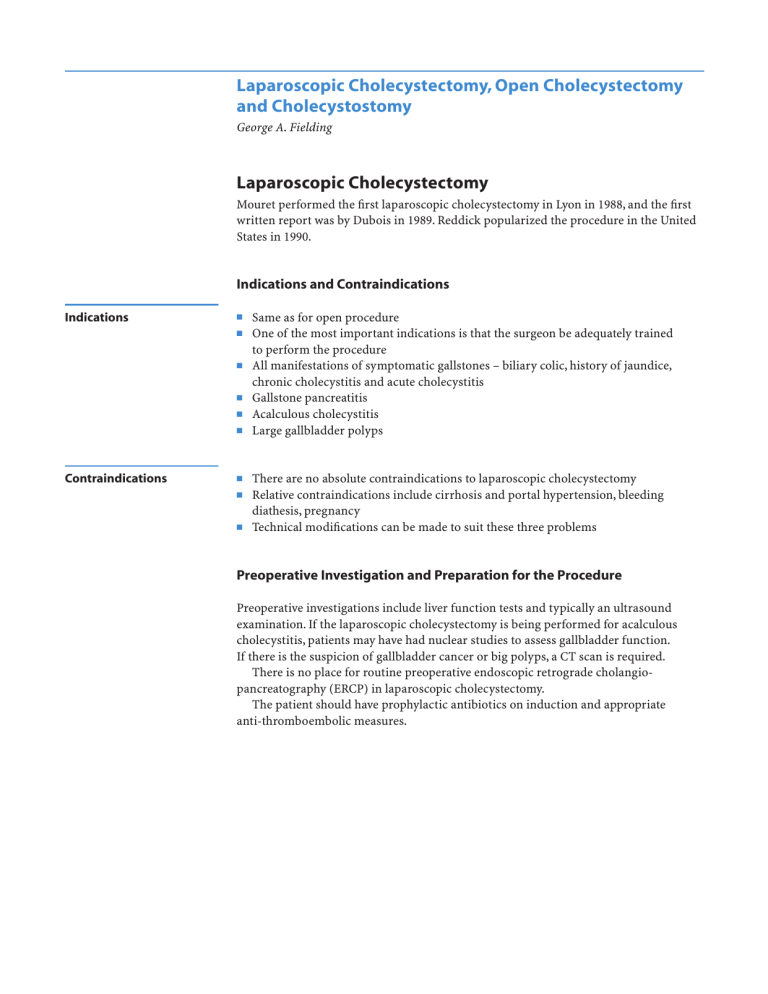

Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy, Open Cholecystectomy and Cholecystostomy George A. Fielding Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy Mouret performed the first laparoscopic cholecystectomy in Lyon in 1988, and the first written report was by Dubois in 1989. Reddick popularized the procedure in the United States in 1990. Indications and Contraindications Indications ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Contraindications ■ ■ ■ Same as for open procedure One of the most important indications is that the surgeon be adequately trained to perform the procedure All manifestations of symptomatic gallstones – biliary colic, history of jaundice, chronic cholecystitis and acute cholecystitis Gallstone pancreatitis Acalculous cholecystitis Large gallbladder polyps There are no absolute contraindications to laparoscopic cholecystectomy Relative contraindications include cirrhosis and portal hypertension, bleeding diathesis, pregnancy Technical modifications can be made to suit these three problems Preoperative Investigation and Preparation for the Procedure Preoperative investigations include liver function tests and typically an ultrasound examination. If the laparoscopic cholecystectomy is being performed for acalculous cholecystitis, patients may have had nuclear studies to assess gallbladder function. If there is the suspicion of gallbladder cancer or big polyps, a CT scan is required. There is no place for routine preoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The patient should have prophylactic antibiotics on induction and appropriate anti-thromboembolic measures. 528 SECTION 4 Biliary Tract and Gallbladder Procedure STEP 1 Access The procedure should be performed on a table allowing operative cholangiography. There is no routine need for a nasogastric tube or Foley catheter. Typically there is no requirement for invasive anesthetic monitoring. Patients are placed supine, legs together with a slight reverse Trendelenburg position. There is little to gain by using a steep reverse Trendelenburg position. Safe access: Open insertion of a Hasson cannula through a transumbilical incision. Eversion of the umbilicus creates access via the gap in the linea alba at the base of the umbilicus. The Hasson cannula can be sat directly in the peritoneal cavity. There is no need for stay sutures nor to suture the port in place. A 30° telescope is used; insufflation pressures are set at 15mmHg. Placement of other access parts is as shown in the figure. Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy, Open Cholecystectomy and Cholecystostomy STEP 2 529 Retraction and dissection of Calot’s triangle Once caudad retraction of the fundus is established, the crucial maneuver is lateral retraction of Hartmann’s pouch by the upper lateral 5-mm port. This places Calot’s triangle on the stretch and will greatly reduce the chance of injury of the common bile duct. STEP 3 Then incise the posterior peritoneal attachment behind Hartmann’s pouch to separate Hartmann’s pouch from the liver to further stretch out Calot’s triangle. 530 SECTION 4 Biliary Tract and Gallbladder STEP 4 Once these two maneuvers are instituted, hook dissection can be performed, staying close to the gallbladder to incise the anterior sheet of peritoneum over Calot’s triangle. This will expose one or two cystic arteries and the cystic duct . Windows should be developed between all these structures before anything is divided. Once the anatomy is determined (see anatomical variations and tricks), the cystic arteries are divided between clips and a clip is placed below Hartmann’s pouch to the proximal end of the cystic duct. Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy, Open Cholecystectomy and Cholecystostomy STEP 5 Cholangiography Lateral retraction of Hartmann’s pouch is maintained by a grasper, this time coming from the subxiphoid port. The cystic duct is incised through the right (A). The cystic valve can occasionally make this difficult. A No.4 ureteric catheter with an end hole is inserted through the Olsen-Reddick cholangiogram clamp into the cystic duct and the clamp closed around the duct (B). Operative cholangiography is then performed with aid of C-arm fluoroscopy. Cholangiography confirms the biliary anatomy and reveals the common duct stones, allowing laparoscopic duct exploration. 531 532 SECTION 4 STEP 6 Removal of gallbladder Biliary Tract and Gallbladder Once cholangiography is completed, the ureteric catheter is removed and the cystic duct is clamped. The gallbladder is then removed from the liver bed using hook diathermy. This is done through a combination of elevating the peritoneum, burning with the hook and pushing so that the gallbladder is removed toward the fundus and finally separated from the liver at the fundus. There is very little place for fundus-first laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy, Open Cholecystectomy and Cholecystostomy 533 Anatomical Variations ■ ■ ■ The major anatomical variations are involved with the common bile duct and the right hepatic artery. A very small common bile duct can be mistaken for the cystic duct and completely excised. Even more worrisome is the variant of a low junction of the left and right hepatic ducts (A) or a low junction of the right anterior and right posterior hepatic ducts (B). In these situations the cystic duct can enter the right hepatic duct or the right posterior hepatic duct. The right or right posterior ducts can therefore be mistaken for the cystic duct and divided. More rarely, but even more difficult, particularly in the setting of acute cholecystitis, is when there is no cystic duct and Hartmann’s pouch opens directly underneath the right hepatic duct or the common duct. 534 SECTION 4 Biliary Tract and Gallbladder Complications Bleeding The major intraoperative complication is bleeding. This is typically from a very short cystic artery or from the right hepatic artery itself. Bleeding from the portal vein is very rare, but in contrast to hepatic and cystic artery bleeding, it is always torrential and the patient must be opened. Failure to Progress The second major complication is failure to progress. If the surgeon is not making any progress, the patient should be converted to an open cholecystectomy. Bile Duct Injury Proper retraction, careful dissection, steady control of hemorrhage and recognition of an appropriate time to convert to open cholecystectomy should minimize the chance of the most feared intraoperative complication – bile duct injury or bile duct resection. If a duct injury is recognized the surgeon should just stop, collect his or her thoughts, and ring a hepatobiliary colleague immediately. Postoperative Complications ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Most bile leaks are low volume and will settle spontaneously. A high volume bile leak is suggestive that the clip has come off the cystic duct or there is a major unrecognized duct injury. ERCP will determine this, allowing appropriate management. Subphrenic collection may require percutaneous drainage. Pneumonia – best treated with physiotherapy and antibiotics. Jaundice suggests major duct obstruction or excision – ERCP or referral to a hepatobiliary specialist. Tricks of the Senior Surgeon ■ ■ ■ In cases with portal hypertension and cirrhosis, patients should be considered for a partial cholecystectomy, where the back wall of the gallbladder is left on the liver bed. Failure to do so can result in life-threatening hemorrhage. Furthermore, with laparoscopic surgery, you simply will not be able to see the operative field due to the blood. In severe acute cholecystitis, the first step is to decompress the gallbladder by inserting the trocar directly into the gallbladder and aspirating the contents. This will convert a tense, unmanageable gallbladder to a collapsed thick-walled gallbladder that can be grasped and maneuvered. If there is a stone impacted in Hartmann’s pouch, it should be pushed back into the gallbladder to allow safe manipulation of Calot’s triangle. Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy, Open Cholecystectomy and Cholecystostomy 535 Open Cholecystectomy Until 1989 open cholecystectomy was the procedure of choice for all the complications of symptomatic gallstones. It has largely been supplanted by laparoscopic cholecystectomy as a freestanding elective procedure. The principle of open cholecystectomy is removal of the gallbladder and its contents with preservation of the biliary tree. Indications and Contraindications Indications ■ ■ ■ ■ Contraindications ■ ■ Failed laparoscopic cholecystectomy Whipple resection or bile duct resection as part of hepatectomy Patient choice Suspected malignant gallbladder polyp There are no absolute contraindications to cholecystectomy A severely ill patient where a cholecystostomy may be the best option Open cholecystectomy is now performed most frequently as part of other major procedures as listed above. If it is in the setting of a failed laparoscopic procedure it is often a very difficult cholecystectomy and it is vital in this situation to make an adequate incision. Preoperative Investigation and Preparation for the Procedure ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Liver function tests Ultrasound Planning of associated major procedure Clinical preparation and prophylactic antibiotics Anti–deep vein thrombosis therapy of choice 536 SECTION 4 Biliary Tract and Gallbladder Procedure STEP 1 Positioning and incision Operative table allowing C-arm fluoroscopy. If done for patient choice, and there are no other contraindications, a 5-cm transverse incision is centered over the lateral border of the rectus sheath made. STEP 2 After conversion from laparoscopic cholecystectomy, it is essential to make an adequate incision, as the main reason for conversion is an anatomical difficulty usually in the setting of an inflamed gallbladder. A long right subcostal incision is made a finger´s width below the costal margin. The rectus sheath is divided in the line of the incision and this is taken down to the peritoneum using diathermy coagulation. Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy, Open Cholecystectomy and Cholecystostomy STEP 3 The peritoneal cavity is elevated with the fingers and the wound incised along its full length. Three packs are inserted – one behind the liver, one on the colon and one over the gastroduodenal area and retractors are placed over the gastroduodenal area and one over the liver to place Calot’s triangle on the stretch. 537 538 SECTION 4 Biliary Tract and Gallbladder STEP 4 The key step in open cholecystectomy is division of the cystic artery, which allows Hartmann’s pouch to swing out and allow clear definition of the biliary anatomy. The cystic duct is clipped and the gallbladder is retracted inferiorly and dissected free of the liver. Cholangiography is typically performed through the cystic duct using the same equipment as for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Once the anatomy has been determined and cleared, the gallbladder is removed. This is typically done starting from Hartmann’s pouch, but in the case of severe inflammation it may be better done with the fundus first dissection, carefully dividing in the plane between the liver and the gallbladder (A-1, A-2). A-1 A-2 Complications These complications are the same as those for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy, Open Cholecystectomy and Cholecystostomy 539 Cholecystostomy Indications and Contraindications Indications ■ ■ Percutaneous cholecystostomy is used most commonly in the setting of a severely ill patient with underlying gallbladder sepsis. Operative severe inflammation of Calot’s triangle at surgery where the safest option is to decompress the gallbladder. Procedure Cholecystostomy may be performed open but this is much more typically found at laparoscopic cholecystectomy. STEP 1 The 5-mm lateral trocar is inserted directly into the gallbladder and the gallbladder aspirated. The gallbladder will collapse, typically showing a large stone in Hartmann’s pouch; if this can be milked back and removed it should be done. STEP 2 A Foley catheter is inserted via the lateral port directly into the gallbladder. Cholangiography can be completed via this if indicated. STEP 3 The trocar is removed from the gallbladder, leaving the Foley catheter in place, which is then insufflated. The gallbladder is sutured 2nd request around the Foley catheter. The Foley catheter is then left on free drainage and should be left in place at least 6weeks to allow the gallbladder to settle prior to returning to complete the laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The Foley catheter should be irrigated twice daily with 20ml of saline.