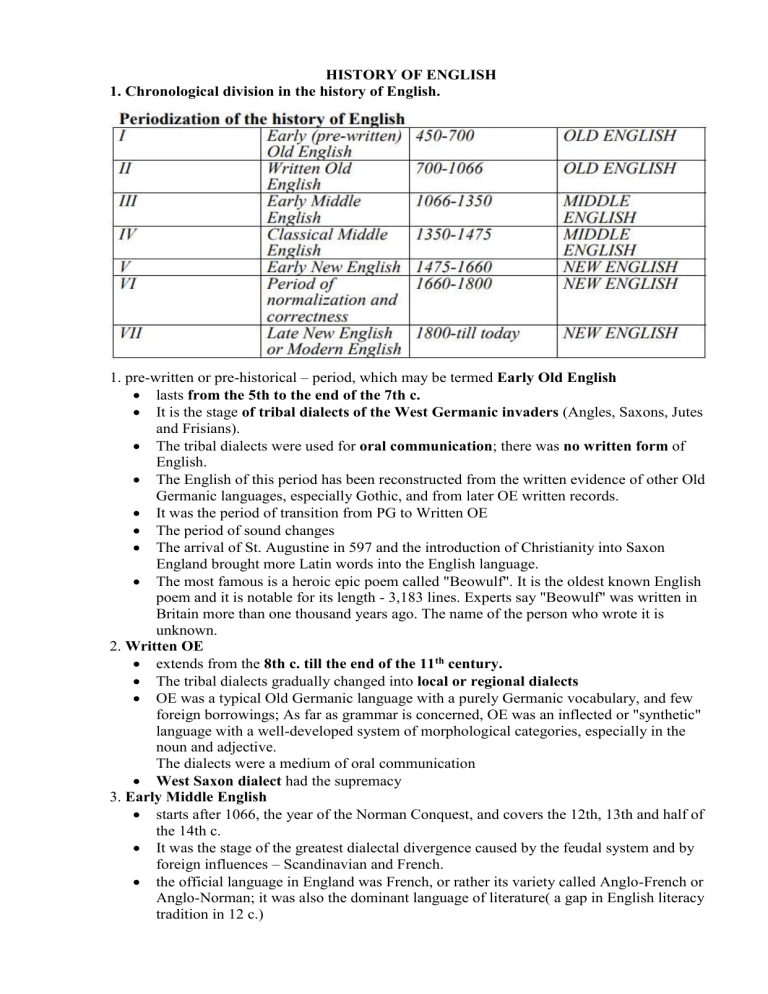

HISTORY OF ENGLISH

1. Chronological division in the history of English.

1. pre-written or pre-historical – period, which may be termed Early Old English

lasts from the 5th to the end of the 7th c.

It is the stage of tribal dialects of the West Germanic invaders (Angles, Saxons, Jutes

and Frisians).

The tribal dialects were used for oral communication; there was no written form of

English.

The English of this period has been reconstructed from the written evidence of other Old

Germanic languages, especially Gothic, and from later OE written records.

It was the period of transition from PG to Written OE

The period of sound changes

The arrival of St. Augustine in 597 and the introduction of Christianity into Saxon

England brought more Latin words into the English language.

The most famous is a heroic epic poem called "Beowulf". It is the oldest known English

poem and it is notable for its length - 3,183 lines. Experts say "Beowulf" was written in

Britain more than one thousand years ago. The name of the person who wrote it is

unknown.

2. Written OE

extends from the 8th c. till the end of the 11th century.

The tribal dialects gradually changed into local or regional dialects

OE was a typical Old Germanic language with a purely Germanic vocabulary, and few

foreign borrowings; As far as grammar is concerned, OE was an inflected or "synthetic"

language with a well-developed system of morphological categories, especially in the

noun and adjective.

The dialects were a medium of oral communication

West Saxon dialect had the supremacy

3. Early Middle English

starts after 1066, the year of the Norman Conquest, and covers the 12th, 13th and half of

the 14th c.

It was the stage of the greatest dialectal divergence caused by the feudal system and by

foreign influences – Scandinavian and French.

the official language in England was French, or rather its variety called Anglo-French or

Anglo-Norman; it was also the dominant language of literature( a gap in English literacy

tradition in 12 c.)

Towards the end of the period their literary prestige grew, as English began to displace

French in the sphere of writing, as well as in many other spheres.

Early ME was a time of great changes at all the levels of the language, especially in lexis and

grammar. English absorbed two layers of lexical borrowings: the Scandinavian element (NorthEast) and the French element (the South-East).Numerous phonetic and grammatical changes

took place in this period. Grammatical alterations were so drastic that by the end of the period

they had transformed English from a highly inflected language into a mainly analytical one.

Therefore, H. Sweet called Middle English the period of “leveled endings”.

4. Late or Classical Middle English

from the later 14th c. till the end of the 15th century – embraces the age of Chaucer,

It was the time of the restoration of English to the position of the state and literary

language and the time of literary flourishing.

The main dialect used in writing and literature was the mixed dialect of London.

The written forms developed and improved

The growth of English vocabulary

The phonetic and grammatical structure had undergone fundamental changes. Most of the

inflections in the nominal system – in nouns, adjectives, pronouns – had fallen together.

H. Sweet called Middle English the period of “levelled endings”.

5. Early New English

lasted from the introduction of printing and embraced age of Shakespeare. This period

started in 1475 and ended in 1660.

The first printed book in English was published by William Caxton in 1475.

This period is a sort of transition between two literary epochs - the age of Chaucer and

the age of Shakespeare (also known as the Literary Renaissance)

In this period the country became economically and politically unified; the changes in the

political and social structure, the progress of culture, education, and literature led to

linguistic unity. Thus, the national English language was developed.

Early New English was a period of great changes at all levels, especially lexical and

phonetic: The the growth of the vocabulary, the vowel system was greatly

transformed,The loss of most inflectional endings in the 15th c. justifies the definition

“period of lost endings” given by H. Sweet to the NE period

6. “the age of normalization and correctness”( neo-classical age)

lasts from the mid-17th c. to the end of the 18th c

The norms of literary language were fixed as rules( received standarts) Numerous

dictionaries and grammar-books were published and spread through education and

writing.

The 18th c. is called the period of “fixing the pronunciation”. The great vowel shift was

over and pronunciation was stabilized

Word usage and grammatical constructions were also stabilized.

The formation of new verbal grammatical categories was completed.

Syntactical structures were perfected and standardized.

during this period the English language extended its area far beyond the borders of the

British Isles, first of all to North Americ

7. Late New English or Modern English

19th and 20th c

The main difference between Early Modern English and Late Modern English is

vocabulary. Late Modern English has many more words, arising from two principal

factors: firstly, the Industrial Revolution and technology created a need for new words;

secondly, the British Empire at its height covered one quarter of the earth's surface, and

the English language adopted foreign words from many countries.

By the 19th c. English had acquired all the properties of a national language.

The classical language of literature was strictly distinguished from the local dialects.

The dialects were used only in oral communication.

The “best” form of English, the Received Standard, was spread

Some geographical varieties of English are now recognized as independent variants of

the language.

In the 19th and 20th c. the English vocabulary has grown due to the rapid progress of

technology, science, trade and culture.

an English speaker of the 21st century uses a form of language different from that used

by the characters of Dickens or Thackeray one hundred and eighty years ago.

It was the final stage of development, or as a cross-section representing Present-day

English.

There have been certain linguistic changes in phonetics and grammar: some

pronunciations and forms have become old-fashioned, while other forms have been

accepted as common usage.

2. Evolution of the nominal parts of speech from OE to NE.

When speaking about the nominal parts of speech, that is noun, adjective, pronoun and numeral,

we should say that the tendency of their development was simplification. It means that the

paradigms of these parts of speech were simplified. They lost some of the categories and those

which remained consist of fewer members.

The Noun had the following categories in OE:

Number – Singular and Plural

Case – Nominative (Nom), Genitive (Gen), Dative (Dat), Accusative (Acc).

Gender – Masculine (M), Feminine (F), Neuter (N):

o In OE the nouns started to grouped into genders according to the suffix:

-þu (F) – e.g. lenζþu (length);

-ere (M) – e.g. fiscere (fisher).

Old English nouns are divided as either strong or weak.

OE was a synthetic language. In building grammatical forms OE employed grammatical endings,

sound interchanges in the root, grammatical prefixes and suppletive forms.

The parts of speech in OE were the following: the noun, the adjective, the pronoun, the

numeral (nominal parts of speech), the verb, the adverb, the preposition, the conjunction, and the

interjection.

Grammatical categories are usually subdivided into nominal categories, found in nominal

parts of speech, and verbal categories, found chiefly in the finite verb. There were 5 nominal

categories in OE: number, case, gender, degrees of comparison and the category of

definiteness/indefiniteness.

The most remarkable feature of OE nouns was their system of declensions, the general number

of which exceeded twenty-five. The system of noun declensions was a sort of morphological

classification based on a number of distinctions: the stem-suffix, the gender of nouns, the

phonetic structure of the word, phonetic changes in the final syllables. According to the

traditional view, there were two main declensions – strong and weak – differing in the final

sound of the stem. The strong declension, or vowel declension, included nouns with vocalic

stems (ending in [-a-, -o-, -u-, -i-:]) and the weak, or consonant, declension included nouns with

[-n-], [-r-] and [-s-] stems. In rare cases the new form was constructed by adding the ending

directly to the root (root-stem declension). There were also minor types.

There are only two grammatical categories in the declension of nouns against three in Old

English: number and case, the category of gender having been lost at the beginning of the Middle

English period.

There are two number forms in Middle English: singular and plural.

The number of cases in Middle English is reduced as compared to Old English. There are only

two cases in Middle English: Common and Genitive, the Old English Nominative, Accusative

and Dative case having fused into one case – the Common case at the beginning of Middle

English.

In Old English we could speak of many types of consonant and vowel declensions, the a-, -n, and

root-stem being principal among them. In Middle English we observe only these three

declensions: a-stem, n-stem, root-stem. In New English we do not find different declensions, as

the overwhelming majority of nouns is declined in accordance with the original a-stem

declension masculine, the endings of the plural form –es and the Possessive –s being traced to

the endings of the original a-stem declension masculine

Thus, in ME the distinction between the OE strong and weak declension was lost. Only two

numerous groups of nouns existed in ME, distinguished mainly by their plural forms: 1) the

former a-declension which had absorved the lesser types, 2) the n-declension, which consisted of

former feminine nouns (the weak declension).

All modern irregular noun forms can be subdivided into several groups according to their origin:

1. nouns going back to the original a-stem declension, neuter gender, which had no ending in the

nominative and accusative plural even in Old English, such as: sheep – sheep (OE scēap – scēap)

2. some nouns of the n-stem declension preserving their plural form, such as: ox – oxen (OE oxa

– oxan)

c) the original s-stem declension word child – children (OE cild – cildru)

d) remnants of the original root-stem declension, such as: foot – feet (OE fōt – fēt)

5.“foreign plurals” – words borrowed in early New English from Latin. These words borrowed

were borrowed by learned people from scientific books who alone used them, trying to preserve

their original form and not attempting to adapt them to their native language. Among such words

are: Datum – data, automaton – automata, axis – axes, etc.

The adjective in OE could change for number, gender and case. Like nouns, adjectives had three

genders and two numbers. The category of case in adjectives differed from that of nouns: in

addition to the four cases(Nom, Genet, Dative,Acc) of nouns they had one more case, Instr.

Adjectives can be declined either strong/weak.

The vowel declension comprised 4 principle paradigms: a-stem, o-stem, u-stem, i-stem The

consonants decl-n comprised nouns with the stem originally ending in –n, -r, - s and some other

consonants.

Most OE adjectives distinguished between three degrees of comparison: positive, comparative

and superlative. The regular means used to form the comparative and the superlative from the

positive were the suffixes –ra and –est/-ost.

In the course of the ME period the adjective underwent greater simplifying changes than any

other part of speech. It lost all its grammatical categories with the exception of the degrees of

comparison.

By the end of the OE period the agreement of the adjective with the noun had become looser and

in the course of Early ME it was practically lost.

The first category to disappear was gender, which ceased to be distinguished by the adjective in

the 11 c.

The number of cases shown in the adjective paradigm was reduced: the Instr. case had fused with

the Dat. by the end of OE; distinction of other cases in Early ME was unsteady, as many variant

forms of different cases, which arose in Early ME, coincided. In the 13th c. case could be shown

only by some variable adjective endings in the

strong declension (but not by the weak forms); towards the end of the century all case

distinctions were lost.

The strong and weak forms of adjectives were often confused in Early ME texts. The use of a

strong form after a demonstrative pronoun was not uncommon, though according to the existing

rules, this position belonged to the weak form.

In the 14th c. the difference between the strong and weak form is sometimes shown in the

singular with the help of the ending –e.

Number was certainly the most stable nominal category in all the periods. In the 14th c. plural

forms were sometimes contrasted to the singular forms with the help of the ending -e in the

strong declension. In the 13th and particularly 14th c. there appeared a new plural ending -s.

The degrees of comparison are the only set of forms which the adjective has preserved through

all historical periods. However, the means employed to build up the forms of the degrees of

comparison have considerably altered. It should be noted, however, that out of three principal

means of forming degrees of comparison that existed in old English: suffixation, vowel

interchange and suppletive forms, there remained as a productive means only one: suffixation,

the rest of the means seen only in isolated forms. In ME the fourth way of making degrees of

comparison appeared – by means of using more and most in the comparative and superlative

degrees: interesting – more interesting – most interesting.

Thus, the most important innovation in the adjective system in the ME period was the growth of

analytical forms of the degrees of comparison.

In ME, when the phrases with ME more and most became more and more common, they were

used with all kinds of adjectives, regardless of the number of syllables and were even preferred

with mono- and disyllabic words.

OE pronouns fell roughly under the same main classes as modern pro-nouns; personal,

demonstrative, interrogative and indefinite. OE personal pronouns had three persons, three

numbers in the 1st and 2nd p. (two numbers — in the 3rd) and three genders in the 3rd p. In OE,

while nouns consistently distinguished between four cases, personal pronouns began to lose

some of their case distinctions: the forms of the Dat. case of the pronouns of the 1st and 2nd p.

were frequently used instead of the Acc.

There were two demonstrative pronouns in OE: the prototype of NE that, which distinguished

three genders in the sg and had one form for all the genders in the pl. and the prototype of this

with the same subdivisions: They were declined like adjectives according to a five-case system:

Nom., Gen., Dat., Acc, and Instr. (the latter having a special form)

Demonstrative pronouns are of special importance for a student of OE for they were frequently

used as noun determiners and through agreement with the noun, indicated its number, gender and

case

Interrogative pronouns —had a four-case paradigm (NE who, what). The Instr. case of hwæt was

used as a separate interrogative word hwӯ (NE why). Some interrogative pronouns were used as

adjective pronouns, e. g. hwelc, hwæper.

Indefinite pronouns were a numerous class embracing several simple pronouns and a large

number of compounds: ān and its derivative ǣniʒ (NE me, any);

The four-case system that existed in OE gave way to a two-case system. The genitive case as a

form of a personal pronoun disappeared and merged with the possessive pronouns, retaining only

its ability to express possessive meaning in the function of an attribute. The dative and

accusative cases merged in one objective case.

As a grammatical phenomenon gender disappeared already in Middle English, the pronouns he

and she referring only to animate notions and it – to inanimate.

The three number system that existed in Early Old English (singular, dual, plural) was

substituted by a two number system already in Late Old English

The new fem. pronoun, Late ME she, is believed to have developed from the OE demonstrative

pronoun of the fem. gender – sēo (OE sē, sēo, þæt, NE that).

In the course of ME another important lexical replacement took place: the OE pronoun of the 3rd

p. pl. hīe was replaced by the Scand. loan-word they [ ei].

Demonstrative pronouns were adjective-pronouns; like other adjectives, in OE they agreed with

the noun in case, number and gender and had a well-developed morphological paradigm. The OE

forms of the demonstrative pronoun (or definite article) sē, sēo were changed into þe, þēo on the

analogy of the forms derived from the root þ-. In Early ME forms like and þe, þēo, þat

functioned both as demonstrative pronoun and as article.

The other classes of OE pronouns were subjected to the same simplifying changes as all nominal

parts of speech.

The OE interrogative pronouns hwā, hwæt > who, what have three cases in ME:

Nom. Gen. Obj. The form of the OE Instr. case hwy developed into an adverb why ‘why’.

Most indefinite pronouns of the OE period simplified their morphological structure and some

pronouns fell out of use. For instance, man died out as an indefinite pronoun; Eventually new

types of compound indefinite pronouns came into use – with the component -thing, -body, -one,

etc; in NE they developed a two-case paradigm like nouns: the Comm. and the Poss. or Gen.

case: anybody – anybody's.

Reflexive pronouns appeared as a result of combining the form of the objective case of personal

pronouns with the form self

The first elements of the category of the article appeared already in Old English, when the

meaning of the demonstrative pronoun was weakened, and it approach the status of an article in

such phrases as:

Sē mann (the mann), sēo sǽ (the sea), þæt lond (the land)

However, we may not speak of any category if it is not represented by an opposition of at least

two units. Such opposition arose only in Middle English, when the indefinite article an appeared.

The form of the definite article the can be traced back to the old English demonstrative

pronoun sē (that, masculine, singular), which in the course of history came to be used on

analogy with the forms of the same pronoun having the initial consonant [θ]and began to be used

with all nouns, irrespective of their gender or number.

The indefinite article developed from the Old English numeral ān. In Middle English ān split

into two words: the definite pronoun an, losing a separate stress and undergoing reduction of its

vowel, and the numeral one, remaining stressed as only other notional word. Later the indefinite

pronoun an grew into the indefinite article a/an, and together with the definite article the formed

a new grammatical category – the category of determination, or the category of article.

Numerals from 1 to 3 were declined. Numerals from 4 to 19 were usually invariable, if used as

attributes to a noun, but they were declined if used without a noun. Numerals denoting tens had

their Gen. in –es or in –a, -ra, their Dat. in –um.

1 – ān (was declined as a strong adjective)

2 – twe3en (M), tū, twā (N), twā (F)

3 – þrīe, þrī, þrý (M), þrīo, þrēo (N), þrīo, þrēo (F).

4 – fēower

5 – fīf

6 – siex, six, syx

7 – seofon, siofon, syofn

8 – eahta

9 – ni3on

10 – tīen, týn, tēn

11 – endlefan

12 – twelf

Numerals from 13 to 19 were derived from compounding of the first 9 numerals and the

numeral tīen (týn, tēn) - 10, e.g. fiftīen – 15.

Numbers consisting of tens (from 20 to 60) were composed by the proper numeral (from 2 to 6)

and suffix –ti(3), e.g. twenti3 - 20. From 70 to 100 the names of the numerals had such part

as hund – 100, e.g. hundsiofonti3 – 70. Numerals from 100 to 900 had this part as their last

component: tū hund – 200. 1000 was called þūsend. Numbers consisting of tens and units were

denoted in the following way: twā and twenti3 – 22.

Numbers ān – 1, twē3en – 2 and þrīe – 3 had the special ordinals: forma, fyresta; ōþer, æfterra;

þridda, þirda. The rest of the ordinal numerals were composed by adding –þa to the root ending

in the vowel or voiced consonant and by –ta to the root ending in voiceless consonant,

e.g. twelfta – 12-й, seofoþa – 7- й (-n before –þa was lost).

3. Development of the national literary English language.

The formation of the national literary English language covers the Early NE period (c.1475—

1660). There were at least two major external factors which favoured the rise of the national

language and the literary standards: the unification of the country and the progress of culture.

Other historical events, such as increased foreign contacts, affected the language in a less general

way: they influenced the growth of the vocabulary.

Introduction of Printing

The invention of printing had the most immediate effect on the development of the language, its

written form in particular. "Artificial writing", as printing was then called, was invented in

Germany in 1438 (by Johann Gutenberg); the first printer of English books was William Caxton.

Written Standard

Its growth and recognition as the correct or "prestige" form of the language of writing had been

brought about by the factors: the economic and political unification of the country, the progress

of culture and education, the flourishing of literature.

Early New English (15th – beginning of the 18th century) – the establishment of the literary

norm. The language that was used in England at that time is reflected in the famous translation of

the Bible called the King James Bible (published in 1611). Although the language of the Bible is

Early Modern English, the author tried to use a more solemn and grand style and more archaic

expressions.

A great influence was also connected with the magazine by Joseph Addison and Richard Steele

called The Spectator (1711 – 1714), the authors of which discussed various questions of the

language, including its syntax and the use of words.

Growth of the Spoken Standard. The Written Standard had probably been fixed and

recognised by the beginning of the 17th c. The next stage in the growth of the national literary

language was the development of the Spoken Standard. The dating of this event appears to be

more problematic. It seems obvious that in the 18th c. the speech of educated people differed

from that of common, uneducated people — in pronunciation, in the choice of words and in

grammatical construction. The number of educated people was growing and their way of

speaking was regarded as correct.

Thus by the end of the 18th c. the formation of the national literary English language may be

regarded as completed, for now it possessed both a Written and a Spoken Standard.

The formation of the national literary English language covers the Early NE period (c. 1475—

1660).

There were at least two major external factors which favoured the rise of the national language

and the literary standards: the unification of the country and the progress of culture.

The term "national" language embraces allthe varieties ofthe language used by thenation

including dialects; the ''national literary language"applies only to recognized standard forms of

the language, both written and spoken.

The end of the Middle English period and the beginning of New English is marked by the

following events in the life of the English people:

1) The end of the war between the White and the Red Rose (1485) and the establishment of an

absolute monarchy on the British soil with Henry Tudor as the first absolute monarch – the

political expression of the English nation.

The War of the Roses (1455 – 1485) was the most important event of the 15th century which

marked the decay of feudalism and the birth of a new social order. It signified the rise of an

absolute monarchy in England and a political centralisation, and consequently a linguistic

centralisation leading to a predominance of the national language over local dialects.

2) The introduction of printing (1477) by William Caxton (1422— 1490).

Printing was invented in Germany by Johann Gutenberg in 1438. It quickly spread to other

countries and England was among them. The first English printing office was founded in 1476

by William Caxton.The appearance of a considerable number of printed books contributed to the

normalisation of spelling and grammar forms fostering the choice of a single variant over others.

Caxton, a native of Kent, acquired the London dialect and made a conscious choice from among

competing variants.

Since that time – the end of the 15th century the English language began its development as the

language of the English nation, whereas up to that time, beginning with the Germanic conquest

of Britain in the 5th century and up to the 15thcentury, the English language was no more than a

conglomerate of dialects, first tribal and then local. Indeed, a notable feature of the Middle

English period is the dialectical variety that finds expression in the written documents. It was

only late in the 14thcentury that the London dialect, itself a mixture of the southern and southeastern dialects, began to emerge as the dominant type.

In New English there emerged one nation and one national language. But the English literary

norm was formed only at the end of the 17th century, when the first scientific English

dictionaries and the first scientific English grammar appeared. In the 17th and 18th centuries there

appeared a great number of grammar books whose authors tried to stabilise the use of the

language.

The grammars and dictionaries of the 18th c. succeeded in formulating the rules of usage, partly

from observation but largely from the "doctrine of correctness", and laid them down as norms to

be taught as patterns of correct English. Codification of norms of usage by means of conscious

effort on the part of man helped in standardising the language and in fixing its written and

spoken standards.

The next stage in the growth of the national literary language was the development of the

Spoken Standard. The dating of this event appears to be problematic.

Naturally, we possess no direct evidence of the existence of oral norms, since all evidence comes

from written sources. Nevertheless, valuable information has been found in private letters as

compared to more official papers, in the speech of various characters in 17th and 18th c. drama,

and in direct references to different types of oral speech made by contemporaries.

It seems obvious that in the 18th c. the speech of educated people differed from that of common,

uneducated people — in pronunciation, in the choice of words and in grammatical construction.

The number of educated people was growing and their way of speaking was regarded as correct.

Compositions on language gave diverse recommendations aimed at improving the forms of

written and oral discourse. Some authors advised people to model their speech on Latin patterns;

others banned borrowing mannerisms and vulgar pronunciation. These recommendations could

only be made if their authors were — or considered themselves to be — in a position to

distinguish between different forms of speech and label them as “good” or “bad”. Indirectly they

testify to the existence of recognised norms of educated spoken English.

The earliest feasible date for the emergence of the Spoken Standard suggested by historians

is the late 17th c. Some authorities refer it to the end of the normalisation period, that is

about a hundred years later — the end of the 18th c.The latter date seems to be more realistic,

as by that time current usage had been subjected to conscious regulation and had become more

uniform. The rules formulated in the prescriptive grammars and dictionaries must have had their

effect not only on the written but also on the spoken forms of the language.

The concept of Spoken Standard does not imply absolute uniformity of speech throughout the

speech community — a uniformity which, in fact, can never be achieved; it merely implies a

more or less uniform type of speech used by educated people and taught as “correct English” at

schools and universities. The spoken forms of the language, even when standardised, were never

as stable and fixed as the Written Standard. Oral speech changed under the influence of sub-

standard forms of the language, more easily than the written forms. Many new features coming

from professional jargons, lower social dialects or local dialects first entered the Spoken

Standard, and through its medium passed into the language of writing. The Written Standard, in

its turn, tended to restrict the colloquial innovations labelling them as vulgar and incorrect and

was enriched by elements coming from various functional and literary styles, e.g. poetry,

scientific style, official documents. Between all these conflicting tendencies the national literary

language, both in its written and spoken forms, continued to change during the entire New

English period.

The geographical and social origins of the Spoken Standard were in the main the same as those

of the Written Standard some two-hundred years before: the tongue of London and the

Universities, which in the turbulent 17th c. — the age of the English Revolution, further

economic progress and geographical expansion — had assimilated many new features from a

variety of sources. Intermixture of people belonging to different social groups was reflected in

speech, though the rate of changes was slowed down when the norms of usage had been fixed.

The nourishing of literature enriched the language and at the same time had a stabilising effect

on linguistic change.

Thus by the end of the 18th c. the formation of the national literary English language may

be regarded as completed, for now it possessed both a Written and a Spoken Standard.

4. Evolution of the sound system in ME and NE.

Sound changes, particularly vowel changes, took place in Eng¬lish at every period of history.

The development of vowels in Early OE consisted of the modifica¬tion of separate vowels, and

also of the modification of entire sets of vowels. It should be borne in mind that the mechanism

of all phonetic changes strictly conforms with the general pattern (see § 26). The change begins

with growing variation in pronunciation, which manifests itself in the appearance of numerous

allophones: after the stage of increased variation, some allophones prevail over the others and a

replacement lakes place. It may result in the splitting of phonemes and their numer¬ical growth,

which fills in the "empty boxes" of the system or introduces new distinctive features. It may also

lead to the merging of old pho¬nemes, as their new prevailing allophones can fall together. Most

fre¬quently the change will involve both types of replacement, splitting and merging, so that we

have to deal both with the rise of new phonemes and with the redistribution of new allophones

among the existing pho¬nemes. For the sake of brevity, the description of most changes below is

restricted to the initial and final stages.

The sound changes are grouped into two main stages: Early ME changes, which show the

transition from Written OE to Late ME — the age of literary flourishing or “the age of Chaucer”

— and Early NE changes, which show the transition from ME to later NE — the language of

the 18th and 19th c.

The Great vowel shift was a series of consistent changes of long vowels accounting for many

features of the ME vowel system and also of the modern spelling system. During this period all

the long vowels became closer or were diphthongised. Some of the vowels occupied the place of

the next vowel; [e:] > [i:], [o:] > [u:], while the latter changed to [au].

The regular qualitative changes of all the long vowels between the 14th and the 17th centuries are

known in the history of the English language as the Great vowel shift.

In ME a great change affected the entire system of vowel phonemes. OE had both short and long

vowel phonemes, which were absolutely independent and could occur in any phonetic

environment. In the 10th-12th c. quantity of vowels becomes dependent on their environment: in

some phonetic environment only short vowels can appear, while in other – only long due to a

number of changes:

shortening: Long vowels occurring before two consonants are shortened; though they remain

long before “lengthening” consonant groups “ld, nd, md” and before clusters belonging to the

following syllable. They are also shortened before one consonant in some three-syllable words:

lengthening: Short vowels were lengthened in open syllables and affected short vowels “a, e, o”.

The vowels “i, u” remained unaffected though sometimes were also lengthened in open syllables,

“i” became “ē”, “u” – “ō”:

monophthongization of OE diphthongs: All OE diphthongs became monophthongs in ME:

rise of new diphthongs: New diphthongs arise in ME different from the OE ones and originated

from groups consisting of a vowel and either a palatal or velar fricative:

leveling of unstressed vowels: All unstressed vowels were weakened and reduced to a neutral

vowel which was denoted by the letter “e”:

Vowels in the unstressed position already reduced in Middle English to the vowel of the [a] type

are dropped in New English if they are found in the endings of words. The vowel in the endings

is sometimes preserved — mainly for phonetic reason:

wanted, dresses — without the intermediate vowel it would be very difficult to pronounce the

endings of such words.

Among many cases of quantitative changes of vowels in New English one should pay particular

attention to the lengthening of the vowel, when it was followed by the consonant [r]. Short

vow¬els followed by the consonant [r] became long after the disap¬pearance of the given

consonant at the end of the word or before another consonant. When the consonant [r] stood after

the vowels [e], [i], [u], the resulting vowel was different from the initial vowel not only in

quantity but also in quality.

The regular qualitative changes of all the long vowels between the 14th and the 17th centuries

are known in the history of the English language as the Great vowel shift. The Great Vowel

Shift. Due to this change the vowels became more narrow and more front.

Two short monophthongs changed their quality in NE (17th c.), the monophthong [a] becoming

[æ] and the monophthong [u] becoming [˄]

Changes of two diphthongs: [ai] > [ei], [au] > [o:].

Lengthening of vowels before [r] – due to the vocalization of consonants.

In the history of the English language the consonants were far more stable than the vowels. A

large number of consonants have remained unchanged since the OE period.

One of the most important consonant changes in the history of English was the appearance of

fricative consonant [∫] and affricates [t∫] and [dз], lacking in the OE period.

During the ME period the consonants lost their quantitative distinctions, as the long or double

consonants disappeared. The number of consonant phonemes was reduced and one of their

principal phonemic distinctive feature – opposition through quantity – was lost.

Some consonant clusters were simplified. One of the consonants, usually the first, was dropped.

E.g. kn> n, gn >n, hw> w.

Appearance of a new consonant in the system of English phonemes — [Ʒ] and the development

of the consonants [d3] and [tʃ] from palatal consonants.

Thus Middle English [sj], [zj], [tj], [dj] gave in New English the sounds [ʃ], [Ʒ], [tʃ], [dƷ].

Certain consonants disappeared at the end of the word or before another consonant, the most

important change of the kind affecting the consonant [r]

The fricative consonants [s], [Ɵ] and [f] were voiced after unstressed vowels or in words having

no sentence stress — the so-called "Verner's Law in New English"

5. The role of the foreign element at different stages of the English language development.

Native Old English words can be subdivided into a number of etymological layers from different

historical periods. The three main layers in the native OE words are:

a) common Indo-European words; names of some natural phenomena, plants and animals,

agricultural terms, names of parts of the human body, terms of kinship,

b) common Germanic words - connected with nature, with the sea and everyday life.

c) specifically OE words- layer of native words which do not occur in other Germanic or nonGermanic languages.

Although borrowed words constituted only a small portion of the OE vocabulary — all in all

about six hundred words. OE borrowings come from two sources: Celtic and Latin.

Abundant borrowing from Celtic is to be found only in place-names.

The role of the Latin language in Medieval Britain is clearly manifest; it was determined by such

historical events as the Roman occupation of Britain, the influence of the Roman civilisation and

the introduction of Christianity.

Early OE borrowings from Latin indicate the new things and con¬cepts which the Teutons had

learnt from the Romans; as seen from the examples below they pertain to war, trade, agriculture,

building and home life.

Units of measurement and containers were adopted with their Lat¬in names

Christianity in the late 6th c. and lasted to the end of OE.

Numerous Latin words which found their way into the English lan¬guage during these five

hundred years clearly fall into two main groups:

(1) words pertaining to religion, (2) words connected with learning. The rest are miscellaneous

words denoting various objects and concepts which the English learned from Latin books and

from closer acquaint¬ance with Roman culture.

The Latin impact on the OE vocabulary was not restricted to borrowing of words. There were

also other aspects of influence. The most important of them is the appearance of the so-called

"translation-loans" ─ words and phrases created on the pattern of Latin words as their literal

translations.

As mentioned before, the presence of the Scandinavians in the English population is indicated by

a large number of place-names in the northern and eastern areas

The fusion of the English and of the Scandinavian settlers progressed rapidly; in many districts

people became bilingual, which was an easy accomplishment since many of the commonest

words in the two OG languages were very much alike.

The total number of Scandinavian borrowings in English is estimated at about 900 words; about

700 of them belong to Standard English.

It is difficult to define the semantic spheres of Scandinavian borrowings: they mostly pertain to

everyday life and do not differ from native words. Only the earliest loan-words deal with

military and legal matters and reflect the relations of the people during the Danish raids and

Danish rule.

Vocabulary changes due to Scandinavian influence proceeded in different ways: a Scandinavian

word could enter the language as an innovation, without replacing any other lexical item;

sometimes the Scandinavian parallel modified the meaning of the native word without being

borrowed.

Since both languages, O Scand and OE, were closely related, Scandinavian words were very

much like native words. Therefore, assimilation of loan-words was easy. The only criteria that

can be applied are some phonetic features of borrowed words: the consonant cluster [sk] is a

frequent mark of Scandinavian loan-words, [sk] does not occur in native words, as OE [sk] had

been palatalised and modified to [∫]:

The effect of these successive and overlapping waves was seen first and foremost in a large

number of lexical borrowings in ME. At the initial stages of penetration French words were

restricted to some varieties of English: the speech of the aristocracy at the king’s court; the

speech of the middle class, who came into contact both with the rulers and with the ruled; the

speech of educated people and the population of South-Eastern towns. On the whole, prior to the

13th c. no more than one thousand words entered the English language, whereas by 1400 their

number had risen to 10,000 (75% of them are still in common use).

To this day nearly all the words relating to the government and administration of the country are

French by origin

the feudal system and words indicating titles and ranks of the nobility:

The host of military terms

A still greater number of words belong to the domain of law and jurisdiction,

A large number of French words pertain to the Church and religion,

From the loan-words referring to house, furniture and architecture

Some words are connected with art:

Another group includes names of garments:

Many French loan-words belong to the domain of entertainment,

We can also single out words relating to different aspects of the life of the upper classes and of

the town life: forms of address); names of some meals and dishes.

The extraordinary surge of interest in the classics in the age of the Renaissance opened the gates

to a new wave of borrowings from Latin and — to a lesser extent — from Greek

Some borrowings have a more specialised meaning and belong to scientific terminology

distinct semantic group of Greek loan-words pertains to theatre, literature and rhetoric

The vast body of international terms continued to grow in the 18th— 19th c. A new impetus for

their creation was given by the great technical progress of the 20th c, which is reflected in

hundreds of newly coined terms or Latin and Greek words applied in new meanings,

The foreign influence on the English vocabulary in the age of the Renaissance and in the

succeeding centuries was not restricted to Latin and Greek. The influx of French words

continued and reached new peaks in the late 15th and in the late 17th c.

French borrowings of the later periods mainly pertain to diplomatic relations, social life, art and

fashions.

Next to French, Latin and Scandinavian, English owes the greatest number of foreign words to

Italian, though many of them, like Latin loan-words, entered the English language through

French. A few early borrowings pertain to commercial and military affairs while the vast

majority of words are related to art, music and literature, which is a natural consequence of the

fact that Italy was the birthplace of the Renaissance movement and of the revival of interest in

art.

Borrowings from Spanish came as a result of contacts with Spain in the military, commercial and

political fields, due to the rivalry of England and Spain in foreign trade and colonial expansion.

Dutch made abundant contribution to English, particularly in the 15th and 16th c, when

commercial relations between England and the Netherlands were at their peak. Dutch artisans

came to England to practise their trade, and sell their goods.

Loan-words from German reflect the scientific and cultural achievements of Germany at

different dates of the New period. Mineralogical terms are connected with the employment of

German specialists in the English mining industry,

The advance of philosophy in the 18th and 19th c. accounts for philosophical terms

The earliest Russian loan-words entered the English language as far back as the 16th c, when the

English trade company (the Moskovy Company) established the first trade relations with Russia.

English borrowings adopted from the 16th till the 19th c. indicate articles of trade and specific

features of life in Russia, observed by the English:

The loan-words adopted after 1917 reflect the new social relations and political institutions in the

USSR:

In the recent decades many technical terms came from Russian, indicating the achievements in

different branches of science

THEORETICAL PHONETICS

6. The English consonants and vowels as units of the phonological system. Their

articulatory transitions in speech.

The branch of phonetics that studies the way in which the air is set in motion, the movements of

the speech organs and the coordination of these movements in the production of single sounds

and trains of sounds is called articulatory phonetics. Articulatory phonetics is concerned with the

way speech sounds are produced by the organs of speech, in other words the mechanisms of

speech production.

There are two major classes of sounds traditionally distinguished in any language - consonants

and vowels. The opposition "vowels vs. consonants" is a linguistic universal. The distinction is

based mainly on auditory effect. Consonants are known to have voice and noise combined, while

vowels are sounds consisting of voice only. From the articulatory point of view the difference is

due to the work of speech organs. In case of vowels no obstruction is made, so on the perception

level their integral characteristic is tone, not noise.

Russian phoneticians classify consonants according to the following principles: i) degree of

noise; ii) place of articulation; iii) manner of articulation; iv) position of the soft palate; v)

force of articulation.

Another point of view is shared by a group of Russian phoneticians. They suggest that the first

and basic principle of classification should be the degree of noise. Such consideration leads to

dividing English consonants into two general kinds: a) noise consonants; b) sonorants.

The term "degree of noise" belongs to auditory level of analysis. But there is an intrinsic

connection between articulatory and auditory aspects of describing speech sounds. In this case

the term of auditory aspect defines the characteristic more adequately.

There are no sonorants in the classifications suggested by British and American scholars. Daniel

Jones and Henry A. Gleason, for example, give separate groups of nasals [m, n, η], the lateral [1]

and semi-vowels, or glides [w, r, j (y)]. Bernard Bloch and George Trager besides nasals and

lateral give trilled [r]. According to Russian phoneticians sonorants are considered to be

consonants from articulatory, acoustic and phonological point of view.

(II) The place of articulation. This principle of consonant classification is rather universal. The

only difference is that V.A. Vassilyev, G.P. Torsuev, O.I. Dikushina, A.C. Gimson give more

detailed and precise enumerations of active organs of speech than H.A. Gleason, B. Bloch, G.

Trager and others. There is, however, controversy about terming the active organs of speech.

Thus, Russian phoneticians divide the tongue into the following parts: (1) front with the tip, (2)

middle, and (3) back. Following L.V. Shcherba's terminology the front part of the tongue is

subdivided into: (a) apical, (b) dorsal, (c) cacuminal and (d) retroflexed according to the position

of the tip and the blade of the tongue in relation to the teeth ridge. А.С. Gimson's terms differ

from those used by Russian phoneticians: apical is equivalent to forelingual; frontal is equivalent

to mediolingual; dorsum is the whole upper area of the tongue. H.A. Gleason's terms in respect

to the bulk of the tongue are: apex - the part of the tongue that lies at rest opposite the alveoli;

front - the part of the tongue that lies at rest opposite the fore part of the palate; back, or dorsum the part of the tongue that lies at rest opposite the velum or the back part of the palate.

(III) A.L. Trakhterov, G.P. Torsyev, V.A. Vassilyev and other Russian scholars consider the

principle of classification according to the manner of articulation to be one of the most important

and classify consonants very accurately, logically and thoroughly. They suggest a classification

from the point of view of the closure. It may be: (1) complete closure, then occlusive (stop or

plosive) consonants are produced; (2) incomplete closure, then constrictive consonants are

produced; (3) the combination of the two closures, then occlusive- constrictive consonants, or

affricates, are produced; (4) intermittent closure, then rolled, or trilled consonants are produced.

(IV) According to the position of the soft palate all consonants are subdivided into oral and

nasal. When the soft palate is raised oral consonants are produced; when the soft palate is

lowered nasal consonants are produced.

(V) According to the force of articulation consonants may be fortis and lenis. This

characteristic is connected with the work of the vocal cords: voiceless consonants are strong and

voiced are weak.

C. are classified according to the main principles:

To the type of obstruction

Occlusive – produce with the complete obstruction to the air stream they may be noise (plosives)

[p, b, t, k, g] and affricates and sonorants [m, n, ŋ]

Constructive – produced with an incomplete obstruction and may be noise or fricatives [v, f, s, z,

h, g] and sonorant median [w,, r, j] and lateral one [l]. In pronunciation of which the air passage

is rather wide, the air passing through the mouth doesn’t produce audible friction and tone

prevails over noise.

To the manner of production the noise

Plosives – the organs of speech form a complete obstruction, which is than quickly released with

plosion [p, b, t, d, k, g]

Affricates – the speech organs forms a complete obstruction, which is than released so slowly,

that considerable friction accursed at the point of articulation [ch, dz]

Fricatives - the speech organs forms a incomplete obstruction and the air passes producing

audible friction [b, f, ð, Ө, s, z, h, g]

Sonorance: 1)occlusive the speech organs forms a complete obstruction, which is not released.

The soft palate is lowed and the air escapes through the nasal cavity [m, n, ŋ]

2) constrictive: a) median – the air escapes without audible friction over the central part of the

tongue the sides of the tongue being raised [w, r, j]

b) lateral – the tongue is pressed against the alveolar ridge or the teeth and the sides of the tongue

are lowed, leaving the air passage open between tem [l].

To the active organs of speech

Labial – 1) bilabial - articulated by the 2 lips [p,b]

2) labial-dental – articulated with the low lip, against the upper teeth [v,f]

Lingual – 1) fore lingual – articulated by the blade of the tip or by the tip against the upper teeth

or alveolar ridge: a) apical [ð, Ө, t, d, l, n, s, z] b) cacuminal [r]

2) medium lingual –articulated with the front of the tongue against the hard palate [j]

3) back lingual – articulated by the front of the tongue against the soft palate. [k, g, ŋ]

Glottal – produced in the glottis [h]

To the point of articulation

Dental

Alveolar

Palatal-alveolar

Post-alveolar

Palatal

Velar

To the work of the vocal cords

Voiced

Voiceless

To the force of articulation

Relatively strong (forties)

Relatively weak (lenis)

English voiced care lenis, English voiceless are forties

The first who tried to describe and classify vowels irrespective of the mother tongue was Daniel

Johnes. He worked out a system of 8 cardinal vowels. This system is an international standard

which presents a set of artificial vowels and which contains all the vowel types existing in

different languages of the world. In reference to this system the vowel sounds of any real

language of the world may be described and classified and sometimes this system is called the

vocalic Esperanto.

FrontBack

close i u

half-close e o

half-open ə ɔ

open a ɑ

The tongue can move horizontally and vertically and according to these movements Daniel

Johnes represented his 8 cardinal vowels. The system of cardinal vowels has a great theoretical

value and it is used as a basis for classification of vowels in different languages.

Russian phoneticians suggest classifying vowels according to the following principle: 1) position

of the lips; 2) position of the tongue; 3) degree of tenseness; 4) length; 5) stability of articulation.

1) position of the lips. According to this principle vowels are classified into rounded [ɔ, ɔ:, u,

u:]and unrounded.

2) Position of the tongue. The bulk of the tongue conditions the production of different vowels

most of all its horizontal and vertical movement forms vowels of a particular language.

According to the horizontal movement English vowels are classified into the following groups:

1) front vowels [i:, e, æ], nucleus of the diphthongs[eɪ, ɑɪ, ɛə]; 2) front retracted [ɪ], nucleus of

the diphthong [ɪə]; 3) mixed vowels [ə, ə:], the term mixed is used by the Russian phoneticians

because in the production of this group of vowels the tongue is raised towards the junctions

between the soft and hard palates. British phoneticians call these vowels central, because the

central part of the tongue is raised highest in their pronunciation; 4) back advanced [u,ɔ, ʌ], the

nucleus of the diphthongs [əʊ, ʊə]; 5) back vowels , [u:,ɔ:,ɑ], diphthongs [ɔɪ, ɛə].

According to the vertical movement of the tongue English vowels have been traditionally

subdivided into 3 groups: 1) high (close) vowels [ɪ,i:,u,u:]; 2) mid-vowels [e,ə,ə:,a], nucleus of

[əu,ɛə]; 3) low (open) vowels [ʌ, ɔ, ɔ:, ɑ:], nucleus [aɪ, au].

3) The degree of muscular tension. Classified into tense and lax.All long vowels are tense,

short vowels are lax.

4) Length of vowels. English vowels are historically subdivided into long and short. Vowels

length depends on a number of linguistic factors. Firstly, position of the vowel in a word [si: si:d – si:t] - [si: - si· – si]. For the voiceless consonants the length of a long vowel is the shortest.

Word accent. In the stressed syllable the vowel has the maximum length. 'forecast [ɔ:], fore'cast

[ ɔ·,ɑ:]. The number of syllables in a word, e.g. verse, university. In a mono-syllabic word the

vowel is longer, than in a poly-syllabic one. The character of the syllabic structure. In the words

with open types of syllable vowels are longer than in words with closed types.

Articulatory transitions of vowel and cons phonemes.

In the process of speech, that is in the process of transition from the articulatory work of one

sound to the articulatory work of the neighbouring one, sounds are modified. These

modifications can be conditioned:

a) by the complementary distribution of phonemes, e. g. the fully back /u:/ becomes backadvanced under the influence of the preceding mediolingual sonorant /j/ in the words tune,

nude. In the word keen /k/ is not so back as its principal variant, it is advanced under (be

influence of the fully front /i;/ which follows it:

b) by the contextual variations in which phonemes may occur at the junction of words, e. g. the

alveolar phoneme /n/ in the combination in the is assimilated to the dental variant under the

influence of /ð/ which follows it;

c) by the style of speech: official or rapid colloquial. E. g. hot muffins

may turn into

Assimilation is a modification of a consonant under the influence of a neighbouring consonant.

When a consonant is modified under the influence of an adjacent vowel or vice versa this

phenomenon is called adaptation or accommodation, e. g. tune, keen, lea, cool.

When one of the neighbouring sounds is not realized in rapid or careless speech this process is

called elision, e. g. a box of matches may be pronounced without [v].

Assimilation which occurs in everyday speech in the present-day pronunciation is called living.

Assimilation which took place at an earlier stage in the history of the language is called

historical.

Assimilation can be:

1progressive, when the first of the two sounds affected by assimilation makes the second sound

similar to itself, e. g. in desks the sounds /k/ make the plural inflection s similar to the voiceless

/k/.

2regressive, when the second of the two sounds affected by assimilation makes the first sound

similar to itself, e. g. in the combination at the the alveolar /t/ becomes dental, assimilated to the

interdental / ð / which follows it;

3double, when the two adjacent sounds influence each other, e.g. twice /t/ is rounded under the

influence of /w/ and /w/ is partly devoiced under (he influence of the voiceless /t/.

When the two neighbouring sounds arc affected by assimilation, it may influence: 1) the work of

the vocal cords; 2) the active organ of speech; 3) the manner of noise production; 4) both: the

place of articulation and the manner of noise production.

l)Assimilation affecting the work of the vocal cords is observed when one of the two adjacent

соседний consonants; becomes voiced under the influence of the neighbouring voiced

consonant, or voiceless — under the influence of the neighbouring voiceless consonant.

In the process of speech the sonorants /m, n, 1, r; j, w/ are partly devoiced before a vowel,

preceded by the voiceless consonant phonemes /s, p, t, k/, e. g. plate, slowly, twice, ay. This

assimilation is not observed in the most careful styles of speech.

2) The manner of noise production is affected by assimilation in cases of a) lateral plosion and b)

loss of plosion or incomplete plosion. The lateral plosion takes place, when a plosive is followed

by /1/. In this case the closure for the plosive is not released till the off-glide for the second

[l]. Incomplete plosion takes place in the clusters a) of two similar plosives like /pp,pb, tt, td, kk,

kg/, or b) of two plosives with different points of articulation like:/kt/,/dg/, /db/, /tb/. So there is

only one explosion for the two plosives.

+3) Assimilation affects the place of articulation and the manner of noise production when the

plosive, alveolar /tl is followed by the post-alveolar /r/. For example, in the

word trip alveolar 1t1 becomes post-alveolar and has a fricative release.

7. The system of phonological oppositions in English.

Minimal pairs are useful for establishing the phonemes of the language. Thus, a phoneme can

only perform its distinctive function if it is opposed to another phoneme in the same position.

Such an opposition is called phonological. Let us consider the classification of phonological

oppositions worked out by N.S. Trubetskoy. It is based on the number of distinctive articulatory

features underlying the opposition.

1. If the opposition is based on a single difference in the articulation of two speech sounds, it is a

single phonological opposition, e.g. [p] – [t], as in [pen]-[ten]; bilabial vs. forelingual, all the

other features are the same.

2. If the sounds in distinctive opposition have two differences in their articulation, the opposition

is double one, or a sum of two single oppositions, e.g. [p] – [d], as in [pen] – [den], 1) bilabial vs.

forelingual 2) voiceless – fortis vs. voiced – lenis.

3. If there are three articulatory differences, the opposition is triple one, or a sum of three single

oppositions, e.g. [p] – [ð], as in [p‡] – [ ð‡]: 1) bilabial vs. forelingual, 2) occlusive vs.

constrictive, 3) voiceless – fortis vs. voiced – lenis.

Classificatory principles of English vowel and consonant phonemes provide the basis for

establishing the distinctive oppositions.

Distinctive oppositions of English

consonants

Classificatory principles and

subclasses of phonemes

1. Work of the vocal cords: voiced [b, d, g, v, z, ð,3, d3, l, m,

n, j, w, r, ŋ]; - voiceless [p, t, k, f,

s, θ, ∫, t∫, h].

Types of oppositions

Examples

voiced – voiceless The

English consonants [l, m, n, j,

w, r, ŋ, h] do not enter this

opposition.

gum – come dear –

tear bat – pat jin –

chin thy – thigh

2. Position of the soft palate: nasal [m, n, ŋ]; - oral (all the rest).

3. Active organ of speech and the

place of articulation: a) labial: bilabial [p, b, w, m]; - labio-dental

[f, v]; b) lingual: - forelingual [ð,

θ, t, d, s, z, n, l, ∫, 3, d3, t∫]; mediolingual [j]; - backlingual [k,

g, ŋ]; c) glottal [h].

4. Manner of the production of

noise: a) occlusive: - plosive [p, t,

k, b, d, g] - sonorant [m, n, ŋ]; b)

constrictive: - fricative [s, f, z, ð, θ,

∫, v,3, h]; - sonorant [w, r, j, l]; c)

occlusive-constrictive (affricates)

[t∫, d3].

Distinctive oppositions of English

vowels

Classificatory principles and

subclasses of phonemes

1. Position of the lips: - rounded

[o, o:, u, u:]; - unrounded (all the

rest).

2. Stability of articulation: monophthongs [i, i:, u, u:, o, o:, e,

ə, Λ, α:, æ, з:]; - diphthongs [ai, oi,

ei, au, əu, εə, uə, iə].

3. Degree of tenseness, character

of the end and length: - tense, free

and long [i:, u:, o:, α:, з:]; - lax,

checked and short [i, u, o, æ, e, ə,

Λ].

4. Position of the tongue: a)

horizontal: - front [i:, e, æ]; - frontretracted [i]; - central [з:, ə, Λ]; back-advanced [u, α:]; - back [o,

o:, u:]; b) vertical: – high: - narrow

[i:, u:]; - broad [i, u]; – mid: narrow [ə]; - broad [e, o:, з:]; –

low: - narrow [Λ]; - broad [æ, α:,

o:].

oral – nasal

labial – lingual lingual –

glottal labial – glottal bilabial –

labio-dental forelingual –

mediolingual forelingual –

backlingual mediolingual –

backlingual

pit – pin seek – seen

sick – sing

pain – cane this –

hiss foam – home

wear – fair jet – yet

thing – king yes –

guess

occlusive – constrictive

affricate – constrictive affricate

– occlusive occlusive: plosive –

sonorant constrictive: fricative

– sonorant

bat – that fair –

chair chin – pin pine –

mine same – lame

Types of oppositions

Examples

rounded – unrounded

monophthong – diphthong

tense lax free — checked

long short

front – central back – central

front – back front – frontretracted back – backadvanced high – mid low –

mid high – low high narrow –

high broad mid narrow – mid

broad low narrow – low broad

pot – pat

bit – bait but – bite

debt – doubt bird –

beard

peel – pill

cab – curb pull –

pearl read – rod bet –

bit card – cord week

– work lack – lurk big

– bag pool – pull

foreword – forward

bad – bard

8. Phoneme and allophone. Types of allophones.

First of all, the phoneme is a minimal abstract linguistic unit realized in speech in the form of

speech sounds opposable to other phonemes of the same language to distinguish the meaning of

morphemes and words (L.V. Shcherba).

Oral realization of the phoneme called allophone. For example let, talk, try, stay,

This aspect is reflected in this part of the definition: “realized in speech in the form of

speech sounds”. In other words, each phoneme is realized as a set of predictable speech sounds,

which are called allophones.

Allophones of the same phoneme generally meet the following requirements:

1. they possess similar articulatory features, but at the same time they may show

considerable phonetic differences;

2. they never occur in the same phonetic context

3. they can’t be opposed to one another, they are not able to differentiate the meaning.

The difference between allophones is the result of the influence of the neighbouring

sounds, or the phonetic context. We distinguish two types of allophones; principal and

subsidiary. The allophones which don’t undergo any changes in the chain of speech are called

principal. They are closest to the sound pronounced in isolation. In the articulation of

subsidiary allophones we observe predictable changes under the influence of the phonetic

context.

The actually pronounced sound that we hear reflects phonostylistic, regional, occasional

and individual peculiarities, it is called the phone.

The behavior of allophones in phonetic context, their ability to occur in certain definite positions

– distribution.

There are 3 types of distribution:

1. constrastive/parallel/overlapping – in this position these types of distribution are

typical: [n] – [ŋ]

2. complementary – allophones of one and the same phoneme. Never in the same position:

[k] – [k] (aspirated – non-aspirated).

3. free variation – allophones of one and the same phoneme that allocate in the same

position. They aren’t able to differentiate the meaning: Good night with glottal stop and

without it.

Functions of phoneme:

1. constituetive – phoneme constitutes words, word combinations etc. Phonemes have no

meaning of their own, linguistically important for in the material form of their allophones

they serve as a building material for words and morphemes;

2. distinctive – phonemes help to distinguish the meanings of words, morphemes;

3. identificatory (recognitive) – phoneme makes up gr-l forms of words, sentences, so the

right use of allophones.

Some phonologists single out delimiting function.

The function of phonemes is to distinguish the meaning of morphemes and words. So the

phoneme is an abstract linguistic unit, it is an abstraction from actual speech sounds, that is

allophonic modifications.

THEORY OF GRAMMAR

9. General characteristics of MnE structure.

The English language is said to be more analytical than synthetical or “mainly” analytical. The

choice of word-order is seldom relevant gram. in Russian, it is only relevant stylistically.

Modern English has comparatively few gram. inflexions it is characterized by a certain

“scarcily” or “poverty” of inflexions and in a great number of cases by the absence of synthetic

forms of word-changing. There are two different ways of inflexion: synthetic (affixation,

morphophonemic alternation, supplexion) and analytical.

The word order plays a very important role in expressing gram. relations in an English sentence.

It is fixed to a greater degree than in inflected language.

The rigid word order and scarcity of inflexion result in a very peculiar English sentence

structure: it tends to be completed. Hence, the use of a special set of words employed as

structural substitutes (prop-words) for a certain part of speech: the noun substitutes (one, that),

the verb substitutes (do, to), the adverb and adjective substitutes (so).

Practically any word or a group of words preceding the head-word is automatically felt to be

attributive, i.e. it becomes its attribute, its premodifier (films festivals).

The tendency towards heavy premodification, i.e. the use of complex group premodifiers, i.e.

spreading in English (round-the-clock service).

To revoid the repetition of the head word in a phrase, we use a substitute word. Thus preserving

a usual structure and completeness of an English sentence (She is a teacher and a good one).

Possessing such a poorly developed system of word changing, Modern English widely uses

function words for connecting words and phrases and for expressing various grammatical

meanings of words and their syntactic functions in the sentence.

Function words include prepositions, conjunctions, articles. Their role in expressing syntactical

relations in Modern English can hardly be overestimated, without function words the English

language wouldn’t simply work. The status of function words is to a certain extent contradictory:

being words by the form, by their function they belong to the grammatical structure.

Though the number of function words is very limited, they enjoy the high frequency of

occurrence, especially the article “the”, the conjunction “and” and the preposition “of”.

Among the distinctive features characterizing Modern English we should also point out the

existence of the so-called secondary or potential predication, resulting in rapid spread and

wide use of predicate complexes or constructions, which are directly related to certain types of

subordinate clauses.

The predicative complex, including a nominal and a verbal components, is not self-dependent in

a predicative sense. It normally exists only as a part of a sentence, which is built up by means of

a primary predicative constructions that has a finite verb as its backbone.

Some foreign linguists, mainly those, who shared the reactionary theory of the supremacy of one

language over another tried to make people believe that such phenomena as “heavy

premodification” or “secondary predication” directly reflected racial and political supremacy of

the English nation. O. Jespersen, being a Dane himself and a prominent anglicist, was an ardent

admirer of the English language. In his book “Growth and Structure of the English Language” he

wrote: “Although such combinations as the last mentioned are only found in more or less jocular

style, they show the possibilities of the language, and some expressions of a similar order belong

permanently to the language…Such things – and they might be easily multiplied – are

inconceivable in such a language as French, where everything is condemned that does not

conform to a definite set of rules laid down by grammarians. The French language is like the stiff

French garden of Louis XIV, while the English language is like an English park, which is laid

out seemingly without any definite plan (order), and in which you are allowed to walk

everywhere according to your own fancy without having to fear a stern keeper enforcing

rigorous regulations. The English language would not have been what it is if the English had not

been for centuries great respecters of the liberties of each individual and if everybody had not

been free to strike out new paths for himself”.

10. The English noun, its semantic and grammatical peculiarities.

The noun is the central lexical unit of language. It is the main nominative unit of speech. As any

other part of speech, the noun can be characterised by three criteria: semantic (the meaning),

morphological (the form and grammatical catrgories) and syntactical (functions, distribution).

The noun denotes substance or thingness. It is considered to be the main nominative part of the

speech. Nouns name things, living creatures, qualities, places, materials, states, abstract notions.

The noun has the power by way of nomination, to isolate different properties of substances and

present them as corresponding self-depended substances. Practically any part of speech can be

substantivized.

Semantic features of the noun. The noun possesses the grammatical meaning of thingness,

substantiality. According to different principles of classification nouns fall into several

subclasses:

1.

According to the type of nomination they may be proper and common;

2.

According to the form of existence they may be animate and inanimate. Animate nouns in

their turn fall into human and non-human.

3.

According to their quantitative structure nouns can be countable and uncountable.

This set of subclasses cannot be put together into one table because of the different principles of

classification.

Semantically nouns fall into proper and common. Common nouns are subdivided into count and

non-count. The former are inflected for number where the latter are not. Further distinction is

into concrete, abstract and material.

Concrete

Countable

Abstract

Common

Nouns

Non-countable

Material

Proper

Abstract

Concrete nouns fall into three subclasses:

1. Nouns denoting animate beings (living beings) – persons and animals.

2. Nouns denoting inanimate objects.

3. Collective nouns denoting a group of persons. These may be further subdivided into:

a) collective nouns proper denoting both a group consisting of separate individuals

and at the same time considered as a single body.

e.g. The family were on friendly but guarded terms.

Our family is neither large nor small.

b) nouns of multitude which are always associated with the idea of plurality, they

denote a group of separate individuals: police, clergy, cattle, etc.

e.g. The police here are efficient.

According to their morphological composition nouns can be divided into simple, derived,

compound.

Simple nouns consist of only one root-morpheme: dog, chair, room, roof, tree, etc.

Derived nouns are composed of one root-morpheme and one or more derivational morphemes

(prefixes or suffixes). The main noun-forming suffixes are those building up abstract nouns and

those building up concrete, personal nouns.

The categorial functional properties of the noun are determined by its semantic properties. The

most characteristic substantive functions of the noun are those of the subject and the object.

Other syntactic functions – attributive, adverbial, predicative – are not immediately characteristic

of the substantive quality of the noun. It is to be noted that, while performing these nonsubstantive functions, the noun essentially differs from other parts of speech used in similar

sentence positions. This may be clearly shown by transformations shifting the noun from various

non-subject syntactic positions into subject syntactic positions of the same general semantic

value, which is impossible with other parts of speech.

Besides countability, nouns can be described by four other important grammatical

characteristics: gender, number, person, and case. These grammatical characteristics are

reflected in the choice of pronouns, the choice of number endings on the noun (singular or

plural), and the choice of subject-verb agreement endings when the noun is a subject.

Gender plays a relatively minor part in the grammar of English by comparison with its role in

many other languages. There is no gender concord, and the reference of the pronouns he, she, it

is very largely determined by what is sometimes referred to as ‘natural’ gender for English, it

depends upon the classification of persons and objects as male, female or inanimate. Thus, the

recognition of gender as a grammatical category is logically independent of any particular

semantic association.

Case expresses the relation of a word to another word in the word-group or sentence (my sister’s

coat). The category of case correlates with the objective category of possession. The case

category in English is realized through the opposition: The Common Case: The Possessive Case

(sister – sister’s). However, in modern linguistics the term “genitive case” is used instead of the

“possessive case” because the meanings rendered by the “`s” sign are not only those of

possession. The scope of meanings rendered by the Genitive Case is the following:

1.

Possessive Genitive : Mary’s father – Mary has a father,

2.

Subjective Genitive: The doctor’s arrival – The doctor has arrived,

3.

Objective Genitive : The man’s release – The man was released,

4.