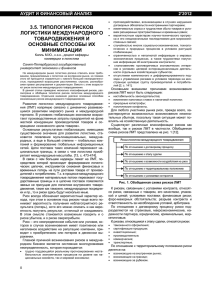

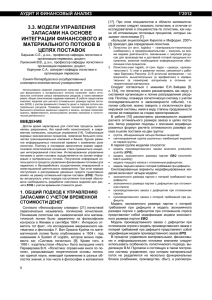

The Effect of Logistics Service Quality on Customer Loyalty through Relationship Quality in the Container Shipping Context Author(s): Hyun Mi Jang, Peter B. Marlow and Kyriaki Mitroussi Source: Transportation Journal , Vol. 52, No. 4 (Fall 2013), pp. 493-521 Published by: Penn State University Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/transportationj.52.4.0493 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/transportationj.52.4.0493?seq=1&cid=pdfreference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Penn State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Transportation Journal This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Effect of Logistics Service Quality on Customer Loyalty through Relationship Quality in the Container Shipping Context Hyun Mi Jang, Peter B. Marlow, and Kyriaki Mitroussi Abstract The objective of this research is to explore the role of logistics service quality in generating shipper loyalty, considering relationship quality in the unique context of container shipping. This is to fill the gaps revealed in the current understanding of ocean carrier–shipper relationships, particularly the lack of studies attempting to investigate shippers’ future intentions to use the same carrier as opposed to the previous studies that focused on carrier selection criteria or on shippers’ satisfaction with the service attributes. Soft concepts such as customer loyalty and logistics service quality have been increasingly explored in a variety of industries to offer further insight into the relationship issues. However, it was discovered that relatively few studies on this topic have been conducted in the context of maritime transport. The theoretical model is tested on data collected through a postal questionnaire survey of 227 freight forwarders in South Korea. Structural equation modeling (SEM) is employed to rigorously examine relationships among the extensive set of key variables simultaneously in a holistic manner. The findings demonstrate that container shipping lines should develop a high level of logistics service quality as well as relationship quality in order to attain higher (beyond mere satisfaction) levels of shippers’ loyalty. Keywords Logistics service quality, customer loyalty, relationship quality, container shipping, structural equation modeling Hyun Mi Jang Lecturer Dongseo University Email: jangh0911@gdsu.dongseo.ac.kr Peter B. Marlow Associate Dean/Professor Logistics and Operations Management Cardiff University Kyriaki Mitroussi Senior Lecturer Logistics and Operations Management Cardiff University Transportation Journal, Vol. 52, No. 4, 2013 Copyright © 2013 The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 493 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM 494 / TRANSPORTATION JOURNAL™ Introduction Today’s competitive environment is characterized by shorter product and technology life cycles, the globalization of markets, and high uncertainties in supply and demand. Operated in this environment, shippers, namely manufacturers and retailers, have globalized their production systems, adopted a “Just-in-Time” philosophy, and outsourced a number of activities with the aim of minimizing total costs and maximizing customer value. This widespread adoption of the supply chain management approach by shippers is affecting the crucial success factors in transport and logistics, both for individual logistics service providers, such as logistics specialists, freight forwarders and carriers, and for clusters of organizations, such as ports (Carbone and Gouvernal 2007). Despite the diversity of transport services, maritime transport in the global freight trade is of major significance in terms of tonnage as it handles approximately 90 percent of the global total tonnages. In particular, the importance of container liner shipping to international trade cannot be ignored as 60 percent of general cargo is globally containerized (Wang 2006). Acciaro emphasized the significance of this industry by saying “Without the development of containerization and the liner shipping industry, globalization could not have taken place the way we know it nowadays” (2010, p. 55). As the role of container shipping lines has evolved in global supply chains, they are required to pay more attention to managing relationships with their partners, particularly with shippers. Shippers are spending more time finding qualified carriers to help increase market share as well as achieve higher levels of customer satisfaction. Qualified carriers therefore must meet more stringent criteria relating to employee, equipment, facility capability, and system compatibility with the highest performance and pricing consistency. This is supported by the findings of Carbone and Gouvernal’s (2007) study conducted with maritime experts, which shows that “selecting the key logistics service providers” and “establishing long-term relationships with customers” are vital for container shipping lines to achieve a higher degree of supply chain integration. Evangelista (2005) also pointed out that container shipping lines are increasingly forced to focus on shippers’ demand first to attract their attention, meet their expectations, and further develop stronger connections with them. Considering the significance of the containerized trade served by shipping lines to global economies and the recent changes and severe competition in maritime transport, it is crucial for container shipping lines to put more effort into utilizing their logistics service capabilities for strengthening the long-term relationships with their shippers to attain TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 494 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM Jang, Marlow, Mitroussi: The Effect of Logistics Service Quality \ 495 their loyalty. However, as compared to other industries, relatively few studies have been conducted on these relationship issues, which focus on customer loyalty together with logistics service quality in the container shipping context. It was noted that many studies in maritime transport have been conducted to evaluate the importance or satisfaction shippers attached to their ocean carriers (e.g., Brooks 1990; Kent and Parker 1999; Lu 2003a; Matear and Gray 1993). From these it is difficult to understand whether they can continue the business with existing customers as sometimes satisfied shippers leave for other ocean carriers, while dissatisfied shippers stay with them for several reasons. In other words, simply satisfying shippers does not guarantee that they are always loyal. In contrast, in marketing and supply chain literature, a multitude of studies have been conducted to explore customer loyalty in depth with other important concepts such as relationship quality and the switching barrier (e.g., Chen and Wang 2009; Davis and Mentzer 2006; Liu, Guo, and Lee 2011; Rauyruen and Miller 2007). Moreover, the simple investigation would have produced limited results since other factors may influence customer loyalty, and also there are different kinds of customer loyalty such as spurious loyalty, which is different from true loyalty. Therefore, a more complex link needs to be examined, including factors such as relationship quality, to produce more sophisticated results. Against this background, the objective of this research is to identify the effect of logistics service quality in creating customer loyalty through relationship quality for better understanding of the relationship issues in the context of container shipping. By exploring these concepts simultaneously and also dividing them into several subconstructs, more complexity is added in understanding of ocean carrier–shipper relationships. It is important to provide empirical evidence to improve container liners’ understanding of the relationship issues with their shippers. The findings can also be utilized to segment the shipper groups according to their loyalty types so that their logistics service capabilities are strategically managed for each group and strong relationships are pursued with shippers who are more loyal to them. The rest of this article consists of four sections. The next section provides a review of the literature on key concepts to produce research hypotheses. We then describe the methodological context, including data collection, analysis methods, sample, and measurement of variables. The discussion of results and findings of the survey follows. Conclusions drawn from the analyses and strategic implications for container liner shipping companies are discussed in the final section. TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 495 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM 496 / TRANSPORTATION JOURNAL™ Theoretical Background Fundamentals and Measurement of Logistics Service Quality In the context of maritime transport, as global competition has intensified over the past decades, container shipping lines are facing more sophisticated demands and increased expectations from shippers. According to Gibson, Sink, and Mundy (1993), shippers’ transport management has shifted from selecting different carriers for each service and/or route to negotiating with fewer carriers that provide a wide range of services under long-term relationships. In addition, the primary value sought by shippers has been diverted from “price” to “service quality.” Baird (2003) indicated that shippers actually demand a total value-added service package instead of one or two services from carriers. Consequently, integrated logistics services provided by container shipping lines have become highly significant when selecting carriers. To understand how the logistics service has been examined in maritime transport-related studies, 23 studies published since 1990 have been examined from three perspectives: 12 studies from a shipper’s perspective, 5 studies from a carrier’s perspective, and 6 studies from both carriers and shippers’ perspectives to identify their service perception gap (e.g., Brooks 1990; Casaca and Marlow 2005; Lu 2003a, 2003b). From this comprehensive review, “prompt response to problems and complaint” was discovered to be used most frequently in maritime transport studies, followed by “on-time pick-up and delivery” and “knowledge and courtesy of sales personnel.” However, it should be noted that service priorities differ between shippers depending on the nature of their cargoes and businesses. Shippers’ requirements are also changing over time. As such, even though a number of empirical studies have been conducted to select and evaluate logistics service in maritime transport, each shows different results. In an effort to evaluate logistics service, marketing tools using customer perceptions of provider performance have begun to be applied in logistics research (Stank, Goldsby, and Vickery 1999). Logistics service quality (LSQ) is an instrument to measure customer perceptions of the value created for them by logistics services. Logistics service can be used to create customer and supplier value through service performance, influence satisfaction and customer loyalty, and increase market share (Daugherty, Stank, and Ellinger 1998). In addition, the importance of two aspects of logistics service has been widely underlined in logistics and supply chain research (e.g., Davis-Sramek et al. 2009): operational logistics service quality (OLSQ) and relational logistics service quality (RLSQ). TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 496 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM Jang, Marlow, Mitroussi: The Effect of Logistics Service Quality \ 497 Conceptualization and Operationalization of Relationship Quality Due to the uncertainty stemming from the complexity of the logistics services provided by container shipping lines, it is of major importance to manage relationships with shippers effectively and maintain high-quality relationships to reduce uncertainty. Relationship quality was shown to be a better predictor of customer loyalty than service quality. Furthermore, the intangibility of relationship quality makes it difficult to be duplicated by competitors, thus providing a sustainable competitive advantage to the firm (Roberts, Varki, and Brodie 2003). The concept of relationship quality arises from theory and research in the field of relationship marketing and has been employed extensively in logistics literature (e.g., Fynes, Voss, and de Búrca 2005; Panayides and So 2005) and marketing literature to investigate relationships between buyers and sellers (e.g., Boles, Johnson, and Barksdale 2000) and customers and service personnel/firms (e.g., Hennig-Thurau, Gwinner, and Gremler 2002). Nonetheless, it was found that, except for a study by Bennett and Gabriel (2001), research has yet to address the relationship quality in the context of maritime transport. Relationship quality has generally referred to an overall construct based on all previous experiences and impressions the customer has had with the service provider (Hennig-Thurau and Klee 1997). Previous research has revealed that constructs of relationship quality have a direct impact on customer retention, customer loyalty, and long-term orientation between firms. In addition, relationship quality plays a vital role in reducing uncertainty in many service contexts and the potential of service failures customers face (Qin, Zhao, and Yi 2009). Although there is a lack of consensus in defining and measuring relationship quality due to the fact that a variety of relationships exist across the range of customers and business markets, relationship quality, similar to service/product quality, can best be operationalized as a higher-order and multidimensional construct. From the previous studies, it can be inferred that “satisfaction,” “trust,” and “commitment” seem to be most commonly utilized as dimensions of relationship quality. Fundamentals and Measurement of Customer Loyalty It is becoming clear that customer loyalty, mainly with regard to relationships between suppliers and their customers, is a key construct in marketing and service-related research. While a considerable number of studies have been conducted, customer loyalty is still too complex to be defined in a simple way (Jacoby and Kyner 1973). In a review of the literature, Davis-Sramek, Mentzer, and Stank (2008) argued that more TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 497 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM 498 / TRANSPORTATION JOURNAL™ than 20 different definitions of customer loyalty had been identified, most of which were described in terms of the method of measurement, rather than an explicit explanation of what it is and what it means. For instance, Maignan, Ferrell, and Hult (1999, 459) delineated it as “the non-random tendency displayed by a large number of customers to keep buying products from the same firm over time and to associate positive images with the firm’s products.” Davis-Sramek, Mentzer, and Stank (2008, 785) summarized that “customer loyalty has been defined in terms of repeat purchasing, a positive attitude, long-term commitment, intention to continue the relationship, expressing positive word-of-mouth, likelihood of not switching, or any combination of these.” This richness of definitions demonstrates that the researcher is required to decide the particular dimensions of customer loyalty and the way to deal with their interrelatedness when conducting empirical studies. Oliver (1999) pointed out that customer loyalty evolves and consists of four stages: cognitive loyalty, affective loyalty, conative loyalty, and action loyalty. Each stage has its own vulnerabilities, depending on the nature of the customer’s commitment. Previous literature suggests that there are different types of customer loyalty, and so the phrase “customer loyalty” may refer to different things. According to Jones and Sasser (1995), there are two kinds of customer loyalty: true long-term and false loyalty, of which the latter makes customers stay loyal when they are not. False loyalty is attributed to various reasons, such as high switching costs, government regulations that limit competition, proprietary technology that restricts alternatives, and strong loyalty-promotion programs. To clarify customers’ true loyalty, previous studies highlighted the fact that attitudinal loyalty should be combined with behavioral loyalty (e.g., Oliver 1999). Following this stream, thus, customer loyalty is proposed as a composite concept combining both behavioral and attitudinal loyalty in this study. Research Hypotheses A conceptual model is developed to determine how and to what extent logistics service quality (LSQ) and relationship quality (RQ) toward customer loyalty (CL) are related. By dividing these major concepts into subconstructs (i.e., LSQ—operational logistics service quality and relational logistics service quality, RQ—satisfaction, trust and commitment, and CL—attitudinal loyalty and behavioral loyalty), more sophisticated interrelationships can be explored for the first time in the container shipping context. Before establishing a research model, the definition of each construct is described in table 1 to avoid possible confusion. The assumed relationships among those key concepts are described in figure 1. TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 498 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM Jang, Marlow, Mitroussi: The Effect of Logistics Service Quality \ 499 The theoretical foundations for the relationships depicted in figure 1 are summarized by the following 16 hypotheses. First, logistics service quality has two dimensions that together can create a strong incentive for container shipping lines to gain customer loyalty: OLSQ and RLSQ. The first dimension of logistics service quality, OLSQ is an internal or operations-oriented dimension, involving such features as on-time delivery and short transit time. The second dimension of logistics service quality, RLSQ reflects an external or market-oriented dimension, which involves the firm’s ability to sense and understand customer needs through relationships created by customer service personnel. Stank, Goldsby, and Vickery (1999) argued that these two constructs are the co-varying antecedents of satisfaction and loyalty. This means firms that tend to be more progressive operationally also tend to be more aware of customer needs and wants, and vice versa. In this study, the model depicted in figure 1 portrays RLSQ as an Table 1/Definition of Key Concepts Operational logistics service quality Davis-Sramek, Mentzer, and Stank 2008, p. 783 The perceptions of logistics activities performed by service providers that contribute to consistent quality, productivity, and efficiency Relational logistics service quality Davis-Sramek, Mentzer, and Stank 2008, p. 783 The perceptions of logistics activities that enhance service firms’ closeness to customers, so that firms can understand customers’ needs and expectations and develop processes to fulfill them Satisfaction Howard and Sheth 1969, p. 145 The buyer’s cognitive state of being adequately or inadequately rewarded for the sacrifices he has undergone Trust Schurr and Ozanne 1985, p. 940 The belief that a partner’s word or promise is reliable and a party will fulfill his/her obligations in the relationship Commitment Dwyer, Schurr, and Oh 1987, p. 19 An implicit or explicit pledge of relational continuity between exchange partners Attitudinal loyalty Chaudhuri and Holbrook 2001, p. 83 The level of customers’ psychological attachments and attitudinal advocacy toward the service provider/supplier Behavioral loyalty Chaudhuri and Holbrook 2001, p. 83 The willingness of average business customer to repurchase the service and the product of the service provider and to maintain a relationship with the service provider/supplier TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 499 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM 500 / TRANSPORTATION JOURNAL™ Figure 1 Main Research Model antecedent to OLSQ because RLSQ allows container shipping lines to gain insights into what shippers need and want. This proposition was supported in the supplier-buyer relationship studies (e.g., Stank et al. 2003) and manufacturer-retailer relationship studies (e.g., Davis-Sramek, Mentzer, and Stank 2008). Therefore, this link will be tested in the container shipping context. Hypothesis 1. In the carrier-shipper relationship, RLSQ has a positive impact on OLSQ. Empirical studies in marketing, operations, and logistics show considerable support for links between operational and relational performance and customer satisfaction (e.g., Davis-Sramek et al. 2009). In particular, in the logistics and supply chain context, both operational and relational performance of logistics service was proved to positively affect customer satisfaction. Satisfaction was revealed as one of the dimensions of relationship quality. Thus, considering only satisfaction with logistics service quality may provide limited results. In addition, from the interviews, trust and commitment, unexplored concepts in maritime transport, were revealed to be important due to the uncertainty in maritime transport. Accordingly, relationship quality comprising satisfaction, trust, and commitment will be investigated. Hypothesis 2. In the carrier-shipper relationship, RLSQ has a positive impact on SA. TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 500 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM Jang, Marlow, Mitroussi: The Effect of Logistics Service Quality \ 501 Hypothesis 3. In the carrier-shipper relationship, RLSQ has a positive impact on TRU. Hypothesis 4. In the carrier-shipper relationship, RLSQ has a positive impact on COM. Hypothesis 5. In the carrier-shipper relationship, OLSQ has a positive impact on SA. Hypothesis 6. In the carrier-shipper relationship, OLSQ has a positive impact on TRU. Hypothesis 7. In the carrier-shipper relationship, OLSQ has a positive impact on COM. When analyzing future intentions, Garbarino and Johnson (1999) argued that three factors of relationship quality, namely overall customer satisfaction, trust, and commitment, can be separately identified and interacted differently for different types of customers. Specifically, they hypothesized that overall customer satisfaction may influence trust and, in turn, trust may impact commitment. These two paths were confirmed to be significant. These relationships were also supported by Caceres and Paparoidamis’s study (2007). In addition, trust was emphasized to play a major role in creating commitment in the relationship process (Morgan and Hunt 1994). As there were no empirical studies which investigate these inter-relationships in the context of container shipping transport, they will be tested as follows: Hypothesis 8. In the carrier-shipper relationship, SA has a positive impact on TRU. Hypothesis 9. In the carrier-shipper relationship, TRU has a positive impact on COM. The main research model includes relationship quality as a determinant of both aspects of customer loyalty. Customer loyalty is proposed as a composite concept combining both attitudinal loyalty and behavioral loyalty to enable maximum explanatory power of the construct and prevent limited results. Relationship quality together with switching barriers was proven to have positive effects on customer loyalty (Liu, Guo, and Lee 2011). Rauyruen and Miller (2007) studied how relationship quality can influence customer loyalty in the business-to-business (B2B) context through two levels of relationship quality (relationship quality with employees of the supplier and relationship quality with the supplier itself as a whole) that comprises four different dimensions (i.e., service quality, satisfaction, trust, and commitment). Given the theory and evidence of past research on relationship quality and customer loyalty, it is possible to lay out the following six hypotheses. TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 501 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM 502 / TRANSPORTATION JOURNAL™ Hypothesis 10. In the carrier-shipper relationship, SA has a positive impact on AL. Hypothesis 11. In the carrier-shipper relationship, TRU has a positive impact on AL. Hypothesis 12. In the carrier-shipper relationship, COM has a positive impact on AL. Hypothesis 13. In the carrier-shipper relationship, SA has a positive impact on BL. Hypothesis 14. In the carrier-shipper relationship, TRU has a positive impact on BL. Hypothesis 15. In the carrier-shipper relationship, COM has a positive impact on BL. Customer loyalty is conceptualized as the causal relationship between attitudinal and behavioral loyalty. Dick and Basu (1994) viewed customer loyalty as an attitude-behavior causal relationship in their framework. Bandyopadhyay and Martell (2007) also proved that behavioral loyalty is affected by attitudinal loyalty across many brands of the toothpaste category. In the same way, whether attitudinal loyalty truly leads to the behavioral loyalty in the container shipping context will be examined. Hypothesis 16. In the carrier-shipper relationship, AL has a positive impact on BL. Methodology Data Collection and Analysis Methods This empirical research employs a questionnaire survey for data collection. By using a survey strategy, a large amount of data from a sizable population can be collected in a highly economical way. To select the sample for a questionnaire survey, it should be decided whether both types of customers in container shipping, beneficial cargo owners (BCOs) and freight forwarders, should be included as previous studies affirmed that BCOs and freight forwarders have different priorities in terms of criteria for not only carrier selection but also mode choice and port selection (e.g., D’este and Meyrick 1992). In addition, there is a possibility of conflict in transportation channels since various participants have their own objectives. In this regard, it was determined to involve only one customer type. Based on both the literature review and semi-structured interviews, freight forwarders, the intermediaries as both the decision-makers and the buyers in maritime transport, are selected as the survey samples. This is because, compared to shippers, they are more service-oriented in their TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 502 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM Jang, Marlow, Mitroussi: The Effect of Logistics Service Quality \ 503 decision making (D’este and Meyrick 1992), and have more expertise and experience over wider range of traffic (Tongzon 2002). Murphy and Daley (2001) described freight forwarders as trade specialists capable of providing a variety of functions to facilitate the movement of shipments. Most studies demonstrate that direct shippers or carriers were mainly employed as a sample in maritime transport–related studies, but intermediaries, particularly freight forwarders who play a central role in choosing transportation, were relatively ignored in the marketplace. Martin and Thomas (2001) noted that container shipping lines will continue to regard freight forwarders as their key customer base. To analyze the data gathered, structural equation modeling (SEM) is considered as the most appropriate analytical tool. SEM gives a deeper understanding of the causal relationships of multiple constructs in the conceptual model as applied in logistics studies, such as Vickery et al. (2004) and Lin et al. (2005). Sample Ocean freight forwarders in South Korea were the samples of the questionnaire survey. The number of freight forwarders varies slightly with different organizations and different materials. This may be attributed to the fact that the characteristics of relatively easy entry and exit from this industry by many small- and medium-sized freight forwarders make it difficult to estimate the exact number of freight forwarders. This was supported by our semi-structured interviews and the previous studies by Bird and Bland (1988) and Sakar (2010). Considering this, nonprobability sampling was deemed to be appropriate for the current study. Specifically, convenience and purposive sampling were selected for the present study. Convenience sampling has been chosen due to the easy accessibility and proximity to the researcher, and purposive sampling because it uses the knowledge and experience of the researcher to obtain a representative sample of the population based on the researcher’s evaluation. A total of 1,017 ocean freight forwarders were selected from the 2011 Maritime and Logistics Information Directory published by the Korea Shipping Gazette as a sample for the empirical research. The questionnaire survey was conducted over one month (February 2011). The five-page Korean language questionnaire, accompanied by a cover letter, a letter of recommendation, and a postage-paid return envelope, was mailed to the potential respondents. Table 2 illustrates the response rate of the mail survey. The total response rate was 23.21 percent (227/978), which is higher than those of the previous empirical studies. To check any potential nonresponse bias, the nonresponse bias was estimated using procedures recommended by Armstrong and Overton (1977) and Lambert TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 503 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM 504 / TRANSPORTATION JOURNAL™ Table 2/Questionnaire Response Rate Total 1 Number distributed 1,017 2 Nondeliverable 39 3 Effectively delivered (1 − 2) 978 4 Total responses 233 5 Discard 6 Effective questionnaires (4 − 5) 7 Response rate 6 227 23.21% and Harrington (1990). The last quartile of respondents was assumed to be most similar to nonrespondents as their replies took the longest time and most effort to obtain. The responses given by the last quartile were compared with those provided by the first quartile, and the results show that a nonresponse bias is not a concern in this study. The characteristics of the respondents were analyzed by identifying their position, and work experience in the ocean freight forwarding industry and in the current firm, as revealed in table 3. The analysis demonstrates a variety of demographic backgrounds among the respondents, and significant variance in response was also noted. Even though it was proved that almost half of the respondents have a lower position in their firm and fewer than six years of work experience both in the industry and the current firm, it would be appropriate to include them in this present study as they are the people who directly deal with liner shipping companies. This implies that they had sufficient business experiences with the liner shipping companies that allow them to provide reliable and accurate answer to the survey questions. Tables 4 and 5 summarize the results of eight questions relating to the respondents’ firms. Significant variance in responses of their firm information was identified, suggesting that the sample is representative of the population. Measures The measurement items for evaluating logistics service quality, relationship quality, and customer loyalty were mainly adopted from prior research and supplemented with a result of the qualitative interviews. A comprehensive review of the literature and interviews with practitioners were used to ensure the accuracy and validity of the questionnaire instrument. Each variable was measured using a five-point Likert scale, where 1 corresponds to “strongly disagree” and 5 “strongly agree.” The final measurement items employed in this study are presented in the appendix. TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 504 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM Jang, Marlow, Mitroussi: The Effect of Logistics Service Quality \ 505 Table 3/Overall Profile of Survey Respondents Total Respondent Variable Category Frequency Percentage Cumulative 1–3 55 24.2% 24.2% 4–6 56 24.7 48.9 7–9 33 14.5 63.4 10–12 41 18.1 81.5 13–15 20 8.8 90.3 16–18 6 2.6 93.0 19–21 10 4.4 97.4 22–24 4 1.8 99.1 25–27 1 0.4 99.6 28–30 – – 100.0 Work experience in the industry (years) Mean: 8.03 S.D.: 5.80 31–33 1 0.4 227 100.0% 1–3 92 40.5% 40.5% 4–6 74 32.6 73.1 Sum Work experience in the company (years) Mean: 5.18 S.D.: 4.04 7–9 31 13.7 86.8 10–12 19 8.4 95.2 13–15 6 2.6 97.8 16–18 2 0.9 98.7 19–21 1 0.4 99.1 22–24 1 0.4 99.6 100.0 25–27 1 0.4 227 100.0% Vice president or above 13 5.7% 5.7% Director/vice director 11 4.8 10.6 General manager 22 9.7 20.3 Assistant manager/manager 49 21.6 41.9 Section manager/ supervisor/chief 79 34.8 76.7 Staff 51 22.5 99.1 Other 2 0.9 100.0 227 100.0% Sum Respondents’ position Sum TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 505 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM 506 / TRANSPORTATION JOURNAL™ Table 4/Overall Profile of Survey Respondents’ Firms (1) Total Respondents’ Firm Variable Category Company age (years) Percentage a Cumulative Fewer than 5 years 22 9.8% 9.8%a 5–10 years 50 22.3a 32.1a 11–15 years 45 20.1a 52.2a 44 19.6 a 71.9a a 89.3a 16–20 years 21–25 years 39 17.4 More than 25 years 24 10.7a Missing 3 100.0a 227 100.0%a Local firm 199 88.8%a 88.8%a Foreign-owned firm 21 9.4a 98.2a Foreign-local firm 3 1.3a 99.6a 1 a Sum Ownership pattern Frequency Other Missing Fewer than 5 19 8.4% 8.4% 5–10 17 7.5 15.9 11–20 43 18.9 34.8 21–40 28 12.3 47.1 41–50 15 6.6 53.7 51–100 26 11.5 65.2 100.0 More than 100 79 34.8 227 100.0 Less than 3 35 17.3%a 17.3%a 3–5 57 28.2a 45.5a 27 a 13.4 58.9a 11–15 11 5.4 a 64.4a 16–20 22 10.9a 6–10 21–25 1 75.2a 0.5 a 75.7a a 81.2a 26–30 11 5.4 More than 30 38 18.8a Missing Sum 3 100.0a Sum Starting capital invested in the company (100 million Korean Won) 100.0a 227 Sum Full-time employees 0.4 100.0a 25 227 100.0a TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 506 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM Jang, Marlow, Mitroussi: The Effect of Logistics Service Quality \ 507 Total Respondents’ Firm Variable Company location Category Frequency Percentage Cumulative Seoul 105 46.5%a 46.5%a Busan 97 42.9a 89.4a Incheon Daegu 0.4a 96.0a 2.7a 98.7a 3 a Yes 1.3 100.0a 1 227 100.0a 126 57.0a a No 95 43.0 Missing 6 100.0a 57.0a 100.0a Sum 227 11–20% 8 4.0a 4.0a 21–30% 25 12.4a 16.3a 31–40% 23 11.4a 27.7a 34 16.8 a 44.6a a 62.9a 41–50% 51–60% 37 18.3 61–70% 36 17.8a 80.7a 22 10.9 a 91.6a 14 6.9 a 91–100% 3 1.5a Missing 25 Sum 227 81–90% a 95.6a 1 71–80% Sum 0.9 6 Missing The percentage of the business with the primary liner shipping company in terms of container volumes 94.7a a Gwangju Sum Sum 2 5.3 Gyeonggi-do Gyeongsang-do Service contracts/ agreements 12 a 98.5a 100.0a 100.0a Valid percent allowing for missing data. Results of Analyses Perceptions on Logistics Service Quality, Relationship Quality, and Customer Loyalty Table 6 demonstrates that all the mean values of the 14 items for logistics service quality were above 3.0. For the nine-item scale used to measure relationship quality, the overall mean of each subconstruct is 3.54 for satisfaction, 3.39 for trust, and 3.6 for commitment. The overall mean of relationship quality, 3.51, suggests that the respondents assess their relationship quality with their primary liner shipping company positively. In addition, the overall mean of behavioral loyalty (mean = 3.7) is revealed to be higher TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 507 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM 508 / TRANSPORTATION JOURNAL™ Table 5/Overall Profile of Survey Respondents’ Firms (2) Total Respondents’ Firm Variable Major service routes Category Frequency Percentage Cases (%) North America 87 13.6 38.5% Europe 101 15.8 44.7 Middle East 50 7.8 22.1 Central and South America 43 6.7 19.0 Oceania 35 5.5 15.5 Southeast Asia 113 17.7 50.0 Japan 73 11.4 32.3 China 113 17.7 50.0 Russia 14 2.2 6.2 Africa 10 1.6 4.4 Other Sum 1 0.2 0.4 640 100.0 283.2 than that of attitudinal loyalty (mean = 3.34). From this, it can be inferred that the respondents tend to be dedicated to their primary liner shipping company behaviorally rather than being emotionally attached to them. Measurement Analysis The data was analyzed in accordance with a two-step method where the measurement model is first evaluated separately from the full structural equation model. The measurement models are tested using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) by means of Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS) to confirm construct unidimensionality, reliability, and validity (see table 7). The relations between the observed variables and the underlying variables were postulated a priori based on both previous theoretical and empirical studies and semi-structured interviews. According to the analysis, there were some low standardized regression weights, indicating inappropriate variables. As a result, six items that had regression weights of lower than 0.50 were deleted from LSQ , two items from RQ , and four items from CL. Within this analysis, both theoretical and statistical considerations were incorporated as advised by Anderson and Gerbing (1988). The adjusted x2(x2/df) and other goodness-of-fit statistics in table 7 indicate that the model achieved a good fit to the observed data, thus satisfying the conditions of unidimensionality. All standardized regression weights are greater than 0.60 and the critical ratios are significant p = 0.001, except for TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 508 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM Jang, Marlow, Mitroussi: The Effect of Logistics Service Quality \ 509 Table 6/Descriptive Statistics for Key Concepts Response scale (%) Construct Operational logistics service quality Relational logistics service quality Satisfaction Trust Commitment Attitudinal loyalty Behavioral loyalty Indicators (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) Mean SD OLSQ01 0.4% 11.0% 34.4% 44.5% 9.7% 3.52 0.83 OLSQ02 0.4 6.6 44.1 41.0 7.9 3.49 0.76 OLSQ03 0.9 4.4 40.5 45.8 8.4 3.56 0.75 OLSQ04 0.4 9.3 34.4 48.5 7.5 3.53 0.78 OLSQ05 0.0 5.7 29.1 56.8 8.4 3.68 0.71 OLSQ06 0.4 9.4 42.2 42.6 5.4 3.43 0.76 OLSQ07 0.9 10.1 41.9 39.6 7.5 3.43 0.81 RLSQ08 0.9 16.7 37.9 40.5 4.0 3.30 0.82 RLSQ09 0.9 7.1 45.3 42.7 4.0 3.42 0.72 RLSQ10 0.9 9.7 37.4 43.2 8.8 3.49 0.82 RLSQ11 0.4 6.7 36.0 48.0 8.9 3.58 0.76 RLSQ12 2.6 16.3 45.4 29.5 6.2 3.20 0.88 RLSQ13 3.5 17.6 38.8 35.7 4.4 3.20 0.90 RLSQ14 0.9 10.1 40.5 43.2 5.3 3.42 0.78 SA01 0.0 4.9 40.3 48.7 6.2 3.56 0.69 SA02 0.4 4.4 45.1 44.7 5.3 3.50 0.69 SA03 0.0 5.3 40.5 47.1 7.0 3.56 0.70 TRU04 0.4 7.9 42.3 41.9 7.5 3.48 0.77 TRU05 0.0 5.7 44.9 44.1 5.3 3.49 0.69 TRU06 1.8 14.5 48.9 31.7 3.1 3.20 0.79 COM07 0.4 3.5 32.6 52.4 11.0 3.70 0.73 COM08 1.3 6.6 38.8 45.8 7.5 3.52 0.78 COM09 0.4 7.9 34.4 48.5 8.8 3.57 0.78 AL01 1.3 11.6 44.0 38.7 4.4 3.33 0.79 AL02 1.3 13.2 52.4 30.8 2.2 3.19 0.74 AL03 1.3 5.8 40.6 46.4 5.8 3.50 0.75 BL04 0.0 3.1 34.2 54.7 8.0 3.68 0.67 BL05 0.4 2.2 29.2 56.2 11.9 3.77 0.70 BL06 0.0 7.1 33.6 47.3 11.9 3.64 0.78 Note: OLSQ = Operational logistics service quality; RLSQ = Relational logistics service quality, SA = Satisfaction; TRU = Trust; COM = Commitment, AL = Attitudinal loyalty; BL = Behavioral loyalty one item in TRU construct with loading of 0.55 and one item in AL construct with loading of 0.59, both of which, however, are significant at the 0.001 significant level and do not appear to harm the overall model fit. This demonstrates adequate convergent validity. The values of Cronbach’s alpha (> 0.7), composite reliability (> 0.7), average variance extracted (AVE > 0.5) indicate that construct TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 509 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM 510 / TRANSPORTATION JOURNAL™ Table 7/CFA Results for Measurement Model Construct OLSQ RLSQ SA TRU COM AL BL Indicators Standardized Regression Weight Critical Ratio (t-value) Composite Reliability Average Variance Extracted Cronbach’s Alpha OLSQ01 0.62 8.83*** 0.91 0.58 0.85 OLSQ02 0.64 9.04*** OLSQ03 0.75 10.64*** OLSQ04 0.72 10.18*** OLSQ05 0.63 8.92*** OLSQ06 0.60 8.54*** OLSQ07 0.73 – RLSQ08 0.70 10.52*** 0.92 0.61 0.88 RLSQ09 0.68 10.10*** RLSQ10 0.75 11.26*** RLSQ11 0.75 11.20*** RLSQ12 0.76 – RLSQ13 0.67 9.91*** 0.93 0.82 0.86 0.88 0.71 0.77 0.90 0.75 0.83 0.82 0.60 0.72 0.88 0.72 0.79 RLSQ14 0.69 10.35*** SA01 0.83 13.80*** SA02 0.83 13.72*** SA03 0.81 – TRU04 0.84 – TRU05 0.86 14.33*** TRU06 0.55 8.37*** COM07 0.79 12.53*** COM08 0.84 – COM09 0.74 11.70*** AL01 0.59 7.90*** AL02 0.60 8.08*** AL03 0.83 – BL04 0.85 10.16*** BL05 0.73 9.40*** BL06 0.69 – Overall Goodness-of-fit Indices x2/df = 1.63 CFI = 0.94; TLI = 0.93; SRMR = 0.03 RMSEA = 0.05 validity was confirmed for the measurement models. Table 8 displays that the correlation coefficients among the latent constructs do not exceed the cutoff point of 0.85 advised by Kline (2005). The comparison between AVE and correlations also provides evidence of discriminant validity between the constructs. TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 510 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM Jang, Marlow, Mitroussi: The Effect of Logistics Service Quality \ 511 Hypotheses Tests The full hypothesized structural model is illustrated in figure 2. In this figure, the error terms associated with observed and latent variables are omitted for simplicity. Table 9 presents the parameter estimates of the full structural model and exhibits the SEM results of the hypotheses testing. The fit indices (x2/df = 1.67; CFI = 0.93; TLI = 0.92; SRMR = 0.03; RMSEA = 0.05) are acceptable, implying that the estimated model has achieved a good fit. According to table 9, all paths specified in the hypothesized model were found to be statistically significant at different significance levels, except for the following five hypothesized paths: OLSQ→TRU, RLSQ→COM, SA→AL, SA→BL, and TRU→BL. In addition, notably, there is one negative relationship between TRU→BL, which is the opposite result to the one hypothesized. This negative relationship may be because while theoretically trust can be assumed to have a positive effect on behavioral loyalty, this result came from statistical data analysis and also is not very strong. In addition, it can be assumed that trust can be related to behavioral loyalty through other constructs, but not directly. In terms of hypothesis testing, first, H1, H2, and H3 were supported by the significant paths, RLSQ→OLSQ , RLSQ→SA, and RLSQ→TRU. H5 and H7 were also supported by the significant paths, OLSQ→SA and OLSQ→COM. In addition, H8 (SA→TRU) and H9 (TRU→COM) were accepted. However, the hypothesis H10 (SA→AL) was not supported among three paths between the construct of RQ and AL. While H15 was supported by the significant path, COM→BL, the other two paths, SA→BL and TRU→BL, were rejected. Furthermore, H16 (AL→BL) was also accepted by the significant path, AL→BL. In conclusion, 11 significant paths were identified in the structural model. Table 8/Comparing AVE and Interconstruct Correlations OLSQ RLSQ SA TRU COM AL BL 0.58 0.47 0.49 0.44 0.36 0.20 0.22 RLSQ 0.69 0.61 0.42 0.49 0.36 0.31 0.17 SA 0.70 0.65 0.82 0.50 0.40 0.28 0.27 OLSQ TRU 0.67 0.70 0.71 0.71 0.36 0.30 0.25 COM 0.60 0.60 0.63 0.60 0.75 0.29 0.37 AL 0.45 0.56 0.53 0.55 0.54 0.60 0.32 BL 0.47 0.42 0.52 0.50 0.61 0.57 0.72 Note: Diagonal elements are AVE; off-diagonal elements are correlations between constructs; above-diagonal elements are the squared correlations estimates. TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 511 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM 512 / TRANSPORTATION JOURNAL™ Discussion of the Hypotheses It was found that the impact of relational logistics service quality on operational logistics service quality is positive and very strong from the analysis (H1: Supported). While there are different studies which did not specify this link (e.g., Davis-Sramek et al. 2009), assumed a moderating effect between each of them (e.g., Zhao and Stank 2003), and assumed a co-varying relationship between them (e.g., Stank, Goldsby, and Vickery 1999), it is generally supported that relational performance is an antecedent to operational performance by Mentzer, Flint, and Hult (2001), Stank et al. (2003), and Davis-Sramek, Mentzer, and Stank (2008). From this result, it can be inferred that once a container shipping line has identified a shipper’s needs, it can better focus on the operational means of meeting them. Recently, firms have attempted to increase logistics service offering to improve their competitive positioning, which is often evaluated in terms of customer satisfaction with the services/products provided. The positive impact of logistics services on satisfying customers was consistently recognized by Innis and La Londe (1994), Daugherty, Stank, and Ellinger (1998), Mentzer, Flint, and Hult (2001), Mentzer, Myers, and Cheung (2004), Saura et al. (2008), and Bienstock et al. (2008). Moreover, together with these studies, several studies including Stank, Goldsby, and Vickery (1999), Stank et al. (2003), Zhao and Stank (2003), Davis-Sramek, Mentzer, Figure 2 The Structural Model and Significant Coefficients (Solid Lines) TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 512 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM Jang, Marlow, Mitroussi: The Effect of Logistics Service Quality \ 513 Table 9 The Results of the Hypotheses Test Standardized Regression Weight (Regression Weight) Critical ratios (t-value) Results of test RLSQ→OLSQ 0.80 (0.82) 8.51*** Supported H2 RLSQ→SA 0.29 (0.30) 2.66** Supported H3 RLSQ→TRU 0.28 (0.33) 2.72** Supported H4 RLSQ→COM 0.20 (0.20) 1.56 Not supported H5 OLSQ→SA 0.58 (0.59) 5.04*** Supported H6 OLSQ→TRU 0.10 (0.11) 0.79 Not supported H7 OLSQ→COM 0.32 (0.32) 2.42* Supported H8 SA→TRU 0.56 (0.62) 4.93*** Supported H9 TRU→COM 0.32 (0.29) 2.59** Supported H10 SA→AL 0.13 (0.13) 0.77 Not supported H11 TRU→AL 0.36 (0.35) 1.98* Supported H12 COM→AL 0.34 (0.36) 3.05** Supported Hypotheses H1 H13 SA→BL 0.01 (0.01) 0.07 Not supported H14 TRU→BL -0.08 (-0.07) - 0.44 Not Supported H15 COM→BL 0.38 (0.37) 3.34*** Supported H16 AL→BL 0.57 (0.51) 4.17*** Supported Note: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 and Stank (2008), and Davis-Sramek et al. (2009) emphasized that not only operational logistics service quality (delivering the right services/ products, with the right amount, to the right place, and at the right time), but also relational logistics service quality (how contact personnel create logistics service quality) have a positive effect on satisfaction. However, satisfaction is only one subconstruct of relationship quality. Therefore, it is difficult to judge the relationship quality comprehensively through satisfaction alone. For this reason, this research has included trust and commitment. From the analysis, it was identified that operational logistics service quality has a positive effect on satisfaction and commitment, but has no influence on trust. This indicates that it is difficult to ensure shippers’ confidence in the carriers with only operational logistics service quality. On the other hand, relational logistics service quality has a positive effect on satisfaction and trust, but has no influence on commitment. This also shows that even though shippers are satisfied and further trust carriers with a high TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 513 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM 514 / TRANSPORTATION JOURNAL™ level of relational logistics service quality, they do not commit themselves to those carriers. In conclusion, it was confirmed that H2, H3, H5, and H7 are supported from this research. In addition, the operational logistics service quality and relational logistics service quality of container shipping lines are discovered to play a different role in creating the relationship quality between shippers and carriers. Based on these results, it can be argued that satisfaction, trust, and commitment should all be considered to generate inclusive and sophisticated results. Garbarino and Johnson (1999) demonstrated the different functions of satisfaction, trust, and commitment in customer relationships. The interrelationships between them were also identified in marketing literature (e.g., Caceres and Paparoidamis 2007; Morgan and Hunt 1994). Thus, it is noteworthy to confirm these associations in maritime transport. Similar to previous studies, it was verified that shippers’ satisfaction has a positive effect on their trust and, in turn, shippers’ trust influences their commitment (H8 and H9: supported). These results also sustain the specification of relationship quality into three subconstructs. H10 through H15 dealt with the link between relationship quality and attitudinal loyalty or behavioral loyalty. First, only trust and commitment were revealed to have a positive impact on attitudinal loyalty and only commitment was discovered to have a positive effect on behavioral loyalty. In other words, shippers satisfied with container shipping lines show no attitudinal or behavioral loyalty. Once shippers can trust their carriers, they only become loyal attitudinally, but not behaviorally. In contrast, if shippers become committed to their carriers, they turn into loyal customers both attitudinally and behaviorally. From this, it can be concluded that simply satisfying shippers cannot guarantee gaining their loyalty. This emphasizes the importance of securing their trust and commitment together with their satisfaction. Furthermore, trust is only limited to shippers’ attitudinal loyalty, but it does not lead to creating behavioral loyalty. Even though extant literature reveals contradictory positions on commitment and loyalty, this study follows the stream that these two represent distinct concepts as supported by Beatty and Kahle (1988), and concludes that only commitment can result in both attitudinal and behavioral loyalty (H11, H12, and H15: supported). Finally, it was highlighted by Dick and Basu (1994) that loyalty consists of both attitudinal and behavioral aspects in which Bandyopadhyay and Martell (2007) discovered that attitudinal loyalty was positively related to behavioral loyalty. In this research, this positive relationship was also TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 514 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM Jang, Marlow, Mitroussi: The Effect of Logistics Service Quality \ 515 confirmed, and consequently, it can be concluded that by attaining attitudinal loyalty, it is possible to make shippers behaviorally loyal to container shipping lines (H16: supported). Conclusions and Implications The results of the study provide container shipping lines with a holistic understanding of the role of logistics service quality, relationship quality, and customer loyalty in the container shipping context. The findings also offer various contributions to theory and practice. First, this study contributes to the body of knowledge in relationship marketing, logistics/SCM, and maritime transport in the business-to-business context by expanding the existing studies on the relationship among logistics service quality, relationship quality, and the customer loyalty. It was pointed out that there were few studies on these relationships in maritime transport studies as compared to other studies undertaken in the logistics and supply chain research context (e.g., Daugherty, Stank, and Ellinger 1998; Davis-Sramek, Mentzer, and Stank 2008; Rauyruen and Miller 2007). Second, more complexity is added when these relationships are simultaneously explored in a holistic manner. Thus, the results of this study provide a new research framework that offers a more in-depth insight into logistics service quality, relationship quality, and customer loyalty. It should also be noted that all constructs employed in this study are conceptualized to be multidimensional and while some existing measures were used, several new measures were added from the qualitative study. Third, to the authors’ knowledge, this research specifically contributes to the maritime transport studies in that it has scrutinized the carrier-shipper relationships thoroughly focusing on customer loyalty for the first time. Previous studies on maritime transport were more likely to identify carrier selection criteria or shippers’ satisfaction or the importance they attached to service attributes (e.g., Casaca and Marlow 2005; Kent and Parker 1999). This may be attributed to the fact that companies regarded satisfaction as a customer’s future purchase intentions as argued by Drucker (2004). However, this study shows that simply satisfying customers does not indicate that firms will retain their customers, despite the importance of the critical role of satisfaction. Furthermore, this study considers relationship quality together to explore the customer loyalty phenomenon in the container shipping context. Fourth, considering the contributions to the industry, container shipping lines TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 515 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM 516 / TRANSPORTATION JOURNAL™ can utilize the results of this study to segment the shippers according to their loyalty types. In other words, understanding the loyalty relationships with logistics services helps carriers to distinguish their shippers’ segments and further decide the level of logistics services to each group. It is almost impossible to satisfy every customer or market segment, given that different shippers have different needs and desires. For that reason, it is vital to manage their logistics service capabilities strategically to each group as well as pursue stronger relationships with shippers who are more loyal to them. Despite the significant contributions mentioned above, this study has several limitations. First, there is the generalizability issue in this study since the data collected came from a limited sample within one country, and within a limited time frame. Second, as this study has the confirmatory purposes on the research model and hypotheses developed before collecting the data, further relationships between the constructs cannot be considered. Nor can the dimensions and structures of the constructs be modified or observed measures be added to. More important, customer loyalty should be investigated to anticipate the market share as supported by Daugherty, Stank, and Ellinger (1998) and Stank et al. (2003). Additionally, the moderating effect can be analyzed on the basis of other factors, including switching barriers, a firm’s characteristics, or cultural differences. TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 516 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM Jang, Marlow, Mitroussi: The Effect of Logistics Service Quality \ 517 Appendix Category Logistics service quality (LSQ) Relationship quality (RQ) Customer loyalty (CL) Construct Observation Variable (Indicator) Operational logistics service quality (OLSQ) OLSQ01: Flexible pricing policy in meeting competitor’s rates OLSQ02: Short transit time OLSQ03: Satisfactory service frequency OLSQ04: The ability to provide the correct type and quantity of equipment (e.g. container and chassis) consistently OLSQ05: Good reputation and image OLSQ06: Satisfactory terminal services OLSQ07: Cargo space availability Relational logistics service quality (RLSQ) RLSQ08: Sales personnel’s willingness to respond promptly to problems and complaints RLSQ09: Sales personnel’s knowledgeability RLSQ10: Sales personnel’s courtesy RLSQ11: Sales personnel’s ability to develop a long-term relationship RLSQ12: Sales personnel’s personal attention and effort to understand the individual situation RLSQ13: Sales personnel’s frequency of calls RLSQ14: Sales personnel’s effort to establish and respond to the needs Satisfaction (SA) SA01: Contentment of doing business with my primary liner shipping company SA02: Feeling that the decision to do business with my primary liner shipping company was a wise decision SA03: Satisfaction with the performance of my primary liner shipping company Trust (TRU) TRU04: Belief that my primary liner shipping company keeps its promises TRU05: Belief that my primary liner shipping company is sincere and trustworthy TRU06: Belief that my primary liner shipping company does not withhold certain pieces of critical information that might have affected the decision-making Commitment (COM) COM07: Preference to do business with my primary liner shipping company rather than with others COM08: Willingness to put in more effort to do business with my primary liner shipping company than others COM09: Wish to remain a customer of my primary liner shipping company as the relationship with them is enjoyable Attitudinal loyalty (AL) AL01: Thinking that it is necessity as much as desire that keeps me involved with my primary liner shipping company AL02: Feeling that I am attached emotionally to my primary liner shipping company AL03: Feeling that my primary liner shipping company deserves my loyalty to it Behavioral loyalty (BL) BL04: Willingness to continue to do business with my primary liner shipping company in the next year BL05: Intention to do more business with my primary liner shipping company, all things being equal BL06: Thinking that my primary liner shipping company is my first choice for liner shipping services Note This article is a revised version of an earlier paper presented at the 2012 International Association of Maritime Economists–IAME, Taiwan, September 6–8. TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 517 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM 518 / TRANSPORTATION JOURNAL™ References Acciaro, M. 2010. “Bundling Strategies in Global Supply Chains.” PhD thesis, Erasmus University. Anderson, J. C., and D. W. Gerbing. 1988. “Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach.” Psychological Bulletin 103 (3): 53–66. Armstrong, J. S., and T. S. Overton. 1977. “Estimating Nonresponse Bias in Mail Surveys.” Journal of Marketing Research 14 (3): 396–402. Baird, A. J. 2003. “Global Strategy in the Maritime Sector: Perspectives for the Shipping and Ports Industry.” Paper presented at the Third Meeting of the InterAmerican Committee on Port (CIP), Mérida, Mexico, September 9–13. Bandyopadhyay, S., and M. Martell. 2007. “Does Attitudinal Loyalty Influence Behavioral Loyalty? A Theoretical and Empirical Study.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 14 (1): 35–44. Beatty, S. E., and L. R. Kahle. 1988. “Alternative Hierarchies of the Attitude-Behavior Relationship: the Impact of Brand Commitment and Habit.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 16 (2): 1–10. Bennett, R., and H. Gabriel. 2001. “Reputation, Trust and Supplier Commitment: The Case of Shipping Company/Seaport Relations.” Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing 16 (6): 424–38. Bienstock, C. C., M. B. Royne, D. Sherrell, and T. F. Stafford. 2008. “An Expanded Model of Logistics Service Quality: Incorporating Logistics Information Technology.” International Journal of Production Economics 113 (1): 205–22. Bird, J., and G. Bland. 1988. “Freight Forwarders Speak: The Perception of Route Competition via Seaports in the European Communities Research Project. Part 1.” Maritime Policy and Management 15 (1): 35–55. Boles, J. S., J. T. Johnson, and J. C. J. Barksdale. 2000. “How Salespeople Build Quality Relationships: A Replication and Extension.” Journal of Business Research 48 (1): 75–81. Brooks, M. R. 1990. “Ocean Carrier Selection Criteria in a New Environment.” Logistics and Transportation Review 26 (4): 339–55. Caceres, R. C., and N. G. Paparoidamis. 2007. “Service Quality, Relationship Satisfaction, Trust, Commitment and Business-to-Business Loyalty.” European Journal of Marketing 41 (7/8): 836–67. Carbone, V., and E. Gouvernal. 2007. “Supply Chain and Supply Chain Management: Appropriate Concepts for Maritime Studies.” In Ports, Cities, and Global Supply Chains, ed. J. Wang et al., 11–26. Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing. Casaca, A. C. P., and P. B. Marlow. 2005. “The Competitiveness of Short Sea Shipping in Multimodal Logistics Supply Chains: Service Attributes.” Maritime Policy and Management 32 (4): 363–82. Chaudhuri, A., and M. B. Holbrook. 2001. “The Chain of Effects from Brand Trust and Brand Affect to Brand Performance: The Role of Brand Loyalty.” Journal of Marketing 65 (2): 81–93. TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 518 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM Jang, Marlow, Mitroussi: The Effect of Logistics Service Quality \ 519 Chen, M. F., and L. H. Wang. 2009. “The Moderating Role of Switching Barriers on Customer Loyalty in the Life Insurance Industry.” Service Industries Journal 29 (8): 1105–23. D’este, G. M., and S. Meyrick. 1992. “Carrier Selection in a RO/RO Ferry Trade Part 1. Decision Factors and Attitudes.” Maritime Policy and Management 19 (2): 115–26. Daugherty, P. J., T. P. Stank, and A. E. Ellinger. 1998. “Leveraging Logistics/Distribution Capabilities: The Effect of Logistics Service on Market Share.” Journal of Business Logistics 19 (2): 35–52. Davis, B. R., and J. T. Mentzer. 2006. “Logistics Service Driven Loyalty: An Exploratory Study.” Journal of Business Logistics 27 (2): 53–73. Davis-Sramek, B., C. Droge, J. T. Mentzer, and M. B. Myers. 2009. “Creating Commitment and Loyalty Behavior among Retailers: What Are the Roles of Service Quality and Satisfaction?” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 37 (4): 440–54. Davis-Sramek, B., J. T. Mentzer, and T. P. Stank. 2008. “Creating Consumer Durable Retailer Customer Loyalty through Order Fulfillment Service Operations.” Journal of Operations Management 26 (6): 781–97. Dick, A. S., and K. Basu. 1994. “Customer Loyalty: Toward an Integrated Conceptual Framework.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 22 (2): 99–113. Drucker, P. E. 2004. The Daily Drucker. New York: Harper and Row. Dwyer, F. R., P. H. Schurr, and S. Oh. 1987. “Developing Buyer-Seller Relationships.” Journal of Marketing 51 (2): 11–27. Evangelista, P. 2005. “Innovating Ocean Transport through Logistics and ICT.” In International Maritime Transport: Perspectives, ed. H. Leggate, J. McConville, and A. Morvillo, 191–201. London: Routledge. Fynes, B., C. Voss, and S. de Búrca. 2005. “The Impact of Supply Chain Relationship Quality on Quality Performance.” International Journal of Production Economics 96 (3): 339–54. Garbarino, E., and M. S. Johnson. 1999. “The Different Roles of Satisfaction, Trust, and Commitment in Customer Relationships.” Journal of Marketing 63 (2): 70–87. Gibson, B. J., H. L. Sink, and R. A. Mundy. 1993. “Shipper-Carrier Relationships and Carrier Selection Criteria.” Logistics and Transportation Review 29 (4): 371–82. Hennig-Thurau, T., K. P. Gwinner, and D. D. Gremler. 2002. “Understanding Relationship Marketing Outcomes.” Journal of Service Research 4 (3): 230–47. Hennig-Thurau, T., and A. Klee. 1997. “The Impact of Customer Satisfaction and Relationship Quality on Customer Retention: A Critical Reassessment and Model Development.” Psychology and Marketing 14 (8): 737–64. Howard, J. A., and J. H. Sheth. 1969. The Theory of Buyer Behaviour. New York: John Wiley and Sons. Innis, D. E., and B. J. La Londe. 1994. “Customer Service: The Key to Customer Satisfaction, Customer Loyalty, and Market Share.” Journal of Business Logistics 15 (1): 1–27. Jacoby, J., and D. B. Kyner. 1973. “Brand Loyalty vs. Repeat Purchasing Behavior.” Journal of Marketing Research 10(1): 1–9. TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 519 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM 520 / TRANSPORTATION JOURNAL™ Jones, T. O., and W. E. Sasser. 1995. “Why Satisfied Customers Defect.” Harvard Business Review 73 (6): 88–99. Kent, J. L., and R. S. Parker. 1999. “International Containership Carrier Selection Criteria: Shippers/Carriers Differences.” International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management 29 (6): 398–408. Kline, R. B. 2005. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press. Lambert, D. M., and T. C. Harrington. 1990. “Measuring Nonresponse Bias in Customer Service Mail Surveys.” Journal of Business Logistics 11 (2): 5–25. Lin, C., W. S. Chow, C. N. Madu, C. -H. Kuci, and P. P. Yu. 2005. “A Structural Equation Model of Supply Chain Quality Management and Organizational Performance.” International Journal of Production Economics 96 (3): 355–65. Liu, C. T., Y. M. Guo, and C. H. Lee. 2011. “The Effects of Relationship Quality and Switching Barriers on Customer Loyalty.” International Journal of Information Management 31 (1): 71–79. Lu, C. S. 2003a. “An Evaluation of Service Attributes in a Partnering Relationship between Maritime Firms and Shippers in Taiwan.” Transportation Journal 42 (5): 5–16. ———. 2003b. “The Impact of Carrier Service Attributes on Shipper-Carrier Partnering Relationships: A Shipper’s Perspective.” Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 39 (5): 399–415. Maignan, I., O. C. Ferrell, and G. T. M. Hult. 1999. “Corporate Citizenship: Cultural Antecedents and Business Benefits.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 27 (4): 455–69. Martin, J., and B. J. Thomas. 2001. “The Container Terminal Community.” Maritime Policy and Management 28 (3): 279–92. Matear, S., and R. Gray. 1993. “Factors Influencing Freight Service Choice for Shippers and Freight Suppliers.” International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management 23 (2): 25–35. Mentzer, J. T., D. J. Flint, and G. T. M. Hult. 2001. “Logistics Service Quality as a Segment-Customized Process.” Journal of Marketing 65 (4): 82–104. Mentzer, J. T., M. B. Myers, and M. S. Cheung. 2004. “Global Market Segmentation for Logistics Services.” Industrial Marketing Management 33 (1): 1–18. Morgan, R. M., and S. D. Hunt. 1994. “The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing.” Journal of Marketing 58 (3): 20–38. Murphy, P. R., and J. M. Daley. 2001. “Profiling International Freight Forwarders: An Update.” International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management 31 (3): 152–68. Oliver, R. L. 1999. “Whence Consumer Loyalty?” Journal of Marketing 63 (4): 33–44. Panayides, P. M., and M. So. 2005. “The Impact of Integrated Logistics Relationships on Third-Party Logistics Service Quality and Performance.” Maritime Economics and Logistics 7 (1): 36–55. Qin, S., L. Zhao, and X. Yi. 2009. “Impacts of Customer Service on Relationship Quality: An Empirical Study in China.” Managing Service Quality 19 (4): 391–409. TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 520 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM Jang, Marlow, Mitroussi: The Effect of Logistics Service Quality \ 521 Rauyruen, P., and K. E. Miller. 2007. “Relationship Quality as a Predictor of B2B Customer Loyalty.” Journal of Business Research 60 (1): 21–31. Roberts, K., S. Varki, and R. Brodie. 2003. “Measuring the Quality of Relationships in Consumer Services: An Empirical Study.” European Journal of Marketing 37 (1/2): 169–96. Sakar, G. D. 2010. “Mode Choice Decisions and the Organisational Buying Processes in Multimodal Transport: A Triangulated Approach.” PhD thesis, Cardiff University. Saura, I. G., D. S. Francés, G. B. Contrí, and M. F. Blasco. 2008. “Logistics Service Quality: A New Way to Loyalty.” Industrial Management and Data Systems 108 (5): 650–68. Schurr, P. H., and J. L. Ozanne. 1985. “Influences on Exchange Processes: Buyers’ Preconceptions of a Seller’s Trustworthiness and Bargaining Toughness.” Journal of Consumer Research 11 (4): 939–53. Stank, T. P., T. J. Goldsby, and S. K. Vickery. 1999. “Effect of Service Supplier Performance on Satisfaction and Loyalty of Store Managers in the Fast Food Industry.” Journal of Operations Management 17 (4): 429–47. Stank, T. P., T. J. Goldsby, S. K. Vickery, and K. Savitskie. 2003. “Logistics Service Performance: Estimating Its Influence on Market Share.” Journal of Business Logistics 24 (1): 27–55. Tongzon, J. 2002. “Port Choice Determinants in a Competitive Environment.” Paper presented at the Annual Conference and Meeting of the International Association of Maritime Economists-IAME, Panama, November 13–15. Vickery, S. K., C. Droge, T. P. Stank, T. J. Goldsby, and R. E. Markland. 2004. “The Performance Implications of Media Richness in a Business-to-Business Service Environment: Direct versus Indirect Effects.” Management Science 50 (8): 1106–19. Wang, T. F. 2006. “An Empirical Investigation of Liner Shipping Performance.” Paper presented at the Annual Conference and Meeting of the International Association of Maritime Economists-IAME, Melbourne, July 12–14. Zhao, M., and T. P. Stank. 2003. “Interactions between Operational and Relational Capabilities in Fast Food Service Delivery.” Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 39 (2): 161–73. TJ 52.4_05_Jang-Marlow-Mitroussi.indd 521 This content downloaded from 37.18.79.68 on Sat, 16 Mar 2024 22:13:38 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 04/10/13 8:33 AM