.

3. Present the information more than once

A repetition or paraphraseof the necessaryinformation may make all the

difference:learners'attention wandersoccasionally,and it is important to give

them more than one chanceto understandwhat they have to do. Also, it helps

to re-presentthe information in a different mode: for example,say it and also

write it up on the board.

4. Be brief

Learners- in fact, all of us - have only a limited attention span;they cannot

listen to you for very long at maximum concentration. Make your explanation

as brief as you can, compatiblewith clarity. This meansthinking fairly carefully

about what you can, or should, omit, as much as about what you should

include! In somesituationsit may also mean using the learners'mother tongue,

as a more accessibleand cost-effectivealternativeto the sometimeslengthy and

difficult target-languageexplanation.

5. lllustrate with examples

Very often a careful theoretical explanation only 'comes together' for an

audiencewhen made real through an example,or preferablyseveral.You may

explain, for instance,the meaningof a word, illustrating your explanationwith

examplesof its usein various contexts,relating theseas far as possibleto the

learners'own lives and experiences.Similarly,when giving instructionsfor an

activity, it often helpsto do a 'dry run': an actual demonstrationof the activity

yourself with the full classor with a volunteer student before inviting learners

to tackle the task on their own.

6. Get feedback

'Vfhen

you have finished explaining, check with your classthat they have

understood.It is not enoughjust to ask 'Do you understand?';learnerswill

sometimessay they did evenif they in fact did not, out of politenessor

unwillingness to lose face, or becausethey think they know what they have to

do, but have in fact completelymisunderstood!It is better to ask them to do

somethingthat will show their understanding:to paraphrasein their own

words, or provide further illustrations of their own.

L7

1 Presentations

andexplanations

Furtherreading

Btown,G. A. andArmstrong,S.(1984)'Explanations

andexplaining'in

Wragg,E. C. (ed.)ClassroomTeacbing

Skills,LondonandSydney:Croom

Helm.

(A practicalanalysisof theskill of explainingin theclassroom,

in various

subiects)

Schmidt,R. If. (1990)'Theroleof consciousness

in secondlanguage

learning',

AppliedLinguistics,ll, 2, 129-58.

(A discussionof the importanceof consciousattentionto input in language

learning)

Reference

'Wragg,

E. C. andWood,E. K. (1984)'Pupilappraisals

of teaching'inVragg,

E. C. (ed.),ClassrootnTeaching

Skills,LondonandSydney:CroomHelm

(ch.4).

a

18

lvlodule

2:Practice

activitie

s

Practicecan be roughly definedas the rehearsalof certain behaviourswith the

objective of consolidating learning and improving performance. Language

learnerscan benefitfrom beingtold, and understanding,facts about the

languageonly up to a point: ultimately,they have to acquirean intuitive,

automatizedknowledgewhich will enableready and fluent comprehensionand

And suchknowledgeis normally brought about through

self-expression.

consolidationof learning through practice.This is true of first language

acquisitionas well as of secondlanguagelearning in either 'immersion' or

formal classroomsituations.Languagelearning has much in common with the

learning of other skills, and it may be helpful at this point to think about what

learning a skill entails.

Learning a skill

The processof learning a skill by meansof a courseof instruction has been

defined as a three-stageprocess:verbalization, automatization and autonomy.

At the first stagethe bit of the skill to be learnedmay be focussedon and

definedin words -'verbalized'- as well as demonstrated.Thus in swimming

the instructor will probably both describeand show correct arm and leg

movements;in language,the teachermay explain the meaningof a word or the

rules about a grammaticalstructureas well as using them in context. Note that

the verbalizationmay be elicitedfrom learnersrather than done by the teacher,

and it may follow trial attemptsat performancewhich serveto pinpoint aspects

of the skill that needlearning.It roughly correspondsto 'presentation',as

discussedin the previousmodule.

The teacher then gets the learners to demonstrate the target behaviour, while

monitoring their performance. At first they may do things wrong and need

correcting in the form of further telling and./ordemonstration; later they may do

it right as long as they are thinking about it. At this point they start practising:

performing the skilful behaviouragain and again, usually in exercisessuggested

by the teacher,until they can get it right without thinking. At this point they

may be said to have 'automatized'the behaviour,and are likely to forget how it

was describedverbally in the first place.

Finally they take the set of behavioursthey have masteredand beginto

improve on their own, through further practice activity. They start to speedup

performance,to perceiveor createnew combinations,to 'do their own thing':

they are 'autonomous'. Somepeoplehave calledthis stage'production', but this

I think is a misnomerfor it involvesreceptionas much as production, and is in

t9

2 Practiceactivities

fact simplya moreadvancedform of pracrice,asdefinedat the beginningof this

unit. Learners

now havelittle needof.ateacherexceptperhapsasa supportive

or challengingcolleagueand areready or nearly ready,toperformasmastersof

theskill- or asteachers

themselves.

Thismodelof skill learningis brieflysummarizidin Box2.1.For further

informationon skill theoryin general,seeAnderson,1985:andon skill theorv

appliedto language

learningJohnson(1,99iit.

BOX2.1: SKILLLEARNING

VERBALIZATION

Teacher

describes

and

demonstrates

theskilled

behaviour

to belearned;

perceive

learners

and

understand.

AUTOMATIZATION

Teacher

suggests

exercises;

learners

practise

skillinorder

to acquire

facility,

automatize;

teacher

AUTONOMY

Learners

continue

to

useskillontheir

own,becomlng

moreproficient

and

creative.

montlors.

Question Can you think of a skill - other than swimrning or language - that you

successfullylearned through being taughtit in somekind of course?(If you

carurot,somepossibilities arc suggestedin the Notes, (l).) And can ]rou

identify the stagesdescribed abovein the processof that learning asyou

recall it?

Much languagepracticefalls within the skill-developmentmodel described

above.But someof it doesnot: evenwhereinformationhasnot been

consciouslyverbalizedor presented,learnersmay absorband acquirelanguage

skills and contentthrough direct interactionwith texts or communicativetasks.

In other words, their learningstartsat the automatizationand autonomystages,

in unstructuredfluencypractice.But this is still practice,and essentialfor

successful

learning.

Summary

Practice,then,is the activitythroughwhich languageskillsand knowledgeare

consolidated

andthoroughlymastered.

As such,it is arguablythemost

importantof all the stagesof learning;hencethe mostimportantclassroom

activityof the teacheris to initiateandmanageactivitiesthat providestudents

with opportunitiesfor effectivepractice.

Question Do you agree with the last statement (which erq)ressesmy orvnbelief) or

would you prefer to qualify it?

20

Characteristics of a good practice activity

activity

'whether

or not you think that organizing languagepractice is the most

important thing the teacherdoesin the classroom,you will, I hope, agreethat it

doescontribute significantlyto successfullanguagelearning,and thereforethat

it is worth devoting some thought to what factors contribute to the effectiveness

of classroompractice.

Practiceis usually carried out through procedurescalled 'exercises'or

'activities'.The latter term usually implies rather more learneractivity and

initiative than the former, but there is a large areaof overlap: many procedures

could be definedby either.Exercisesand activitiesmay, of course,relateto any

aspectof language:their goal may be the consolidationof the learning of a

grammaticalstructure,for example,or the improvementof listening,ipeaking,

reading or writing fluenc5 or the memorization of vocabulary.

Try doing the task below beforereading on.

Task Defining effective language practice activities

StageI : Selectingsamp/es

Think of one or more examples of language practice of any kind which you

have experienced either as teacher or as learner, and which you consider

were effective in helping the learners to remember, ,automatize', or

increase their ease of use. Write down brief descriptions of them. (If you

cannot think of any, use the example given in the Notes, (2).)

Stage 2: futalysis

consider: what were the factors, or characteristics, that in your opinion

made these activities effective? Note down, either on your own or in

collaboration with colleagues, at least two such characteristics - more if

you can.

Sfagre3-'Dlbcusslon

Now compare what you have with my list below. Probably at least some of

your ideas will be similar to mine, though you may have expressed them

differently. If I have suggested ideas that are new to you, d.oyou agree with

them? \Mhat would you include that I have not?

Characteristics of effective lang uage practice