English Studies at NBU

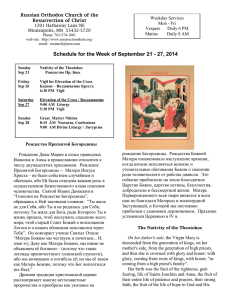

реклама